At the turn of the twenty-first century, the United States was trying to come to grips with a serious education crisis. The country was lagging behind its international peers, and a many-decade effort to erode racial disparities in school achievement had made little headway. Many people expected action from the federal government.

George W. Bush and Barack Obama successively took up the challenge. For all their differences on how best to stimulate economic growth, secure the national defense, and fix the health-care conundrum, the two presidents shared a surprisingly common approach to school reform: both preferred the regulatory strategy. In 2001, Bush persuaded Congress to pass a new law, No Child Left Behind (NCLB), creating the nation’s first test-based federal regulatory regime in education. When NCLB ran into trouble, Obama kept the tests but invented new ways of extending the top-down approach. Unfortunately, neither president’s program came close to closing racial gaps or lifting student achievement to international levels.

The Obama administration is now packing up and heading home, leaving the regulatory machine in ruins. A new law, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), passed by an overwhelming bipartisan majority in Congress, has unraveled most of the federal red tape. Although the mandate for student testing continues, the use of the tests is now a state and local matter. School districts and teachers’ unions are rubbing their hands at the prospect of reasserting local control.

Charter schools are beginning to pose genuine competition to public schools, which show little capacity to improve on their own.

With districts beset by collective-bargaining agreements, organized special interests, and state requirements, choice and competition remain the main levers of reform. Vouchers and tax credits are slowly broadening their legal footing. Charter schools are growing in number, improving in quality, and beginning to pose genuine competition to public schools—especially within big cities. Introducing such competition is the best hope for American schools, because today’s public schools show little capacity to improve on their own.

From Jawboning to Regulation

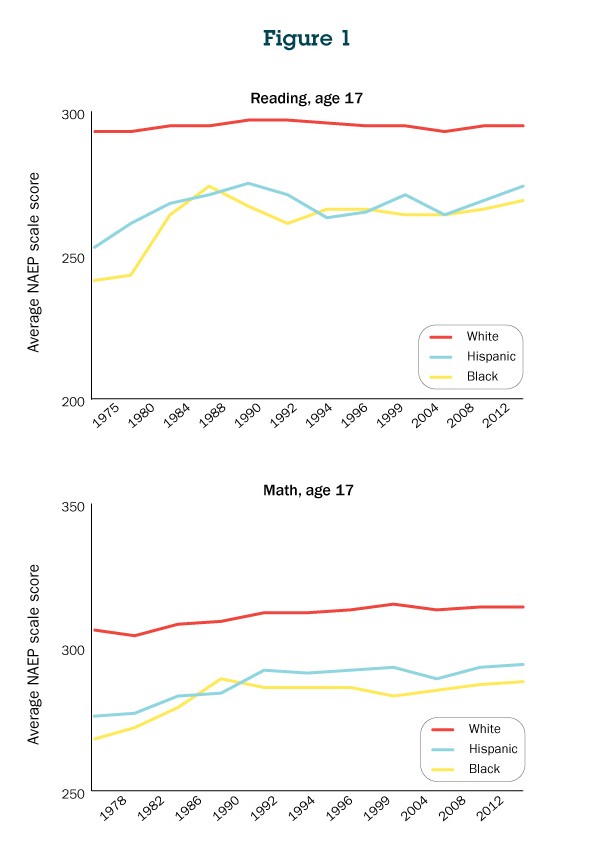

A bit of history. When presidents first tried to fix the schools, they relied strictly upon persuasion, resorting to the “bully pulpit” to bend the recalcitrant to their desires. Two years into the presidency of Ronald Reagan, the National Commission on Excellence in Education issued a report, “A Nation at Risk,” highlighting the low and declining performance of U.S. students. The report mobilized reform efforts in states and school districts across the country without any new federal regulatory framework. SAT scores, which had trended downward, now reversed direction. The reading scores of African-American 17-year-olds on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) leaped—a gain equivalent to roughly two to three years of learning (see figure 1). But in the 1990s, blacks’ scores slipped backwards, leaving the racial gap in 2012 larger than the one in 1988.

In an attempt to reverse the trend, George W. Bush tried to channel Reagan by constructing “compassionate conservative” messages that insisted no child be “left behind.” But his oratory inspired little enthusiasm among either students or educators, perhaps because of the close, controversial election of 2000. Expectations for Obama were greater. Young people, especially within the African-American community, had flocked to support his campaign, but the president gave priority to his economic stimulus and healthcare redesign, leaving him with little leverage for K-12 education reform. Early in his tenure, Obama pointed out that “leadership tomorrow depends on how we educate our students today, especially in math, science, technology, and engineering.” Yet even that restrained language disappeared as his term wore on. By the time of his final State of the Union address in January 2016, he had nothing to say about K–12, other than to mislead the public into a false sense of well-being: “Today, our younger students have earned the highest math and reading scores on record. Our high-school graduation rate has hit an all-time high.” The rosy proclamation obscured the fact that few gains had been registered and racial achievement gaps were nearly as wide as when he entered the White House.

By the time the presidents vacated the bully pulpit, the billfold was barely opened. The Bush administration was reluctant to “throw more money at the problem” of educational disparities, though it agreed to some additional spending as the price for securing NCLB’s enactment. During Bush’s administration, federal expenditures edged upward from 10 percent to 11 percent of total spending on K-12 education (with the remainder of the costs shared about equally by state and local governments). When President Obama took office, it initially seemed that he would dramatically alter the federal fiscal role. With an overwhelming Democratic majority in Congress, he secured passage of a trillion-dollar economic stimulus package that included more than $100 billion for K-12 education. The new money was to be spent over a two-year period, with some of it devoted to compensatory education or special education, the rest to district priorities. Federal aid to K-12 and preschool education jumped from $39 billion in 2008 to a high of $73 billion in fiscal year 2010 (0.49 percent of Gross Domestic Product). The following year, $66 billion in federal funding continued to flow. Much of the aid targeted urban districts with heavy concentrations of low-income and special-education populations. Local school districts briefly enjoyed a generous flow of federal cash.

Ironically, the federal dollars arrived before the recession-induced fiscal crunch hit property-tax revenues (the principal form of local school financing), as it takes a year or two, sometimes longer, for depressed property to be assessed at its new, lower value. But the federal dollars had to be spent immediately, in the administration’s view, and local expenditures could not be reduced. As a result, per-pupil expenditures for current education operations reached a near all-time high in the recession school year of 2008-09, climbing (in constant dollars) to $12,302 from $10,890 in 2001-02, an increment of 13 percent over that seven-year period.

The education industry hoped and expected the stimulus package would set a new floor for federal expenditure. But the 2010 election overturned that assumption, as the newly elected Republican majority in the House of Representatives reduced federal funding. Federal aid to preschool and K-12 education dropped steadily—to just $41 billion in 2014 (0.24 percent of GDP): less than in the last year of the Bush administration. State and local governments could not—or would not—make up the difference. Expenditures per pupil (in constant dollars) slid to $11,732 in 2011-12, the latest school year for which data are available, a decline of nearly 5 percent over that three-year period. For big cities, the cuts were much larger.

Regulation to the Rescue

Short on both rhetoric and ready cash, the presidents turned to regulation. The effort was bipartisan from the beginning. Putting aside the differences sparked by the nail-biting 2000 presidential contest, Senator Edward Kennedy and President Bush worked together to persuade their party colleagues to pass NCLB. Signed into law in January 2002, the law required annual statewide tests in grades 3 through 8, and again in high school. Every state was asked to set proficiency standards toward which students had to make adequate progress each year until all students had crossed that bar in 2014. If students were not making the requisite progress, families would have the option of picking another public school within the district. If that didn’t work, students were to have access to afterschool study programs. And if that failed, schools were to be reconstituted under new leadership.

All these steps required numerous regulations. But school districts found ways of undermining federal objectives. They instituted byzantine procedures that parents had to navigate before they could exercise choice. Reconstitution of low-performing schools often consisted mostly of window dressing.

Nonetheless, NCLB did shine a spotlight on the public schools. If schools failed to make adequate progress, officials had to explain themselves to reporters, parents, and the public at large. As the goal was to make all students proficient by 2014, the explanations proliferated with each passing year.

That utopian 2014 objective was never meant to be taken seriously. NCLB, like many other federal laws, had a five-year expiration date, and it was generally assumed that new legislation would be on the books by 2007, long before the full-proficiency deadline was reached. But Congress became deadlocked, so legislators simply extended NCLB from one year to the next, a necessary step if federal funds were to continue flowing to the states. Not until December 2015—eight years past the deadline for new legislation—did Congress replace NCLB with ESSA.

In the meantime, the absurdities in NCLB were becoming increasingly apparent. With nearly every school failing to bring all students up to full proficiency, nearly every school was theoretically at risk of reconstitution. Criticisms of NCLB escalated—and many were justified. The definition of “failing schools,” for instance, unfairly picked on those serving disadvantaged students. But the critiques quickly degenerated into blanket attacks on all standardized tests: “The tide on testing is turning,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, who then called for NCLB revisions that would “address the root cause of test fixation.” Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, averring that testing was “sucking the oxygen out of the room,” promised to do something about it.

Race to the Top

Illustration by Adam Niklewicz

Initially, the Obama Administration attempted to sustain the overall policy by cutting back on most of the detailed regulations, even while keeping annual student testing. In what at first appeared to be a brilliant maneuver, Duncan in 2009announced “Race to the Top” (RttT), a competitive-grants program that had been authorized and funded by the trillion-dollar stimulus package. The money for RttT, $4 billion, was but a tidbit within the package, amounting to less than two-tenths of 1 percent of U.S. school expenditures. Yet the idea of a competition among states for a fixed sum of money captured public attention. RttT’s purpose, the president said, was to “incentivize excellence and spur reform and launch a race to the top in America’s public schools.” RttT encouraged applicants to propose a broad range of innovations, including policies akin to Common Core State Standards being proposed by the National Governors Association, among others. States were also encouraged to design plans that would evaluate teachers, in part on their students’ test scores. Most states entered the competition, and 18 states and the District of Columbia won awards, ranging from $17 million to $700 million—sums insignificant in themselves but highly prized for the praise received for winning a grant.

The competition proved so successful the U.S. Department of Education relied upon its framework for an even bolder policy: states could seek a waiver of the most onerous NCLB requirements by submitting alternative reform plans similar to those encouraged by RttT. Eventually, 43 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico were granted such waivers, in effect gutting the federal law.

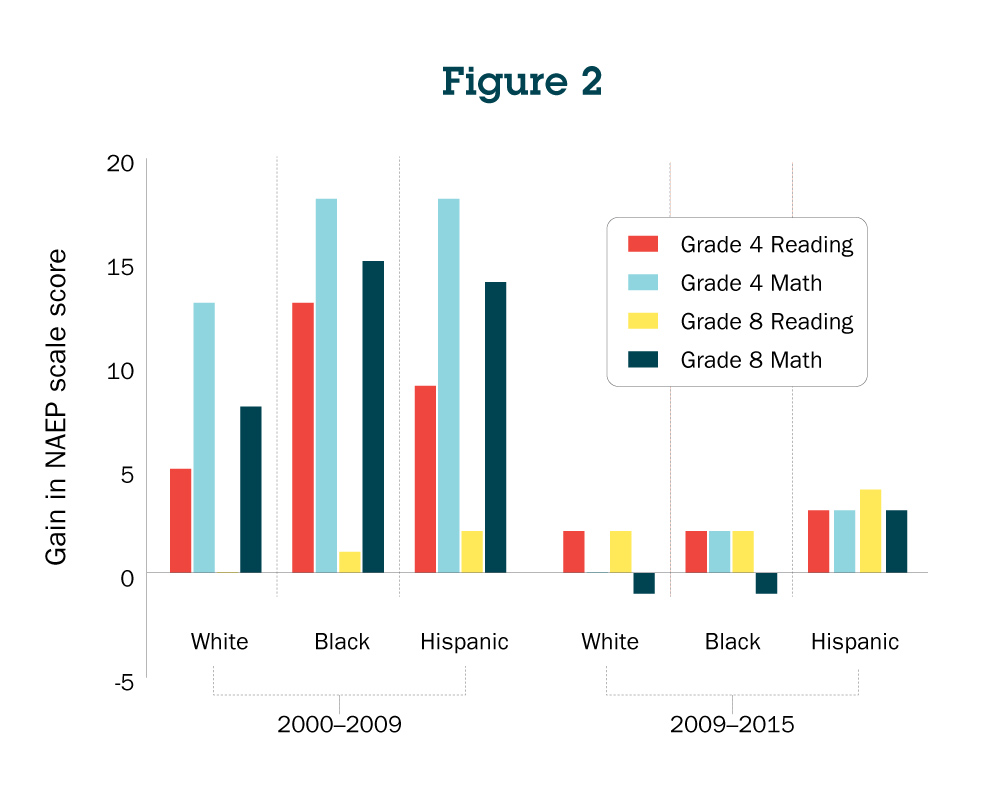

RttT and the waiver policies it engendered must therefore be counted as extraordinary political successes if only because they allowed the Obama administration to substitute its priorities for those of its predecessor. But as the University of Virginia’s late scholar of federalism Martha Derthick, Ph.D. ’62, wrote at the time, waivers “undermine the rule of law,” raising “a concern that extends well beyond the field of education.” Secretary Duncan had left himself badly exposed by constructing an education policy on a series of questionable administrative maneuvers rather than a solid legislative footing. Political opposition began to rise against two of the waivers’ key recommendations: establishing higher state standards and tightening teacher evaluations. Tea Party activists objected to what the Heritage Foundation called the administration’s intent to nationalize “the content taught in every public school across America.” And teachers’ unions balked at unfair evaluations of teacher performance. “Old tests are being given, but new and different standards are being taught,” National Education Association president Dennis Van Roekel declared. “This is not ‘accountability’—it’s malpractice.” Meanwhile, student progress on NAEP tests came to a virtual standstill, leaving regulation with hardly a substantive leg on which to stand (figure 2).

Caught in the maelstrom, the administration was unable to defend against the enactment of ESSA, which upset nearly all the federal regulatory reforms of the prior 15 years. The new law requires annual testing—but leaves it to the states to decide how the results will be used—and removes any federal role in setting standards or teacher evaluation requirements as well as most other regulations, shifting authority over schools back to states and localities. As an education-reform strategy, federal regulation is dead. Nor is there much appetite among the states for asserting new accountability rules. The regulated captured the regulators. If reform is to proceed now, it will happen because more competition is being introduced into the American education system.

Catalyzing Competition

Creating a system of competition among educational providers in the hope that it will improve student performance is no easy task. The political process is bound to be slow, arduous, disruptive, upsetting, and divisive. Defenders of the status quo will argue that some indefinable essence is lost if anyone other than a government agency operates a school, no matter how segregated the homogeneous neighborhoods are that form the school’s attendance boundaries. Quite apart from the substantive debate, the politics is messy at best, disastrous at worst. The winning schools are ingrates who almost always feel they deserve any benefits they enjoy. Losers can hardly be faulted for blaming not themselves but changes in the rules of the game. But the long-term consequences of greater competition within an industry for consumers and society as a whole can be highly beneficial, as deregulation of the airlines and telecommunications industries has shown. Comparable gains have yet to appear throughout American K-12 education, but to see how it might happen, consider the slow growth of choice and competition—via vouchers and charter schools—that has taken place during the past quarter-century.

• Vouchers. Milton Friedman made the case for choice and competition in his seminal 1955 article on school vouchers, writing:

[School choice] would bring a healthy increase in the variety of educational institutions available and in competition among them. Private initiative and enterprise would quicken the pace of progress in this area as it has in so many others. Government would serve its proper function of improving the operation of the invisible hand without substituting the dead hand of bureaucracy.

It was another 35 years before Wisconsin enacted a voucher program for the city of Milwaukee. Since then, another 28 states have legislated some kind of voucher program, tax credit, education savings account, or other intervention that provides government aid to students attending private schools. None of these programs are at scale, however: nationwide, less than 1 percent of the school-age population is participating. Yet careful studies show that voucher students of minority background, even if they do not perform much better on standardized tests than their peers in public school, are more likely to graduate from high school and go on to college. Apparently, private schools seem to do better at fostering character and grit than academic instruction per se.

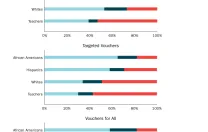

Vouchers command majority backing within minority communities, both black and Hispanic. Whites are less enthusiastic: only one-third of them support income-targeted vouchers.

Perhaps this is why vouchers command majority backing within minority communities, both black and Hispanic. Whites are less enthusiastic: only one-third of them support income-targeted vouchers, though support for and opposition to universal vouchers is more or less evenly divided.

The strongest opposition comes from teachers and the unions that represent them. Al Shanker, the brilliant (if controversial) leader of union efforts to win collective-bargaining rights in New York City, denounced the idea: “Without public education, there would be no America as we know it,” he cried. Vouchers for the poor would be “merely the nose of the camel in the tent.” School boards and teachers themselves could not have agreed more.

• Charters. Union opposition to vouchers was so intense that it opened the way for another choice reform: charter schools. When first enacted in Minnesota in 1989, charters appeared to be nothing more than a safe place for teachers to try out new ideas that public schools could adopt. Shanker himself initially endorsed charters, making it difficult for subsequent union leaders to express unconditional opposition. Unions nonetheless resist charter growth because the schools are run by nonprofit organizations rather than the government; they are free from many state regulations; and they are usually not subject to collective-bargaining agreements. Yet charters can claim that they are in fact public schools. They are authorized by a government agency (a state department of education, state university, mayor’s office, or local school district). Their operating funds come primarily from government sources. Their educational mission is secular. When parental demand for a charter school exceeds available space, the school typically holds a lottery in order to choose impartially among the applicants.

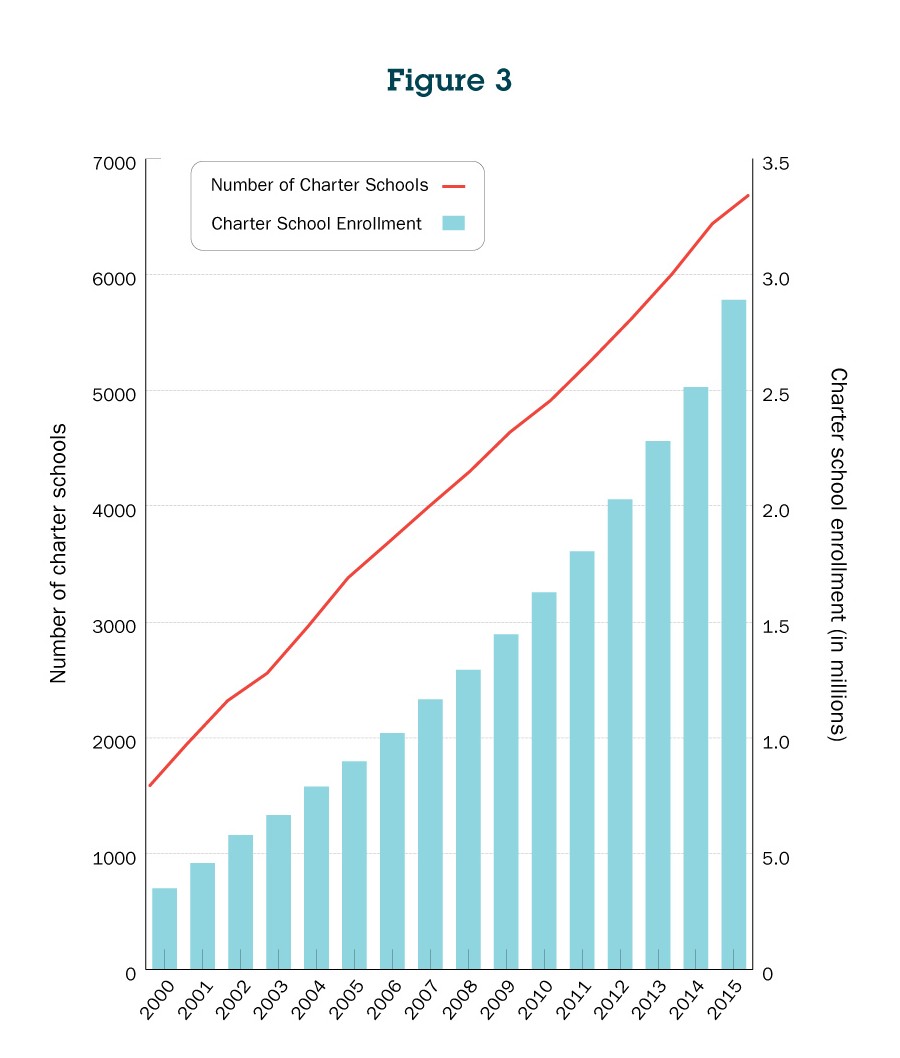

Charters regularly win endorsements from Democratic and Republican leaders alike, and the movement has enjoyed steady, if unremarkable, growth. Forty-three states allow the authorization of charters; more than 6,000 charter schools have been established; and nearly three million children now attend them (figure 3). As their numbers grow, charters are beginning to disrupt the status quo more than vouchers.

Admittedly, charter schools have had difficulty penetrating rural and suburban communities. There, a public school, no matter its quality, is perceived as a valuable community institution. In suburban areas, charters often sport progressive pedagogies that yield poor testing performances compared to traditional public schools. Moreover, school choice already exists for those who have the resources and resourcefulness to live in suburbs that offer better schools. The affluent already have the options they need.

A different story emerges from central cities. Big-city public schools are in big-time trouble, and many families send their children to their local school more out of necessity than choice. For these families, the charter-school option often holds strong appeal. Compared to district schools, the charters are generally perceived to be smaller, safer, friendlier, and, more often than not, a better place to learn. In contrast to charters in suburban areas, central-city charters typically embrace the “no-excuses” model of teaching and learning: strict dress codes, rigorous discipline, extended school days and years, and high expectations for performance on standardized tests. Though critics complain that these schools are too restrictive, studies regularly reveal they are outperforming their traditional public-school counterparts. The charter advantage seems to be particularly striking for African-American students from low-income families.

The charter-school movement has benefited from the spectacular results achieved by the Harlem Children’s Zone Promise Academies, Success Academy, BASIS Schools, KIPP Schools, Uncommon Schools, and others in New York City, Boston, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Washington, D.C., and other prominent cities. Led by strong entrepreneurs, staffed by high-quality teachers from selective colleges, financed by local donors and major foundations, these institutions are providing rigorous instruction over an extended school day and year. Their ability to lift students who come from low-income, single-parent families to a high level of performance that prepares them for college has shed a warm glow over the entire charter-school undertaking. In 16 cities, more than 25 percent of public-school students are enrolled in charter schools. In New Orleans, the percentage is no less than 79 percent; in Detroit, 51 percent; in the District of Columbia, 43 percent; and in Philadelphia, 28 percent. In Los Angeles, Boston, New York City, Chicago, and elsewhere, enrollments would be much higher were the supply not artificially constrained by state laws limiting charter growth. According to the scholarly journal Education Next’s2015 poll, supporters of charters outnumber opponents by a two-to-one margin, both among the public at large and in minority communities. However, a majority of teachers oppose the innovation (see sidebar, opposite).

Will the competition between charters and standard, district-operated public schools intensify in the next decade? Is this competition the new reform wave that will sweep over American education? Is there a tipping point at which the demand for charters will force a reconstruction of the educational system more generally? Several factors point in that direction:

- Many charters in urban areas are oversubscribed.

- Big-city school districts must spend a large share of their budgets for employee healthcare benefits and pensions, secured by expensive collective-bargaining agreements—a problem charters have escaped thus far.

- Charter-school parents can be mobilized in numbers when political confrontations occur.

- Student performance at charter schools is showing signs of improvement over time (mainly because of the closing of weak charter schools).

These are straws in the wind, but it is still too soon to predict confidently the degree to which choice will be introduced into American education during the next decade. Teachers’ unions are mobilizing to block charter expansion in state legislatures and through collective bargaining with local districts. Nor is there much support for charters in suburbia, small towns, or rural America. If charters achieve a breakthrough, it will be in the country’s largest cities. Spreading out from that base will be a slow, arduous process—and then only if charters demonstrate that they can deliver a superior educational experience.

If the future of charter schools remains uncertain, the same cannot be said for top-down regulation. Unless teachers surprise us all by embracing a new curriculum generated by Common Core State Standards, and that curriculum motivates students to higher levels of performance, reforming the system from within is unlikely to succeed. If school reform is to move forward, it will occur via new forms of competition—whether vouchers, charters, home schooling, digital learning, or the transformation of district schools into decentralized, autonomous units. And if student testing has an impact on reform, it will be due to the better information parents receive about the amount of learning taking place at each school. The Bush-Obama era of reform via federal regulation has come to an end.