A hundred years ago, at the height of World War I, the Battle of the Somme raged in northern France. More than 600,000 British and French troops became casualties trying to break the German lines, yet an American became arguably as celebrated as any of them, even though his nation had not yet entered the war. A few weeks before he was killed, Alan Seeger, A.B. 1910—a tall, mop-haired French Foreign Legionnaire—composed an eerie, premonitory three-stanza poem. Either despite or because of its brevity, “I Have a Rendezvous with Death” was an instant classic—the most famous American poem of a verse-filled war. It became not only a staple of high-school English-class recitations but also the favorite poem of President John F. Kennedy ’40.

Seeger’s death wish was not lifelong. His early days were spent happily on Staten Island. When he was 10, the family began two years in Mexico, where his father had business interests; that country, with its exotic flora, figured in many of his later poems.

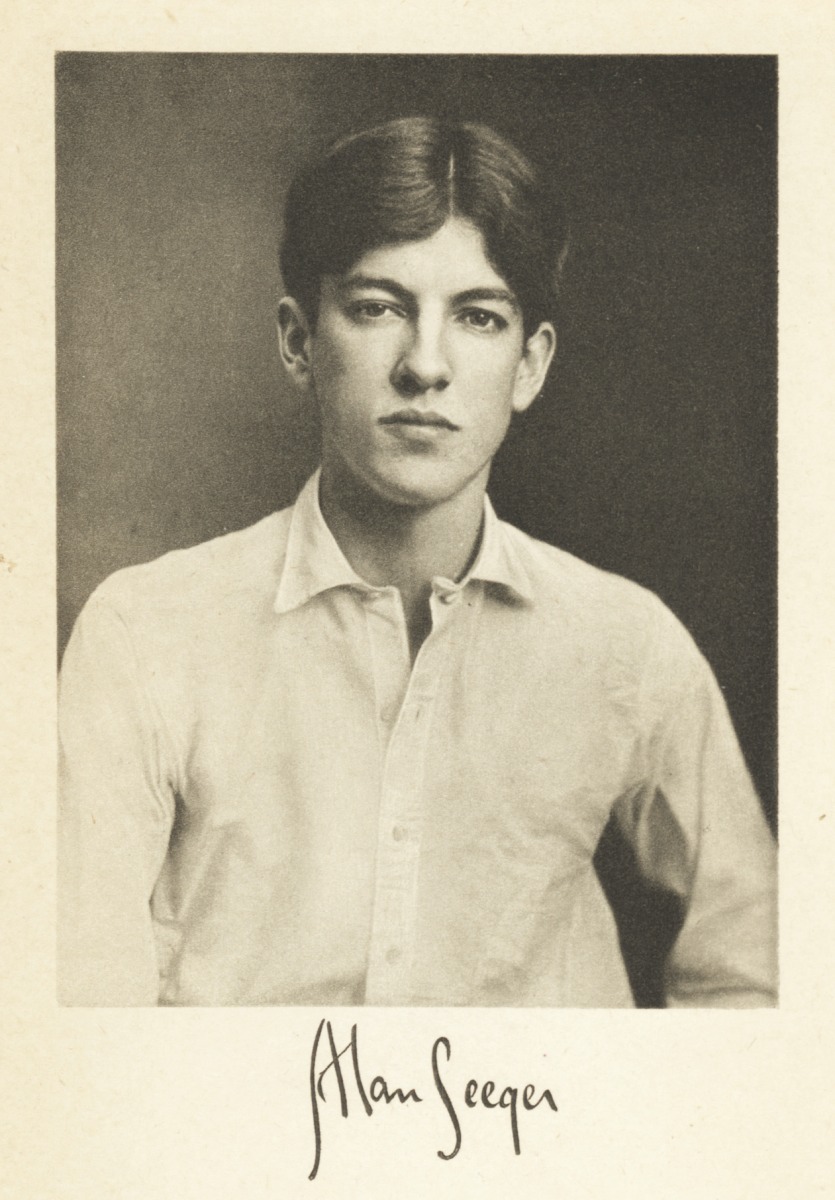

The poet as a senior at Harvard

At Harvard, he took a while to find his footing. Recalling those days a decade later, in a letter from the front to an old friend, he wrote: “My life during those years was intellectual to the exclusion of almost everything else. I shut myself off completely from the life of the University. I felt no need of comradeship.” He was more social as an upperclassman, earnestly composing poetry (heavy on truth and beauty) and finding a congenial group of fellow aesthetes (including classmates Walter Lippmann and John Reed) as an editor of the literary magazine The Harvard Monthly.

These years may have launched him, at least literarily, on his rendezvous with death. In Memoirs of the Harvard Dead in the War Against Germany (1920), the entry for Seeger notes: “In The Advance of English Poetry in the Twentieth Century, by Professor Phelps of Yale, there is quoted a letter from Professor Robinson of Harvard telling of the strong impression made upon Seeger by the Irish ‘Song of Fothad Canainne,’…a song which sings: ‘It is a blindness for one who makes a tryst to set aside the tryst with death.’ ”

After graduation, Seeger aimed to become a full-time man of letters—first in New York City, then in Paris. The market for aspiring poets was no better then than now, but in the City of Lights, Seeger “was happier than he had ever been before,” recalled another Monthly colleague, poet John Hall Wheelock, A.B. 1908. But “he was still uncertain of himself and his aims, still waiting for that destiny which he felt every day more clearly and steadfastly was somehow in preparation for him.”

The guns of August 1914 announced his path: 23 days after the outbreak of war, Seeger enlisted in the Foreign Legion. Like many who rushed to the colors, he envisioned a brief, glorious conflict he would survive. On October 17, from training camp at Aube, he wrote his mother: “Do not worry, for the chances are small of not returning and I think you can count on seeing me…next summer.”

Soldiering proved no less Seeger’s metier than sonnetry. In the next two years he was shuttled from trench to trench, in harm’s way from German artillery and bullets, one of which “just grazed my arm, tore the sleeve of my capote and raised a lump on the biceps which is still sore, but the skin was not broken and the wound was not serious enough to make me leave the ranks.” In October 1915 he was mistakenly reported killed in the Battle of Champagne.

All along, he was writing—poems, sonnets, a diary, and picturesque letters as well dispatches to U.S. newspapers. In spring 1916, he composed the eloquent “Ode in Memory of the American Volunteers Fallen for France”; he was bitterly disappointed when he didn’t receive leave to read it in Paris on Decoration Day.

On July 4, three days after the start of the Somme offensive, Seeger’s battalion was ordered to capture the village of Belloy-en-Santerre. The first wave went forward, Seeger’s reserve company following. A friend and fellow legionnaire, an Egyptian named Rif Baer, chronicled his final moments. “His tall silhouette stood out on the green of the cornfield,” Baer wrote. “…His head erect, and pride in his eye, I saw him running forward, with bayonet fixed. Soon he disappeared and that was the last time I saw my friend.” Twelve days before, Seeger had turned 28.

As is often true for artists, death was (to be blunt) a good career move for Seeger, especially after the United States entered the war. Scribner’s published a collection of his poems, and his diary. The New York Times Sunday Magazine ran an admiring profile. Sportswriting icon Grantland Rice lionized him in verse in Songs of the Stalwart.

Later critics, including a fellow soldier, Paul Fussell, Ph.D. ’52, have been more jaundiced. In his groundbreaking The Great War and Modern Memory, Fussell dismisses “Rendezvous,” all but labeling it second-rate, especially beside contemporary British war poetry: “It is unresonant and inadequate for irony compared with works like…[Wilfred] Owen’s ‘Exposure,’ which begins with a travesty-echo of the first line of Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale.’ ” Unfortunately, Fussell does not mention Seeger’s “Ode in Memory,” a work of honest sentiment, historical sweep, and considerable elegance.

Seeger had asked that weeping be tempered at his death. A year before, he wrote: “The tears for those who take part in [battle and] …do not return should be sweetened by the sense that their death was the death which beyond all others they would have chosen for themselves, that they went to it smiling and without regret.”