Among the reasons why the United States might be considered exceptional, there’s one that puts it in unexpected company: along with China, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, it ranks as one of the world’s top executioners. Because most countries have abolished capital punishment, the U.S. retention of the death penalty is anomalous, especially among Western, industrialized nations. What explains this difference?

“The death penalty, in the larger scheme of history, is normal,” writes Moshik Temkin, associate professor of public policy at the Kennedy School. Rather than ask why capital punishment still exists, he suggests, look at history from a different angle: given abolition’s rapid spread among other democratic countries, why has it failed to take hold in the United States? His recent paper, “The Great Divergence,” takes a transatlantic approach, comparing France—a relative newcomer to abolition, in 1981—to America.

In France, the end of the death penalty resulted from a top-down political process. Robert Badinter, a criminal-justice lawyer nicknamed “Monsieur Abolition” for his activism, convinced Socialist Party leader François Mitterand to take up the cause in the lead-up to the 1981 presidential election. Once victorious, Mitterand named Badinter minister of justice, and within five months pushed a successful vote on the issue through the legislature. Abolition was “contingent on the actions of a select few elites on the political left,” writes Temkin, who notes that the death penalty enjoyed wide popular support among the French people and the media. These select elites framed the vote as a matter of principle rather than policy: as a choice about what to do with the worst criminals—those whose guilt was undoubted, who committed horrific crimes, and who showed no signs of repentance or rehabilitation. Subsequently, abolition was solidified when France signed international treaties that framed capital punishment as a human-rights violation. Today, abolition is a precondition for entering the European Union—and, Temkin says, because secession from that body seems “unthinkable,” that forecloses any possibility of the death penalty’s return.

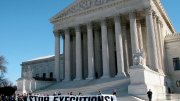

But Americans are reluctant to relinquish national sovereignty under international agreements, he says, and “don’t use the language of human rights to analyze our own politics.” Instead, they tend to think about the death penalty in civil-rights or constitutional terms. National decision-making about this matter, Temkin explains, “has been handed over, collectively, to the Supreme Court.” Opponents have attacked capital punishment at its weakest legal points, while supporting state-by-state abolition. Beyond a brief moratorium on executions in the 1970s, the lasting result has been regulation and restriction. In a series of decisions between 2002 and 2008, the Court ruled that juvenile offenders, people with certain intellectual disabilities, and those convicted of non-murder offenses could not be put to death. These developments have convinced some observers that the death penalty itself will soon be declared unconstitutional, but Temkin remains skeptical. “My argument, based on the history, is that this is not a track that leads to the sort of permanent abolition we see in other parts of the world.”

“Abolition, as a cause, doesn’t have a champion.”

American arguments against the death penalty tend to be procedural, focusing on breakdowns in the criminal justice system: racial disparities, botched executions, exonerations due to DNA evidence, and the high cost. Abolitionists do not think moral arguments will be politically effective, Temkin reports, so “What they want to do is bring down the number of people executed to as close to zero as possible. And that’s a very pragmatic approach.”

But such “reformist” arguments cannot lead to lasting abolition, he argues. “In a similar way, ” he writes, “anti-slavery activists of the antebellum era could not be considered abolitionists if they claimed that slavery was inefficient, randomly applied, brutal, and racially discriminatory, but neglected to mention that as a matter of principle it was immoral for one man to own another man as property.”

Today, he says, the death penalty is “the orphan in political life,” lacking a grassroots movement to pressure politicians: “Abolition, as a cause, doesn’t have a champion.” The public revisits the issue occasionally—often when there’s a high-profile, controversial execution—but not since the 1988 presidential race between George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis has the question been debated in the national political arena.

Late October brought a brief flurry of interest. The editor-in-chief of the Marshall Project, a news nonprofit focused on criminal justice, opened an interview with President Obama by asking point blank whether he opposed capital punishment. “I have not traditionally been opposed to the death penalty in theory, but in practice it’s deeply troubling,” the president answered. Later that week, a New Hampshire voter asked presidential candidate Hillary Clinton her opinion on abolition—she opposes it—leading rival Democrats to declare their own views, in favor. Still, public attention has centered mostly on the Supreme Court; its current docket includes a number of death-penalty-related cases.

Yet capital punishment should be regarded fundamentally as a political matter, not solely the purview of legal experts, Temkin argues; it’s a question grounded in the relationship between people and their government, and the power government is authorized to wield over an individual. “Whatever one thinks of the death penalty,” he says, “I do think that if you’re an American, you should probably think it belongs in the public conversation—and not just in the New York Times op-ed pages. It’s a topic that belongs to everybody.”