November 19, 2011. The Yale Bowl. There are seven minutes remaining in the second quarter and the heavily favored Harvard football team is being given all it can handle by scrappy archrival Yale. Nursing a 14-7 lead, the Crimson has driven to the Eli 5, where it faces a fourth down and goal. Given Harvard’s solid field-goal kicker, David Mothander ’14, the orthodox play is to take the points. Let Mothander boot the chip shot and widen the lead to 10 points, making it, in football parlance, “a two-score game.”

Kneeling at the 12, presumptive holder Colton Chapple ’13 takes the snap from center. But wait! Instead of plunking the ball on the ground in preparation for the placekick, Chapple pitches it to Mothander, who in his previous football life was a quarterback at St. Margaret’s Episcopal School in San Juan Capistrano, California. Mothander sets sail around the Yale left end—vacated by unwary Elis defenders—and waltzes into the end zone. On the next snap, he does kick the ball through the uprights. The extra point gives Harvard a 21-7 lead. There are almost 37 minutes to play, but for all intents the game—The 128th Game—is over. The Crimson goes on to win 45-7, matching its largest victory margin in the series and completing an undefeated Ivy League season.

The architect of the strategy—the man who gave the green light to the fake—was Harvard head coach Tim Murphy. The maneuver revealed the essence of his philosophy as well his uncanny talent for taking the temperature of a game. The prospect of failure (and the second-guessing of Sunday-morning quarterbacks) neither daunted nor deterred him. To Murphy, it was an irresistible gamble. “If you pull it off, they’re on the ropes. You’ve buried ’em,” he explains in his forthright, matter-of-fact fashion. (In appearance and demeanor, he bears some resemblance to the actor Christopher Meloni, best known for playing a blunt-spoken detective on TV’s Law and Order: SVU.) “You go with your gut, and if you have that feel that this is the opportunity to put a team away, there’s a risk/reward that’s worth it.” Such audacity is in his DNA. “We want to take x amount of shots per game,” he says. “Whether that’s an onside kick, a fake field goal, a fake punt, a reverse pass, fill in the blank…you have to have one of those because sometimes you need it to change the tempo of the game, sometimes you need to get back in the game, sometimes you need it to put a team away.”

Now in his twenty-second season as Harvard’s coach—only its third in 59 years, following John Yovicsin and Joe Restic—Timothy Lester Murphy, who turned 59 on October 9, is a master of the art of putting teams away. Beginning in 1994, when he arrived from Cincinnati to replace Restic (23 seasons, 117 wins, five Ivy titles won or shared), through last year, Murphy has amassed an overall record of 147-62. In Ivy play he is 104-43, and he has won or shared eight league titles, including last year when his team was 10-0; a pulsating 31-24 win in The Game capped his third perfect season, to match those in 2001 and 2004. His teams have beaten Yale 16 times in 21 tries. In the Murphy era, the Crimson has outscored the Elis 533-363. Last November’s win—which characteristically featured a trick-play touchdown pass off a reverse from one wide receiver, Seitu Smith ’15, to another, Andrew Fischer ’16—was particularly heartening: It came nine months after Murphy underwent triple coronary-bypass surgery.

Most remarkable is Murphy’s record beginning in 2001: 114-25, the best mark in NCAA Division I’s Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) in that span. It includes 13 wins over Yale in 14 years, and victories in the last eight Games in a row. (Aggregate score in those 14 years: Harvard 403, Yale 215.) During that period, in no season has Harvard won fewer than seven games, a consistency that boggles his counterparts. “It’s almost unheard of in this league,” marvels Jack Siedlecki, Yale’s coach from 1997 through 2008 and Murphy’s roommate when they were youthful assistants at Lafayette. Murphy’s teams have not lost back-to-back games since 2006, when they dropped their final two contests, to Penn and Yale. Harvard has not been shut out since 1998—a span of 168 games and an Ivy record. (For a report on this season’s early games, see “Rolling Along.”)

By longevity as well as accomplishment, Murphy has become Harvard’s greatest football coach, surpassing even pigskin genius Percy Duncan Haughton, A.B. 1899, a seminal figure who from 1908 through 1916 guided the Crimson to a 71-7-5 mark and three national championships. (A frieze dedicated to P.D. is affixed to the open end of the Stadium on the home side.) The Haughton era always has been referred to as “the golden age of Harvard football,” but now it must share space with the Murphy epoch.

During his tenure Murphy also has etched himself on Ivy League football’s coaching Mount Rushmore, along with Bob Blackman (seven titles at Dartmouth from 1955 through 1970), Carmen Cozza (11 at Yale from 1965 through 1996) and Al Bagnoli (10 at Penn from 1992 through 2014 and who is now coaching at Columbia). He has won a passel of awards, including the inaugural Ivy League Coach of the Year honor last year. In 2012 he served as president of the American Football Coaches Association. There is even a budding Murphy coaching tree. But because he prowls the sidelines on most autumn Saturdays before only a few thousand passionate souls, Murphy is not often mentioned in the discussion when sports-talk pundits rank the nation’s top coaches, with names coming from the usual Football Bowl Subdivision power seats: Tuscaloosa, Columbus, Ann Arbor.

Two decades ago Murphy was on track to enthrone himself in one of those seats. Instead, he settled in Cambridge to become the Thomas Stephenson Family Head Coach of Harvard Football. “I made a gut decision that less is more,” he says. “When you put it all together, I could not have conceived how well it would turn out.”

The Apprentice

In the early 1970s, in Kingston, Massachusetts (about five miles north of Plymouth), Silver Lake Regional High football coach John Montosi had on his squads a star quarterback named Eugene (Buddy) Teevens and a scrappy end/linebacker named Timothy Murphy. The two boys and their classmates stare out from the pages of the school’s yearbook, The Torch, looking for all the world like refugees from Dazed and Confused, the iconic Richard Linklater film set in that time period. Growing up, Buddy and Murph were as close as brothers, and remain so, except for the one day each year (this season, Friday night, October 30 at the Stadium) when Harvard plays Dartmouth.

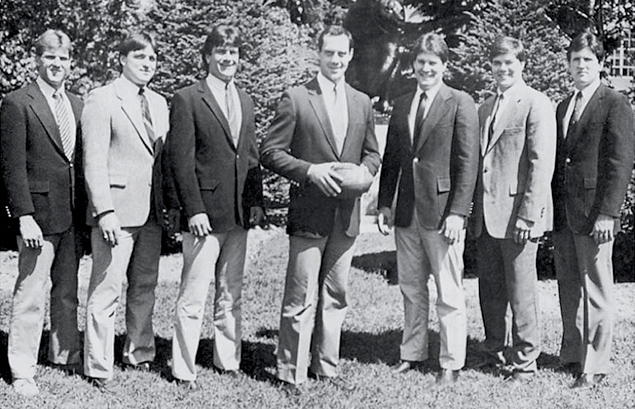

A coaching phenom at Maine

Photograph courtesy of University of Maine Athletic Communications

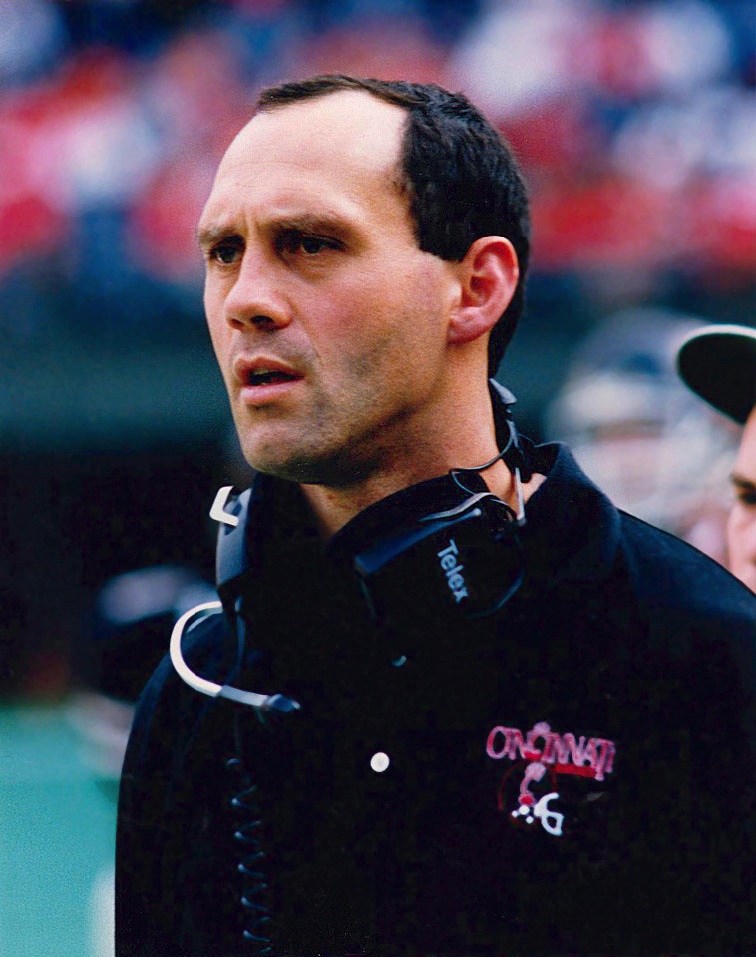

When he moved to Cincinnati, Murphy became the youngest head coach in Division I.

Photograph courtesy of University of Cincinnati Athletic Communications

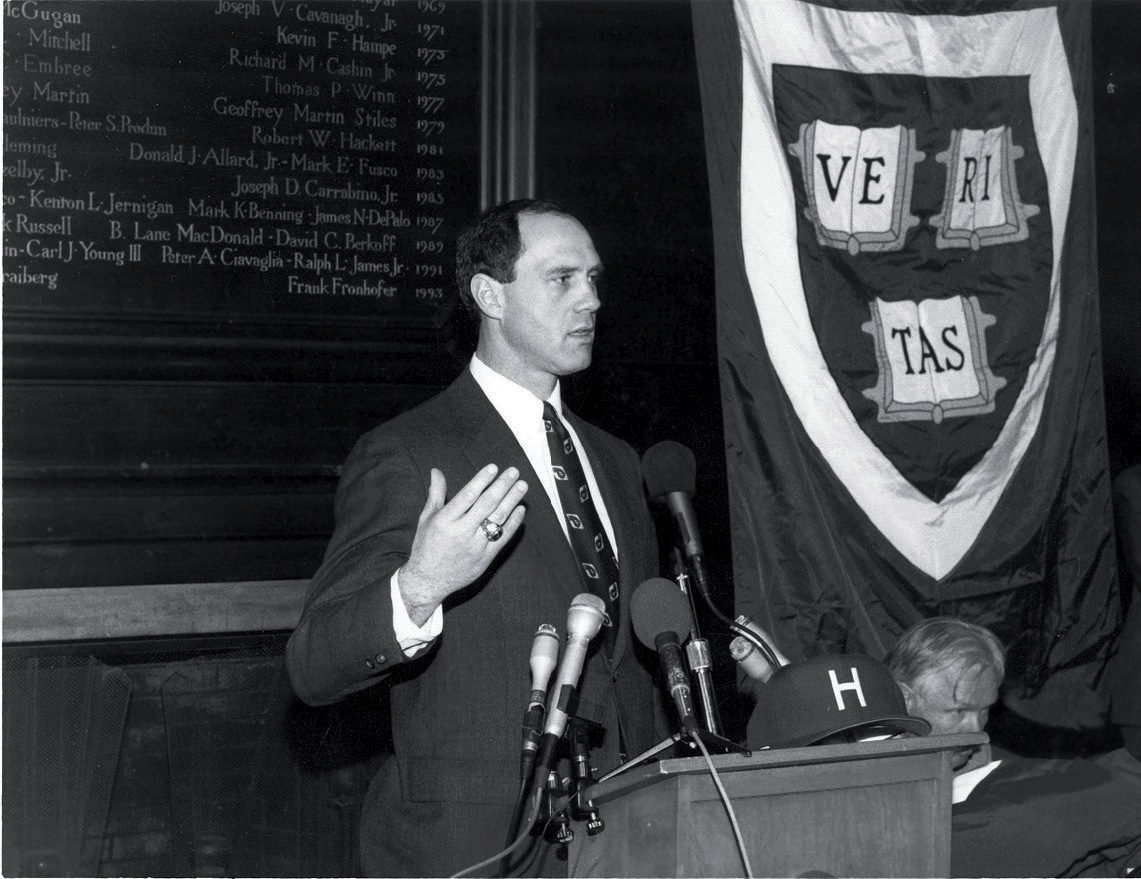

Murphy shocked the profession in 1994 by moving to Harvard.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

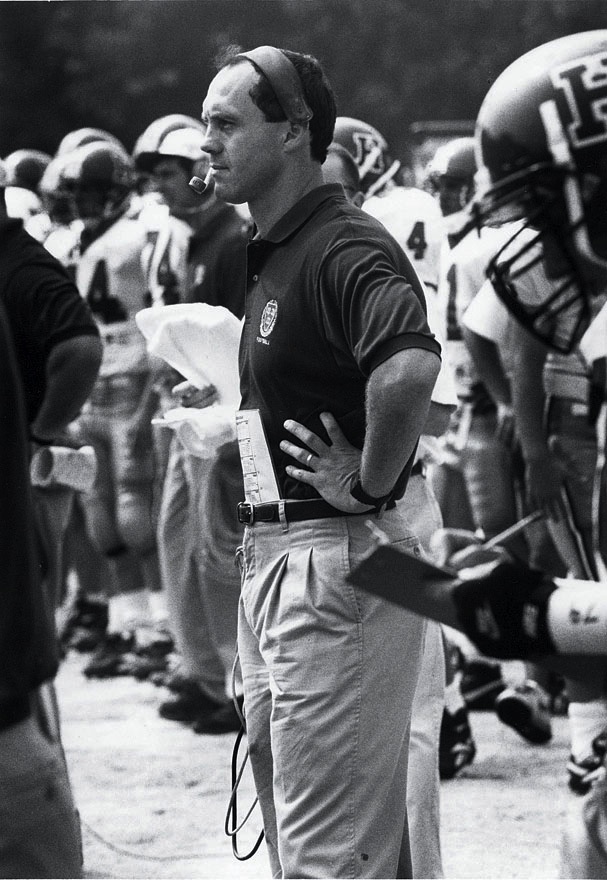

On duty early in his Harvard tenure

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

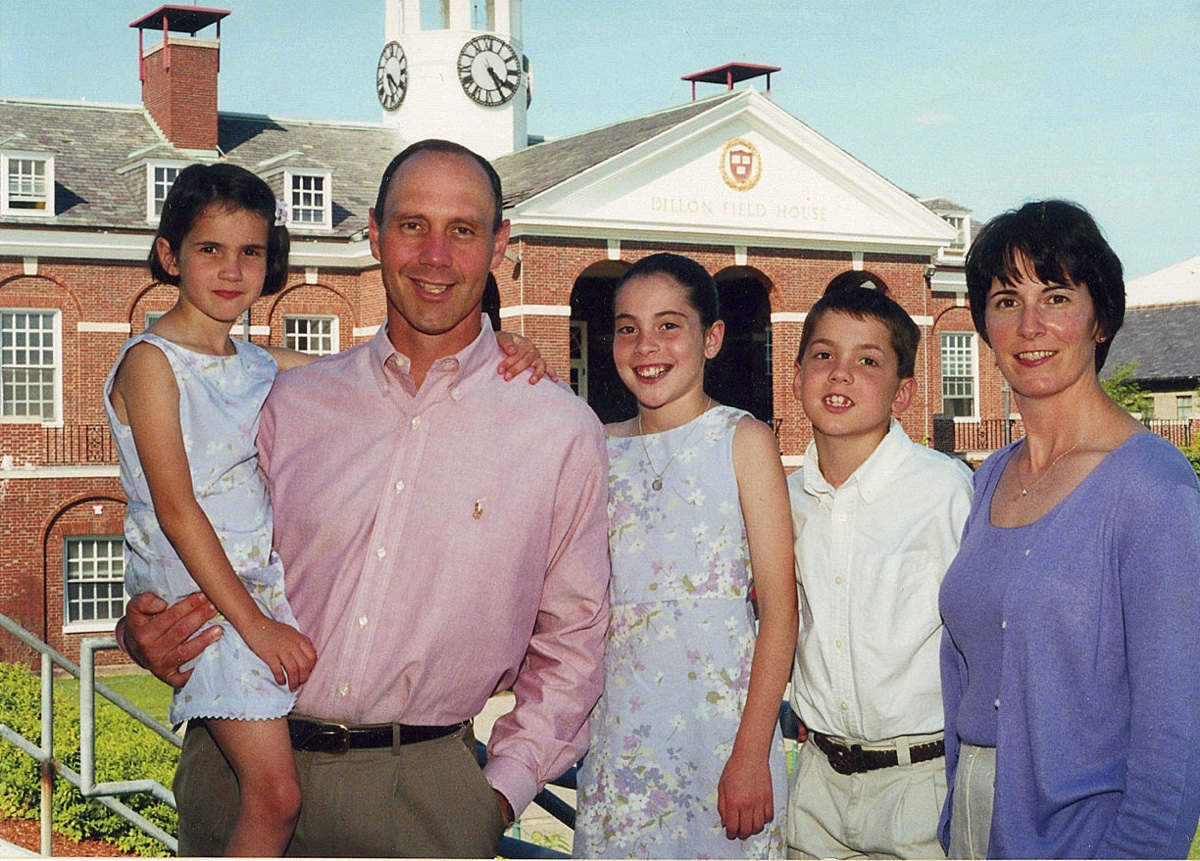

During his first seven up-and-down seasons, the constant was his family (from left): Grace, Molly, Conor, and Martha.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

“If you could have got odds in seventh grade that Buddy Teevens and I would end up Ivy League football coaches, you could have got a million to one,” says Murphy. Buddy Teevens went on to become All-Ivy at Dartmouth and now is in his second stint as head coach of his alma mater.

“He’s never changed,” says Teevens of Murphy. “He’s the guy that I grew up with….Do [things] the right way, do [them] consistently….The essence of who he is has not changed since the first day I met him.”

John Montosi does not admit to envisioning two future coaches, but both boys made an impression. “Timmy was probably the most serious one on the team,” he says. “Probably because nothing was given to him—he had to earn it. He was a late maturer as far as height and weight. [Murphy eventually sprouted to 6-foot-3.] But he became a starting tackle and defensive end and was a very good player. We had one toughness drill that we used to do, and when Timmy was in the middle no one wanted any part of him.”

Montosi made an impression on Murphy as well. “I knew what I wanted to do I when I was a junior in high school,” he says. “Coaches had a huge impact on my life, from a very early age. I’m not positive I can tell you the name of my ninth-grade French teacher, but from my Little League coaches Freddy Smith and Louis Nogueira, to my high-school basketball coaches Dick Arietta and John Cuccinato, to my high-school football coaches John Montosi and Bob Murphy, to my college coach, Howie Vandersea, they had an impact on my life.” They became his role models for male authority. “Those guys, they really cared,” Murphy says. “And you can’t fake caring.”

Though he made all-league, Murphy attracted scant notice from colleges. “I was so sophisticated I went to the school that sent me a form letter,” he says with a chuckle. Arriving at Springfield (Massachusetts) College to play for Vandersea, “I was 175 pounds. Sixteen months later, I was 220 pounds. I talked different, walked different, I played different. The one thing I can take pride in: I was tough, I was resilient, and I was driven. Those are things you can decide to be, or it’s in your wiring, or a combination. That’s who I was.” As a senior, Murphy was named a small college All New England linebacker. “My idol back in those days was Dick Butkus. He was tough, physical, someone you can rely on. I wasn’t a great player, but I loved the game and I played it hard.”

Murphy also was learning from Vandersea, who had his physical-education majors create and present a football playbook. Recalls Vandersea, “Tim had an excellent playbook that was attentive to detail, as was his oral presentation.”

Upon graduation in 1978, Murphy began his coaching apprenticeship as a graduate assistant on John Anderson’s staff at Brown. “I got $800 for the year,” he says. At the same time, “I actually worked in a factory, in an extrusion mill, Union Camp Corporation in Providence, Rhode Island, on the graveyard shift.” Murphy was quickly captivated by the Ivy ambiance. “I met a guy named Mike Kachmer, a Brown engineering student and football player who had been an All-Ivy safety and now also was a graduate assistant,” Murphy says. “He was from Poland, Ohio. We immediately hit it off—two peas in a pod. One day I said, ‘How did you end up in a place like Brown?’” Kachmer replied, “‘My parents always made sure I did my homework, I was a pretty good athlete, highly motivated. All of a sudden I started getting letters from Ivy League schools.’”

“That was an epiphany for me,” Murphy says. “I realized, It’s not enough to have a goal in life—you have to have a plan. As crazy as it may sound, I went back to my office—really a broom closet with a desk in it—and I set a goal that I would be a head coach by the time I was 30, and if not, I was going to go back and get my M.B.A., which when you look back seems really ridiculous.”

After spending another year at Brown as assistant offensive-line coach and a year as defensive-line coach at Lafayette, Murphy prepped for the M.B.A. route in earnest during three years on Rick Taylor’s staff at Boston University. “I took courses I’d need for the GMAT and M.B.A.,” he says. “I remember being in a summer calculus class with freshman engineering majors who were much smarter than I was. I had to figure out a way to get an A, and I did. I had to work way harder than they did.” In 1985, Teevens became head coach at Maine, and he brought along Murphy as offensive coordinator.

After his second season in Orono, Murphy was ready to pack it in: He had applied to and been accepted by Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management and the Darden School of Business at Virginia. He prepared to move to Evanston. “My thirtieth birthday had come and gone,” he says. “Of the five schools I had applied to, the only two that accepted me were the two that required an interview. Which taught me a very valuable lesson: You don’t really know until you meet somebody. So much of it is your gut. That really has become the heart and soul of my own recruitment process—getting a gut feeling about people and making bets on that.”

Before Murphy could become a business student, Teevens resigned to become head coach at his alma mater. Murphy was offered the Black Bears job. “I’d worked so hard to get into a good school and I was so conflicted,” he says. “I asked Kellogg to defer me for a year and I’ll get this head coaching thing out of my system. Twenty-eight years later, I still haven’t.”

The Jagged Path to the Top

When Murphy took over at Maine, he was the youngest head coach in college football. Two years and one Yankee Conference title later, when he moved to probation-wracked Cincinnati, he was the youngest head coach in Division I. (Before relocating, he married Swampscott, Massachusetts, native Martha Kennedy, a health-insurance executive. As a busy two-career couple, they have yet to go on their honeymoon. All three of their children have gone to Harvard: Molly ’14, Conor ’16, and Grace ’18.) He stayed five years. His third Bearcats team lost to Penn State 81-0. The next year Cincinnati gave the Nittany Lions a scare before succumbing 24-22. In Murphy’s final year the team was 8-3—the school’s first winning season in 11 years.

As befits a major-college coach, Murphy was making major money (his compensation included a country-club membership), and he stood to make more—at Cincinnati or at one of the traditional powers. But he had become keenly aware of the job’s pitfalls. Before the Bearcats’ turnaround, “There was an ah-ha moment from my wife,” he says. “We were at a New Year’s Eve party with one of our neighbors. He probably had a little too much to drink, and his back was to us. He said, ‘Yeah, if Murph doesn’t win next year, he should be fired.’ She has never forgiven him. I tried to tell her, that’s the way it is. That’s the job.”

When Restic retired in 1993, Murphy decided to apply for the Harvard post. William J. Cleary ’56, the athletic director at the time, looked beyond Murphy’s overall 17-37-1 record at Cincinnati. “You could see he was a well-organized individual,” says Cleary, who also was wowed by Murphy’s intense preparations for business school. “I said to myself, ‘Any guy who did what he did to try to get ahead, he’s a man who’ll do well at Harvard, because he’s got his priorities set. Obviously, academics means something to him. That’s the type of guy you want here.’” (Adds Cleary, “I have to say that was one of my best hires.”)

Murphy’s move to Cambridge—dropping down, in effect—ran against all the tenets of the coaching food chain. “My assistant coaches were just stunned,” he says. “They said, ‘Coach, you are committing professional suicide.’ And there was a 40 percent pay cut. Even my wife was not without concerns. But there were a couple of things. One, my mom was terminally ill at the time,” and being back in Massachusetts would put Murphy closer to her. “Two, I had just thoroughly enjoyed the experience at Brown—how driven these kids were.”

The Crimson was coming off six consecutive losing seasons, so Murphy set out to instill that same drive. At his introductory press conference, he vowed that Harvard would win the Ivy title within four years—by the time his first set of recruits graduated. Murphy scrapped Restic’s vaunted multiflex offense, which had bamboozled foes but also occasionally the Harvard players, in favor of a no-huddle, hurry-up attack that could wear out a defense. He also introduced a new level of commitment. “It was revolutionary in the attention to detail, conditioning, the hard work, the effort,” says Dan Vereb ’96, an offensive lineman recruited by Restic who played his final two seasons for Murphy. “A couple of the big things were hiring a strength and conditioning coach, and having a specified four-day-a-week workout program that was monitored, in season and out of season. In the off-season, there were running groups at six in the morning. These were new things that didn’t exist under Restic. During the Restic period, on Thursday night if you had a lab, you skipped practice and went to the lab. Under the dedicated concept, you made sure you scheduled your lab on Monday”—when there was no practice. Otherwise, you might not play on Saturday. “This was never done in an intimidating way,” says Vereb. “It was: ‘Hey, you want to win, you got to put the time in.’ ”

Harvard’s players also began to get accustomed to something called “Murphy Time.” As Vereb describes it: “The meeting was announced to start at 9:00, but he started at 8:55. So you learned to arrive at 8:50.” Successive generations of Crimson players have continued to operate in that time zone. Kyle Juszczyk ’13, an All-Ivy tight end, now plays for the National Football League’s Baltimore Ravens. “I still run on Murphy time,” Juszczyk says with a laugh. “I set all my clocks five or 10 minutes ahead.” (And it’s not just the players. When asked for her father’s main precepts, Grace Murphy responds: “Failing to plan is planning to fail. Always be early. Never quit.”)

Finally, to capture some of that school spirit, Murphy began having his players sing “Ten Thousand Men of Harvard” after games and practices. “We had [a fight song] at Maine,” Murphy says. “Cincinnati didn’t have one—so we made one up. At Harvard, when we started this great and sort of iconic tradition, kids [were] like, ‘Coach, this is so corny.’ But I guarantee that the first time they sang it, they got it! The connection was there, and the rest was history.” In the YouTube era, the Crimson’s locker-room renditions after victories have gone viral.

The first three seasons produced a mere 10 of those opportunities for postgame songfests, against 20 defeats, some of them heartrending, including a 6-3 loss to Dartmouth in ’96: the potential tying field goal, attempted on the final play of regulation, clanked off the right upright. Still, some saw the seeds of victory. John Veneziano, who was then the school’s sports information directorand is the author of the football chapter in the recently published Third H Book of Harvard Athletics, says that defeat against the Big Green “was absolutely the moment when I realized the transformation that was taking place with the program. Funny that it came in a loss when the team didn’t even score a touchdown, but the fight that was in the Harvard kids that day left no doubt where the program was heading. Even stranger, that was our eleventh straight home loss—losing to Brown the following week made it 12. So where it may have been easy for some to see despair and frustration, if you stepped back, you saw that something special was on the horizon.”

Everything came together in 1997, Murphy’s fourth year—just the way he had drawn it up. Behind such stalwarts as (among others) quarterback Rich Linden ’00, running back Chris Menick ’00, offensive lineman Matt Birk ’98, linebacker Isaiah Kacyvenski ’00, and defensive end Tim Fleiszer ’98—all players brought in under Murphy—Harvard was 7-0 in the Ivy League (its first title since 1987) and 9-1 overall, with only a 24-20 loss to Bucknell marring perfection. “It seems like a linear thing, but it’s not,” says Murphy of the jagged path to the top. “But we made a commitment to that first class, that if you come here we will win an Ivy championship. So that year was special.”

But the next three seasons saw a regression to mediocrity, marked by some of the most excruciating losses in Harvard football history, including two nailbiters to Yale and a humiliating collapse in 2000 at the Stadium against Cornell, which rallied from a 28-point deficit to win 29-28. “When you get used to winning, the lows are much lower than the highs are high. I remember the losses a lot better than I remember the wins,” says Murphy, who ranks this debacle with 2012’s 39-34 defeat at Princeton as his two most brutal setbacks. (That day, the other Murphy’s Law truly prevailed as the Tigers rallied for 29 fourth-quarter points.) “I take full responsibility,” say Murphy. “I remember vividly coming home [from the Cornell game] and my wife said, ‘Conor really wants to play football with you.’ And I said, “I just can’t…” But when you’re home, you’re home…so I grudgingly went out. An hour later? You couldn’t believe how therapeutic it was. A reminder that this football stuff is not life and death. We’re not curing cancer.”

After seven seasons in Cambridge, Murphy’s record was 33-37. Against Yale he was 3-4. If this had been another school in today’s what-have-you-done-for-me-lately world, it’s possible Murphy would have been jettisoned, to be ranked just above two postwar Crimson coaches, Arthur Valpey (1948-1949, 5-11) and Lloyd Jordan (1950-1956, 24-33-3). And everyone would have missed out on the next 14 years.

The Educator

The twenty-first century has seen what seems an assembly line of Harvard football greats. The honor roll is worth reciting, if only to show the waves opponents have had to confront. At quarterback, Neil Rose ’03 has yielded to Ryan Fitzpatrick ’05 to Chris Pizzotti ’08 to Collier Winters ’12 to Colton Chapple to Connor Hempel ’15. They have handed the ball off to running backs Clifton Dawson ’07 and Gino Gordon ’11 and Treavor Scales ’13 and Paul Stanton Jr. ’16, and thrown it to Carl Morris ’03 (a two-time Ivy Player of the Year), Brian Edwards ’05, Corey Mazza ’07, Matt Luft ’10, Kyle Juszczyk, Cam Brate ’14, and Andrew Fischer while being protected by Justin Stark ’02, Brian Lapham ’05 James Williams ’10, Kevin Murphy ’12, Nick Easton ’15, and Cole Toner ’16. The defense has featured linemen Mike Berg ’07, Desmond Bryant ’09, Matt Curtis ’09, Josue Ortiz ’12, Nnamdi Obukwelu ’13, and Zack Hodges ’15, linebackers Dante Balestracci ’04, Bobby Everett ’05, Glenn Dorris ’09, Alex Gedeon ’12, Bobby Schneider ’13, and this year’s captain, Matt Koran ’16; and defensive backs Andy Fried ’02, Sean Tracy ’05, Steve Williams ’08, Doug Hewlett ’08, Andrew Berry ’09, Derrick Barker ’10, Collin Zych ’11, and Norman Hayes ’15.

At times the riches have been embarrassing and perhaps overwhelming to foes struggling to find one decent player at each position. In 2001 against Princeton, the injured Rose—who would be named All-Ivy—was replaced by freshman Fitzpatrick, who later would be a worthy NFL quarterback. (He’s now with the New York Jets.) Fitzpatrick guided the Crimson to a 28-26 win. The next week, after falling behind 21-0 at the half, the Crimson rallied behind Fitzpatrick for its largest comeback ever, a 31-21 win that was a highlight of Murphy’s first perfect season. (In 2004, Fitzpatrick and Harvard matched that bounceback, beating Brown 35-34 after trailing 31-10 at the half.) In 2012, at the varying position of tight end/H-back (the latter lines up similarly to a tight end but a step in back of the line), Murphy could deploy two future NFLers, Juszczyk and Brate.

Just as telling, though, are the times when the talent is not A-list. “They’ve had superstars and they’ve had pluggers,” notes John Veneziano, who cites the 2001 season, when two undersized backs—5-foot-8 Nick Palazzo ’03 (556 yards) and 5-foot-10 Josh Staph ’01 (492)—were the rushing leaders.

Opposing coaches are in awe not only of Murphy’s ability to evaluate and attract such athletes, but also of the way he and his staff use them. Al Bagnoli is the one coach who has had Murphy’s number; his Penn teams won 11 of 21 games against the Crimson. “I know Harvard is Harvard, but you still have to go out there and find the kids and develop the kids,” Bagnoli says. “And they do as good a job as anybody in terms of identifying kids and then working with them. And that’s really a credit to [Murphy].

“Offensively, they utilize their personnel in so many different capacities,” he continues. “When they had Kyle Juszczyk, they had him all over the place. He could have been a split receiver, a fullback, an H-Back. And they did that with both tight ends. They’re not afraid to deploy big kids on the perimeter. Usually when that happens, you see wide receivers run into the game and you can match up. The versatility of their kids is an asset. They do a great job of making you think about where everybody is.”

Murphy’s End Game

As Harvard has thrived on offense under Tim Murphy, the roles of tight end and H-back have come to the fore. The tight end is the player aligned at the end of the line, originally next to one of the tackles (hence the name). The H-back lines up similarly, but a step behind the line. Murphy uses the same players at either spot. Each demands a blend of toughness (crucial for blocking), pass-catching ability, and speed. This year three tight ends/H-backs have contributed to Harvard’s early-season success: Ben Braunecker ’16, Anthony Firkser ’17 (second-team All-Ivy in ’14) and Jack Stansell ’18.

What accounts for the excellence of Crimson tight ends/H-backs? Superior athletic ability, Murphy’s position coaching—and ingenious schemes. They can line up in no fewer than 15 formations, from which any play can be run. Some, such as Pro or Trips, with the tight end and/or H-back in close to the running back, seem to indicate a rushing play. Others, such as Doubles, which has both players flanked, seem to signal a pass. Defensive coaches can try to ferret out tendencies, and still guess wrong.

One formation Harvard uses devastatingly is Bunch Trips: aligning the tight end and H-back on the flank with the wide receiver. If the quarterback passes to that side, he has three potential receivers and two blockers to lead the pass-catcher downfield.

Note: The visual feature below is optimized for modern browsers. If it does not work in your browser, try the latest version of Google Chrome, Apple Safari, Mozilla Firefox or Microsoft Internet Explorer.

Twins | Hip Twins | Doubles | Bunch Trips | Ace

As you watch the particular formation develop, imagine you’re the other team’s linebacker. What defense would you call?

The wealth of talent has given Murphy the luxury of mixing things up. “Balance is really important, because the minute you become statistically predictable, you are in big trouble,” he says. In this respect, last year’s undefeated team was an offensive paragon: It averaged 230.5 yards a game rushing and 230.9 passing. (You’d be hard-pressed to find a more amazing sports statistic, unless it is career hits of St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Famer Stan Musial: 1,815 at home and 1,815 on the road.)

On defense, says Bagnoli of the Crimson, “They don’t give up vertical plays [for long gains downfield]. When you score against them, you really earn it. They’re really sound schematically. They do enough to keep you off balance, but not so much as to confuse themselves.”

Murphy is a savvy and flexible motivator, but no pushover. (“He is a combination of a lawyer, a priest and a drill sergeant,” The Boston Globe’s Bob Monahan once wrote.) “I broke my hand my junior year and missed the next few games,” says Fitzpatrick. “I told him I was completely healthy and ready to go. I played in the Dartmouth game—badly. It was probably too early. We didn’t talk for a week and a half or two weeks. We’d pass in the hallways and he’d give me the cold shoulder. It was almost like he was a father but he knew how to get to me and show me how disappointed he was” for not being completely honest.

There are other ingredients to Murphy’s success. “One thing he teaches is how important it is to overcome adversity,” says Paul Stanton Jr., whose brilliant running keyed a second-half comeback against Penn last year. “He’s always calm, cool, and collected. He tells us that we know we’re the better team and train harder than anyone else.” Beneath that even exterior, though, his players can sense the churn. Dante Balestracci likens it to “watching a duck swim. It looks smooth and effortless, but if you had a camera underneath, those legs are absolutely flying.” Nevertheless, says Balestracci, Murphy’s “ability to steer the ship and keep that calm demeanor always resonated with me.”

Another element in Murphy’s success is his audacity. As he proved with that fake field goal against Yale in 2011, Murphy will go for it—even on fourth down in his own territory. “As a player, I really love that,” says Stanton. “It shows everybody on the field that he believes in us.”

Finally, there is his ingenuity, particularly at crucial moments. “There’s always one play you haven’t seen till the Yale game,” says Veneziano. Former Eli coach Siedlecki notes how his old roomie keeps opponents awake at night: “By the time we played Harvard, we’d seen eight to 10 junk plays—the reverse passes, the double reverses—on film, and at least two or three punt fakes. One year they had a run play off of which came five different reverse passes or flea-flickers. I said to my staff, ‘I don’t know what [the gimmick] will be [this year] but it will come off of that play.’ You need to spend time [preparing for] that stuff. And that takes away from your preparation for some of the other things.”

The Organization Man

“There’s only one way you can do this job: 100 miles an hour and your hair on fire,” says Tim Murphy. “That’s just the way it is.”

He is sitting in his orderly office on the first floor of the Dillon Field House. Opening kickoff is still almost 12 weeks away, but activity is ceaseless, particularly with prospective recruits on the phone. “People have an impression of the Ivy League that it has a Division III mentality,” he says. “You’re a good guy, you can coach forever.” During his tenure, Murphy has seen 22 coaches at the other seven schools come and go. “I say, Listen: Our alums are like all alums. These are really smart people, really competitive people. Trust me on this: There is not as much patience as you might think.”

For Murphy, to every thing there is a season. “One thing I love about my job is that every three months the landscape kind of changes,” he says. “You go through the competitive season in which you work 100 straight days, 100 straight 12- to 15-hours shifts without a day off—and if you went much longer it would kill you. It’s like being on a submarine. I don’t watch any television during the season. Zero.

“Then you’re into your formal recruiting period, where you’re on an airplane five days a week and flying home on weekends. Then your developmental phase: offseason strength and conditioning and spring football. Then the organizational phase where you [plan] the upcoming 12 months, and speaking and fundraising for our program.”

He points to a loose-leaf binder. “Every summer I’ll plan the next 12 months, and I’ll give [this] to my staff and players. Maybe it’s a little bit compulsive,” he says with a laugh. “But it’s so everybody is on the same page.” Sure enough: If you want to know where you’re supposed to be on February 11 at 6:30 a.m. (the answer: strength and conditioning), you need only consult the guide. He also provides his players with a summer reading list. This year’s featured 11 books, including Gates of Fire by Steven Pressfield (“historically accurate and epic novel of the Battle of Thermopylae. Makes ‘300’ seem like a cartoon”) and The Big Short by Michael Lewis (“Author is pretty impressive for a Princeton grad. Story about the market crash in the 21st century. Fascinating take on how so few saw it coming and how so few profited.”).

Workouts and game weeks are similarly mapped. “Practices are completely scripted, generally in 24 five-minute blocks,” he says. “Within each block, we script what the tempo is: is it high and hard? Polish? Scrimmage? The Ivy League adopted a rule about five years ago to never hit two days in a row in practice. I’ve been doing this for 25 years. I believe it’s like boxing. You need x amount of live punches, but you want to minimize it as much as you can. One of the reasons I think we have been so successful in a very rugged schedule in November over the years is that we are as fresh as any team that we play….We’ve probably done less hitting here than any team in the nation. But when we do it, it’s highly intense.”

Murphy is the position coach for the tight ends/H-backs. “He was a phenomenal teacher,” says Juszczyk. “I really feel that that’s where I honed most of my skills. He really challenged me. When I showed up [in Cambridge], I felt pretty good about myself as a player, but he used the ‘break ’em down to build ’em up’ technique on me. There were times during my freshman year when I went back to my dorm room and I wondered if I should even be there. But after a tough year of coaching he started to see what he wanted from me and we had a really positive relationship from then on.”

Once play begins, coaches and players are on a treadmill. “Sunday is a long day,” says Murphy. “At one o’clock p.m., the kids report to sports medicine. At two, there’s strength and conditioning. From three to five you go over the video from the previous game. At five o’clock you have a meeting on the field to showcase your next opponent. Monday is a day off mandated by the NCAA.” But not for the staff. “We get the video Monday morning [of the next opponent]. We also get statistical computerized analyses of all tendencies—field position, down and distance, personnel….We’ll watch all the situations and formulate a game plan, bit by bit.

“Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday are the same: a three o’clock meeting, four o’clock practice, off the field at six. In season we don’t do any scrimmaging. We call it high and hard tempo: nobody leaves his feet, kind of an NFL mentality. Thursday—and I’ve been doing this for 30 years—we take the pads off.” No protective gear means no blocking or tackling. “On Friday we have what we call a ‘mental practice.’ We go through every possible scenario of the coming game. Every position on our team has a test. To some extent, we tell our players that this is a take-home exam.”

The Recruiter

The phone rings. It is a prospective recruit. Murphy provides guidance on courses that might buttress his transcript for the admissions committee. (He has gone through this process, after all, with his own children.) The pool of good football players who also have the academic record to get into an Ivy school is small, and every coach in the league knows who they are.Murphy and his coaches (helped by the generosity of the Friends of Harvard Football) range far and wide to find them. Last year, Texas and Georgia each supplied the roster with 13 players; the winning touchdown pass against Yale went from a Kentuckian (Hempel) to a Californian (Fischer).

Murphy says he is not necessarily seeking a specific kind of player, but does concede, “We look for three-sport athletes. We think those kids have the most potential.” Offensive coordinator Joel Lamb ’93 says that the task during recruiting is to look beyond what’s on film and fasten on players “who will be a good fit for Harvard football, as well as having great off-the-field qualities to make them successful at Harvard.” Ryan Fitzpatrick zeroes in on Murphy’s favorites: “He’s going after blue-collar, humble kids who are willing to put in the work. Either they have overcome [adversity] or come from great families.” When Fitzpatrick was being recruited out of Highland High in Gilbert, Arizona, “My parents were nothing but impressed with the way he presented himself—especially his honesty. He’s brutally honest about his expectations of each player. He won’t sugar-coat it. You have to work for your grades, and for your playing time.”

While keeping tabs on recruits, Murphy is also touching base with former players and staffers. By his count, nine former assistants have become head coaches, most notably the Baltimore Ravens’ John Harbaugh (Murphy’s special teams coordinator at Cincinnati), the Miami Dolphins’ Joe Philbin (offensive-line coach and coordinator at Harvard from 1997 to ’99) and Yale’s Tony Reno (the Crimson’s special-teams coordinator from 2009 to ’12). Kyle Juszczyk reports that on the Ravens, he and Harbaugh bond with two other Murphy products, special-teams coordinator Jerry Rosburg (linebacker coach at Cincinnati) and senior offensive assistant Craig Ver Steeg (a former Harvard quarterbacks and receivers coach, and recruiting coordinator). “We talk about ‘Murphisms,’” says Juszczyk. Such as? “The way he shakes your hand—he kind of tucks his elbows in, and not all his fingers are very straight and he comes in for a firm, tight handshake.”

For the entire extended Murphy network, the triple-bypass surgery in February 2014 was a jolt, especially because the workout-warrior coach is always in fighting trim. When he returned after a six-week convalescence, Murphy made one concession to his illness: “Last year was first year in 30 years I didn’t call plays.” Whatever works: The job he, Lamb, defensive coordinator Scott Larkee ’99, and the rest of the staff did was perhaps the most masterly of the Murphy regime, especially in view of injuries to key players such as starting quarterback Hempel. (Backup Scott Hoesch ’16 grittily stepped in to engineer six of the 10 wins.)

Martha Murphy thinks last November’s victory over Yale was her husband’s most satisfying, writing in an e-mail: “Considering that it was nine months post open-heart surgery, [the presence of] ESPN GameDay and national television, winning at home versus Yale, completing a perfect season and then to end our night having a wonderful family dinner in a quiet room in the Square was magical. A journey starting just nine short months [before] when my children and I were very concerned and to see how hard Tim and all the coaches and players worked to prevail and come back even stronger and have a perfect season.” Grace Murphy says her dad“takes time now, he absorbs more. Before surgery life was more compartmentalized for him, there was a time for work and a time for pleasure. Now he enjoys the incremental victories (on and off the field). Growing up we rarely went out to eat, and especially not during football season, but now we go out after many games and celebrate what has been achieved so far. It’s no longer about waiting till the end of the season after a victorious Yale game.”

* * *

Someday, Crimson supporters will have to sweat the end of the victorious Murphy era. Harvard will not reveal how long he is signed for. In the past, Murphy has had overtures from schools such as Indiana and Navy, and was even rumored to be under consideration at Penn State when the late Joe Paterno stepped down four years ago. Buddy Teevens says of any potential Murphy move, “He’s been very appreciative of Harvard. The Cincinnati experience gave him the full spectrum of the good, the bad, and the ugly. People have taken a run at him, but it would have to have been very special. And he would take a look, but he’d step back and say, [Harvard] is a very special place.”

Then again, the man has been known to pull off some magnificent fakes.