A typical laser is supposed to emit a tight monochromatic beam of coherent light. That’s the common view. But Wallace professor of applied physics Federico Capasso and postdoctoral researcher Nanfang Yu, Ph.D. ’09, have created tiny semiconductor lasers that can emit many beams of laser light in multiple wavelengths from a single source. Their breakthrough work, conducted in partnership with Hamamatsu Photonics and ETH Zurich, may find application in high-throughput analysis of chemicals found in the atmosphere or on the ground, the monitoring of greenhouse gases, or even the detection of hazardous biological or chemical agents on the battlefield.

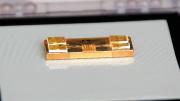

Yu and Capasso have been working on manipulating laser light wavefronts in a variety of ways. Their work takes advantage of a special property of light: it moves along the surface of certain materials, such as gold. Creating an aperture in the laser’s facet (the face of the semiconductor from which the light is emitted) that is smaller than the wavelength of the light being emitted causes the light to diffract in a cone that originates at the aperture (think of a pinhole camera). A fraction of this light actually diffracts 90 degrees along the surface of the gold-coated facet in the form of electromagnetic waves—so-called surface plasmons. If they etch nanoscale grooves into the gold facet at intervals that are precise multiples of the wavelength of the laser light, the light “trips” into the grooves and is then emitted as a new beam, parallel to the original, from the surface of the facet. Such collimation—the creation of a parallel beam of light—is typically achieved with glass lenses. Yu and Capasso’s approach obviates that need.

Further manipulations of beam characteristics such as intensity and direction are possible by altering the length of the grating (i.e., the number of grooves) that scatters the surface plasmons, and by changing the spacing (or “periodicity”) of the grooves, respectively. By patterning two gratings side by side and controlling their respective distances to the laser aperture, one can even create two overlapping beams with 90-degrees phase difference. In this way, the two become a single circularly polarized beam. Such a rotating beam, says Yu, could be used to detect the chemical handedness (chirality) of biological molecules such as sugar, DNA, and proteins.

There are practical advantages to producing multiple beams from a single laser. Rotch professor of atmospheric and environmental science Steve Wofsy, for example, uses lasers developed by Capasso in his research because he considers them “uniquely capable” of making high-resolution sections of the atmosphere that provide new data about the locations and strengths of emissions of greenhouse gases. But to conduct such mass spectrometry in the atmosphere requires both a probe beam and a reference beam. The former interacts with an atmospheric sample and then recombines with the reference beam to reveal the sample’s properties. Today, this requires two separate lasers. Having both beams originate in a single laser will halve the weight of Wofsy’s measuring device.

Capasso’s 1994 development of the quantum cascade laser led to commercial applications a decade later. If past is prologue, the innovative techniques he and Yu have developed for wavefront manipulation will likewise eventually appear in consumer electronics.