Physicists at THE Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have conceived of a device that could produce energy from the infrared radiation naturally emitted from Earth into outer space. Wallace professor of applied physics Federico Capasso, the principal investigator and Hayes senior research fellow in electrical engineering, describes the concept as “the use of physics at the nanoscale for a completely new application.” (For more about Capasso and nanoscale physics, see “Thinking Small,” from the January-February 2005 issue)

“It’s not at all obvious, at first, how you would generate DC power by emitting infrared light in free space toward the cold,” Capasso acknowledged in a press release. “To generate power by emitting, not by absorbing light, that’s weird. It makes sense physically once you think about it, but it’s highly counterintuitive.”

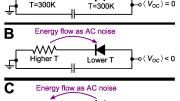

The device would resemble a photovoltaic solar panel, but instead of capturing incoming visible light, it would generate electric power by releasing infrared light. (A full description will be published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.) “Sunlight has energy, so photovoltaics make sense; you’re just collecting the energy. But [the physics of the process are] not really that simple, and capturing energy from emitting infrared light is even less intuitive,” lead author Steven J. Byrnes ’07, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS said in a press release. Byrnes added that it was not obvious even to his team how much power could be generated or even whether it was worthwhile to pursue until they sat down and did the calculations.

The power of the device, Byrnes points out, is modest but real. It “could be coupled with a solar cell, for example, to get extra power at night, without extra installation cost,” he explains, generating a few watts per square meter, day and night.

“People have been working on infrared diodes (a two-lead semiconductor light source that uses less energy than many incandescent light sources) for at least 50 years without much progress, but recent advances such as nanofabrication are…making them better, more scalable, and more reproducible,” says Byrnes. “Now that we understand the constraints and specifications, we are in a good position to work on engineering a solution.”