“Our ability to access endowment wealth has enabled us to move forward” on priorities such as the new science complex in Allston, renovation of the Fogg Art Museum, and financial aid for lower- and middle-income families. So said acting chief financial officer Daniel S. Shore, reviewing fiscal year 2008 (ended last June 30), as detailed in the Harvard University Financial Report, released in October (available on line at https://vpf-web.harvard.edu/annualfinancial). His assessment neatly summarized Harvard’s fiscal position, aims, and challenges.

Fueled above all by distributions from the endowment (valued at $36.9 billion at fiscal year-end; see “Endowment Edges Up in a Down Year,” page 60), revenue rose 8.4 percent to $3.48 billion and expenses increased 9.3 percent to $3.46 billion—rates of growth faster than in the prior fiscal year. The University achieved a modest operating surplus even as it pursued significant programmatic and physical expansion. But given recent chaos in the financial markets, rising reliance on income from the endowment to fund operations raises questions about future budgets—particularly, Shore said, “in an environment where the ability to get sponsored-research funding from the federal government continues to be challenging.”

A few line items in the report merit examination. Federal sponsored funding rose about 4 percent, to $535 million, with National Institutes of Health funding up less than 2 percent. That was better than the worrisome decline in fiscal year 2007, but did not keep pace with either the inflation in research costs nor the larger population of scientists seeking funds. Shore said the slight improvement likely reflected no trend: “Up 2 percent in nominal terms is nothing to jump up and down about.”

Among Harvard’s expenses—up a brisk $294 million—compensation costs, the largest single category, rose 7 percent, reflecting an 8 percent increase in salaries and wages (driven, Shore said, by both pay increases and workforce expansion), and a 6 percent growth in benefits (relatively favorable compared to recent experience). The allocation of expenses between the University and the Broad Institute (a genomics-research joint venture with MIT, which will become a freestanding nonprofit organization in the next year or two), and between Harvard and an affiliated hospital, increased expenses more than $40 million in fiscal year 2008 compared to the prior year; that ought to be seen as a short-term, largely nonrecurring swing, according to Sharon D. DeMaranville, director of financial reporting. Travel expenses rose 18 percent, in line with a recent trend, as the University continues to “expand our footprint internationally,” Shore said.

Capital spending declined fractionally, to $591.1 million, reflecting completion of work on graduate-student-housing projects, large new lab buildings, and other Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) projects. But, Shore said, “We certainly expect to see more,” given academic aspirations and work already under way: the Allston science complex, Harvard Law School’s office and classroom building (see March-April, page 54), and the Fogg renovation—three projects expected to cost perhaps $1.7 billion in all—and such planned work as the renovation of the undergraduate Houses.

Harvard continues to fund such capital programs with debt: bonds and notes payable totaled $4.1 billion on June 30, up from $3.8 billion on June 30, 2007 (during which fiscal year debt outstanding rose by more than $900 million). In the normal course of events, Shore said, Harvard’s net borrowings will continue to rise, in keeping with the capital plan.

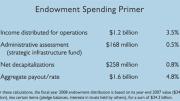

Endowment income distributed for operations rose nearly $158 million, or 15 percent, to just above $1.2 billion (see table). The administrative assessment that allows the University to contribute to the “strategic infrastructure fund” (Allston development expenses) rose $28 million, or nearly 20 percent, to $168.4 million. And unspecified “decapitalizations” for one-time or time-limited purposes totaled $258.2 million; in fiscal year 2007, a $100-million decapitalization in support of FAS construction was identified.

The fiscal year 2008 “distribution rate” established by the Corporation for all eligible funds amounted to 4.1 percent of the endowment’s year-end 2007 value, down from 4.3 percent. (Endowment investment returns were an extraordinary 23 percent in fiscal year 2007; such gains lower the distribution rate even when the dollars distributed for operations rise significantly, as occurred this past year.) Summing all endowment funds tapped—$1.6 billion, including the decapitalizations of principal—the “aggregate payout rate” came to 4.8 percent, up from 4.6 percent in 2007. Those figures all slightly trail the Corporation’s goal of a 5.0 to 5.5 percent aggregate payout rate—the level commonly bruited about in congressional discussions of appropriate spending from tax-exempt private university endowments. (See “Endowments—Under a Tax?” July-August, page 65; the most recent hearing on the issue took place in the U.S. Senate on September 8; see Brevia, page 71.)

But spending less in fiscal year 2008 than the longer-term goal for endowment use may be prudent. A sustained, sharp decline in the value of financial and other assets could trim the size of the endowment itself, even as demands upon it grow. And there are other concerns. As in recent years, the “Annual Report of the Harvard Management Company,” within the University Report, mentions that “as HMC deepens and widens its relationships with external managers, efforts are being made to counteract the existing market tendency towards a lower level of information transparency.” The HMC report discloses that HMC’s private-equity portfolio consisted of 210 separate funds managed by 80 different external firms.

In fact, Shore and DeMaranville noted, HMC kept its books open longer this year than last to work with external money-management firms on the asset values they reported. Being confident that those often-illiquid investments are properly valued, in volatile markets, will matter even more in fiscal year 2009 and beyond, because the University’s reporting came under Financial Accounting Standards No. 157, Fair Value Measurements, as of July 1, and so will henceforth have to satisfy itself, and its auditors, that asset measurements do indeed reflect fair value.

As the Corporation determines, in late fall or early winter, the level of endowment spending and the budget for fiscal year 2010, Shore said, “It’s hard to have any crystal-ball conversation not shadowed by the environment.” From his perspective, University operations are proceeding well. The financial-aid initiatives, for example, increased the pool of undergraduate and other applicants, as intended. With peer institutions, Harvard continues to “try to influence the conversation in Washington” about sponsored-research funding. As of early autumn, possible leading indicators of financial weakness—fundraising, donors’ fulfillment of pledges, executive-education enrollments—remained intact. “You always want to be prepared,” Shore said, “but don’t want to be in a mode of ‘The sky is falling.’”

Over time, he said, financial strength provided by the endowment has enabled Harvard to support and attract faculty members at times when the economy constrains the academy generally. Harvard’s mechanism for funding interdisciplinary science, and housing it in new Allston facilities, is encouraging intellectual progress: “We have a lot of deans now who are eager to recognize and work with the synergies that exist among these schools.” Realizing the deans’ “big, big aspirations” for intellectual advances will require a careful balance of fundraising, debt financing, and effective use of existing resources, Shore said—now overlaid with a pointed recognition: “Given that endowment income is such a big part of our operations, if returns get choppy, it’s something we’re going to have to manage to.”