For all the hand-wringing over their failure to amass savings, Americans may actually be too disciplined. So says Harvard Business School assistant professor Anat Keinan.

A need to feel efficient, and a tendency to feel guilty when we do something “just for fun,” may be universally human. But the Israeli-born Keinan says productivity-obsessed Americans take this to an extreme, viewing pleasurable pastimes as wasteful, irresponsible, and even immoral. Keinan and Columbia Business School professor Ran Kivetz call this hyperopia—the habit of overestimating the benefits one will receive in the future from making responsible decisions now. They write that this phenomenon—the name, drawn from ophthalmology, means “farsightedness”—works to our detriment by driving people “to underconsume precisely those products and experiences that they enjoy the most.”

Keinan began thinking about hyperopia after noting a trend among fellow doctoral students at Columbia: she and her friends complained about not having had enough fun as undergraduates, but they were still staying in on weekends and passing up travel opportunities in favor of work or studies. She wondered why they seemed stuck in these remorse-inducing behavior patterns.

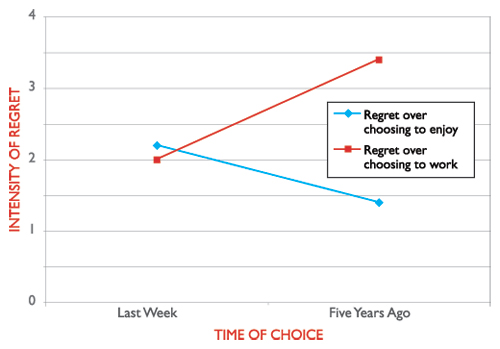

Keinan and Kivetz set out to see if they could observe, in formal studies, people overestimating discipline’s payoff and underestimating future feelings of having missed out. Time after time, when subjects were asked to recall situations in which they had to choose between work and pleasure, their responses emulated those of the Columbia doctoral students. More of the subjects who’d chosen play over work recently expressed regret, but those numbers reversed for choices made in the distant past. For instance, college students said they’d spent too much time relaxing during a recent winter break, but when they considered the previous year’s break, they said they’d spent too much time studying and working.

Keinan and Kivetz, "Repenting Hyperopia: An Analysis of Self Control Regrets," Journal of Consumer Research, September 2006

Regrets About Work Versus Pleasure. When people are asked to recall a situation that occurred either last week or at least five years ago, in which they had to choose between work and pleasure, they rate their levels of regret differently. For decisions made within the last week, subjects are more likely to regret having chosen enjoyment over work. But when considering decisions made more than five years ago, the opposite is true: more subjects regret choosing work.

Whether the choices offered were a week’s vacation versus a week of work with extra pay, a drug-store gift certificate versus a subscription to a popular magazine, or chocolate cake versus fruit salad, the free-spirited choice invariably induced more guilt in the near term—but over time, Keinan reports, regrets about pleasures forgone became more salient than satisfaction at having acted responsibly. These results also held true for study participants recruited in airports, bus and train stations, and public parks.

There are indications that we are aware of this psychological process, at some level: the results were the same even when subjects were prompted to consider hypothetical future regrets—or to make actual choices in real time. When offered five dollars in cash versus a box of chocolate truffles as a study-participation reward, subjects cued to think about the distant future were more likely to choose the instant gratification of sweets.

Based on interviews conducted for some of the studies, Keinan suspects that groups at each extreme are exceptions—overachievers so driven that they lose all capacity to take pleasure in leisure activities, and people leading lives so thoroughly hedonistic that they have no responsible decisions to regret. But “most of us,” she says, “are in the middle. We think it’s important to work and have goals and accomplish them, but also think that other things”—family, friends, physical fitness, hobbies—“are important.”

Keinan teaches marketing, and admits that companies could capitalize on this bias in human decisionmaking (for instance, by placing ads to cue anticipation of future regret over that family vacation never taken). But a broader application is helping people make choices that make them happier. “Why,” she asks, “do we have to wait until we are 60 or 70 to realize what’s really important to us?” The formula she suggests: recognize the tendency to prioritize short-term guilt over late-in-life regrets and make decisions that emphasize the long view. This also helps determine when taking the vacation is not the right decision: “If you think, ‘Ten years from now I’m going to wish I finished this project on time,’ then that’s probably the right thing to do.” She even offers an approach to assuage guilt for die-hard productivity devotees: frame a frivolous choice now as an investment in fond memories and future happiness.