Kristin Kimball ’93 says her undergraduate adventures as an underpaid, sleep-deprived writer for Let’s Go travel guides fostered a desire to see and experience new ways of living. A decade later, when she was freelancing as a writer in Manhattan, her passion for pursuing “the next novel thing” took her in a truly unexpected direction.

While researching a story about the local organic food movement, she met her future husband, Mark, in his rundown farm office-cum-home trailer. He asked her to help hoe the broccoli and slaughter a pig. Soon, she was smitten with the food, the farming, and the farmer. When he asked her to leave the city to start an organic farm together, she took the chance. In The Dirty Life: On Farming, Food, and Love (Scribner), she reflects on the seduction of such a life.

Transitioning was hard. Mark, a Swarthmore graduate, had worked on 40 farms to supplement his custom major in agriculture, but Kimball feared debt and insolvency. Sometimes, only the sheer amount of work required kept them together: “Do it now, or some living thing will wilt or suffer or die. It’s blackmail, really,” she writes. The two overcame differences and tied the knot under one name—he took hers—signifying their commitment to farming as a family: a venture both seemingly traditional and subversive in contemporary America.

Their farm, located in Essex on the shores of Lake Champlain in upstate New York, has been growing. Eight full- and part-time workers help Mark, Kristin, and their three-year-old daughter, Jane; and another Kimball is on the way. Currently, 130 members—most within a 90-minute drive—purchase annual farm shares to receive its organic food at weekly distributions. The local community—a town of 700, very different from Cambridge and Manhattan—embraced the family: Kimball writes, “I think they felt it was their duty to support us, underdog to underdog. Some became members, others helped us in different ways, with tools or advice, by joining us for a few hours at chores.”

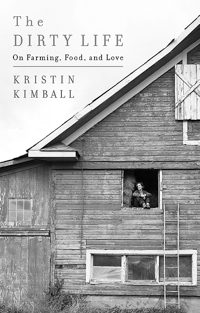

Courtesy of Scribner

Most farms based on this Community Supported Agriculture model produce only vegetables, but Essex Farm also offers meat, poultry, dairy, grains and flour, and maple syrup. Relationships with members are fruitful, Kimball writes, “Distribution days became more like social events than grocery shopping.”

The perception of “the farmer as hayseed” is changing, she notes, but her parents at first were dumbfounded by her decision to trade the options her Ivy League degree offered for grinding work and potential poverty. Thankfully, she says, their initial dismay has evaporated: “They no longer think I’m completely nuts! Now, smart young people choose to do this.” Recent grads from Cornell, Yale, Brown, and Princeton have exchanged sweat for knowledge at Essex Farm.

Though this trend wasn’t as evident when she began farming, Kimball knew she had stumbled onto “an awfully good way to live”: “I get to work with family and there is a direct, concrete connection between the work put in during the day and the outcome.” It’s the toughest work she has ever done—physically, emotionally, and intellectually—and she says Harvard was excellent preparation, “because for a lot of people, it’s their first experience of not being best at something.” In farming, she stresses, so many variables are beyond control—disease, animal behavior, weather—that imperfection is the rule. Farming has also brought ethical issues home, she adds. Agrarian realties impel her to empathize with both organic and conventional farming perspectives on topics like antibiotics use, while hand-to-hand combat with invasive species attracted by rising temperatures bears witness to global warming.

“The farm is a farmer’s golden handcuffs,” she jokes. There’s no going back once you try the food. She describes walking with Mark in the fields after a long day of work and seeing the first cherry tomatoes of the season glowing in the sunset: minute, golden reminders that she has the best job in the world.