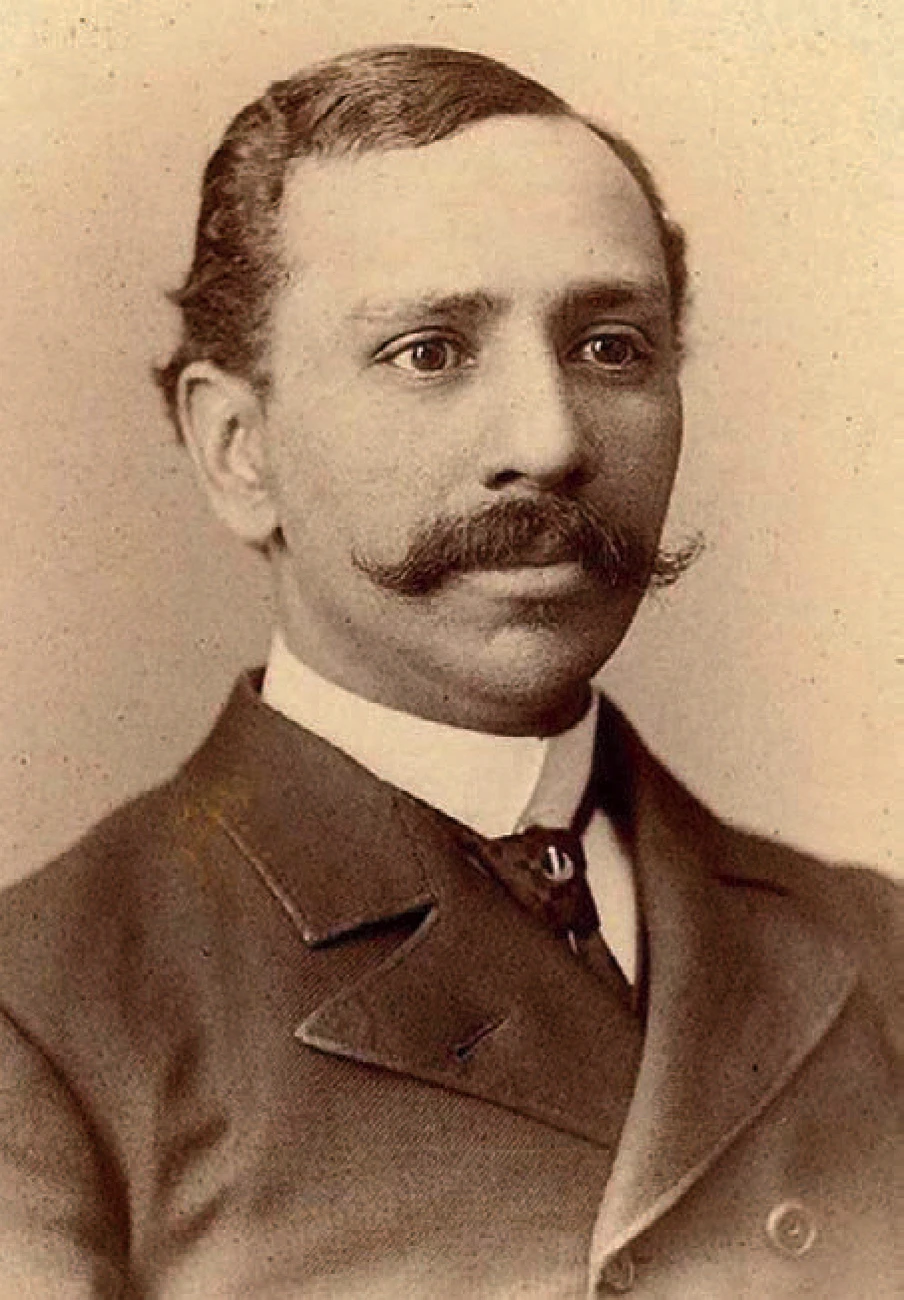

In Black Moses: A Saga of Ambition and the Fight for a Black State (Riverhead, $33), journalist and Northeastern University professor Caleb Gayle, M.B.A.-M.P.P. ’19, tells the story of African American leader Edward McCabe. The businessman and rising political star tried to found a state for Black people in the wake of the American Civil War and Reconstruction. And he nearly succeeded. The passage below, adapted by the author from the book’s penultimate chapter, gives a sense of what McCabe was up against.

Public memory of civil rights lawsuits often centers on the South, overlooking the ways Black ambition collided with legal limits in the American West. But a closer look at one Oklahoma lawsuit—filed by a once-powerful Black political figure—reveals just how early and deliberately the law worked to shut that ambition down.

By the 1910s, Edward McCabe—once the most influential Black political figure in the Oklahoma Territory—had seen his grand vision of a Black-governed Oklahoma unravel. But if political ambition was no longer a viable path, McCabe found a new battleground: the courts. In his final act of public resistance, he filed suit against the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company—a case that would reach the U.S. Supreme Court and spotlight the limits of equality under the law.

The injustice was both symbolic and structural.

The very first law passed by Oklahoma’s newly formed legislature mandated racially segregated train cars. It was more than policy—it was priority. While white passengers were guaranteed quality accommodations, Black passengers who purchased the same tickets were frequently denied comparable service in the “Negro Cars.” McCabe had recruited thousands of Black people to Oklahoma who experienced this disparity firsthand. He brought suit in his own name, arguing that the company’s refusal to provide equivalent first-class cars for Black travelers violated both Oklahoma’s Separate Coach Law and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Despite losing in lower courts, McCabe pushed forward. In 1914, McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Co. reached the U.S. Supreme Court. He no longer held political office; his former newspaper was collecting dust; and his finances were dwindling. What he had was a name on a lawsuit that dared to test whether “separate” would ever be meaningfully equal.

But the Supreme Court didn’t rule in McCabe’s favor because he had not personally been denied service, and the Court declined to weigh in on the law’s application. In doing so, it sidestepped the deeper issue at the heart of McCabe’s claim: that discrimination was not merely a hypothetical—it was a pattern hiding behind technicality.

Still, by bringing the case forward, McCabe exposed something foundational about Oklahoma’s—and the American West’s—new identity. The state’s first legislative act had not been to build a school, fund a bridge, or extend the vote. It had been to codify separation—to declare, from day one, who this state was for.

This lawsuit would be McCabe’s final major public act. He would not found another all-Black town or hold another office. But in placing his name before the highest court in the land, he insisted that Black citizens had not given up on equal treatment—even if the legal system seemed determined to defer that possibility to someone else, some other day.

Sometimes, the last stones a man turns over are the ones that reveal just how much of him still refuses to be buried.