Editors' note: Arthur Schott Lopes ’19, a classics concentrator, served as an undergraduate fellow during the preparations for the Houghton Library’s seventy-fifth anniversary exhibition, covered in “An ‘Enchanted Palace,’” in the March-April 2017 issue. We asked him to share his experiences as a College student delving into the library’s collections.

Until the 1990s, Houghton Library’s outer doors were made of steel. They made the building feel like Harvard’s Fort Knox, an impenetrable place open to only the select few. The rare books and manuscripts library was, then, a place where undergraduates did not often tread.

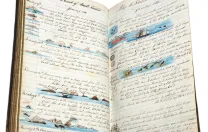

I entered Houghton for the first time on a chilly December morning, for a class during my freshman year. Nothing prepared me for what I saw that day: papyri, illuminated manuscripts, an original copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio, T.S. Eliot’s copy of Dante’s Commedia. It’s easy to underestimate libraries when so much knowledge is readily accessible, but Houghton showed me that a lot of precious information has yet to go online, and that we still need human help to find it. My experience there also made clear the importance of learning how to research. Susan Halpert, who has been a reference librarian at Houghton for 36 years, maintains that mastering that skill gives a student “access to possibility.” She also affirms the importance of the material aspect of the collection in our increasingly virtual world: at Houghton, she says, there is “amazement at the physicality of things,” and respect for the vital importance of the objects’ format as well as their content. The Houghton archive is a testament not only to knowledge, but also to its transmission through the ages.

Soon after that first visit, I began brainstorming ideas to apply to the library’s Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program (SHARP) fellowship, which supports students pursuing independent projects related to its collections. Talking to my friends about the library, though, was frustrating. Most were not even aware of Houghton’s existence. On our first day at Harvard, we all got a copy of the 49 Book, an advising resource that introduces students to all of the College’s concentrations. Maybe that was what Houghton needed—a guide where students could look for their concentration and discover at least a fraction of the library holdings that could be useful in their chosen field.

Once I began the fellowship, my first challenge was how to appeal to the entire undergraduate student body. Houghton’s forte is its humanities collections—and many in those disciplines had at least heard of the library. What about students in the social sciences, the sciences, and engineering? Did Houghton have materials to entice them? Among the library’s treasures are Maria Sibylla Merian’s impressive 1705 treatise Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, a key work in the field of entomology; a series of original editions of Alexander Graham Bell’s diagrammatic pamphlets about electricity and its uses; Massachusetts meteorological records containing more than a century of weather data; and Charles Darwin’s manuscript copy of a section of his Origin of Species. Taken together, these materials could serve interests in history and science, evolutionary biology, environmental science and public policy, and more.

Another mission I took on during the summer was to highlight the sociocultural diversity of Houghton’s collections. Though the library was founded to house the treasures of Western civilization, it has collected materials beyond those bounds. Among the items I was able to include are American slave-sale bills; comics featuring black superheroes; a mass-produced Chinese alarm clock featuring Mao’s face; Zoroastrian liturgical texts; and some of the letters of Julia Ward Howe and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The library is also seeking to expand its holdings. Leslie Morris, curator of modern books and manuscripts, has spearheaded the effort to acquire materials related to the Latinx community, for instance, and Houghton has tried to keep pace with current social movements, collecting signs and posters related to Occupy Harvard and the Women’s March as the protests occurred.

Houghton’s forbidding steel front doors are now made of glass. As its physical space has become more welcoming, its collection has become more capacious, even overwhelming. While it’s by no means a comprehensive catalog, I hope my guide, COMPASS, offers my peers a beautiful “access to possibility” and that it will serve as a pointer empowering them to explore.