Fifty years ago this week, they were just touching down in Bombay, having made their way through the southern islands of the Philippines after a flight from Hong Kong a couple of weeks earlier: 88 undergraduate singers, some as young as 17 and none older than 22, all of them halfway around the world from home for the longest time they’d ever been away. They were members of the Harvard Glee Club and the Radcliffe Choral Society, on a summer concert expedition mostly in Asia. The Asian Tour, it was called, those words printed in block letters across the crimson-bound itinerary books they all carried.

But the name would become shorthand for so much more than that. For something that the singers, even now, can’t fully articulate, and yet it’s kept them coming back to each other again and again, for decades. Every five years, the group reconvenes in Cambridge to sing together and resurface old memories and mark the years and lives that have unspooled around them—and to remember those they have lost. There are long, talky lunches and impromptu sing-alongs and two-hour rehearsals that bring them crisply to their feet in the old familiar semicircular rows, their black folders of sheet music opening and closing together, their voices rising and falling.

This year’s reunion, their fiftieth, had been on their minds for a while.

Mansions to dirt floors

As much as it is anyone’s, the Asian Tour belongs to Ned Goodhue. As a freshman member of the Glee Club in the fall of 1963, he watched the upperclassmen prepare for a two-week tour of Canada and decided to organize his own concert trip, one that would last a whole summer. He brought the idea to Elliot Forbes, the legendary longtime conductor of the Glee Club and the Choral Society, who instructed that Goodhue’s tour must include Radcliffe and then said, “Keep me posted.” That was all the go-ahead Goodhue needed.

Casting about for destinations after concluding that a tour of the Soviet Union, his original idea, might be “a bridge too far,” Goodhue happened across the name of a particularly enthusiastic—and prominent—alumnus in Manila. Benito Legarda Jr., Ph.D. ’55, was an economist and historian, a rising executive at the Central Bank of the Philippines—and president of the local Harvard club. Goodhue got in touch. Immediately, Legarda was on board. A great idea, he declared. How could he help?

From that kernel, the itinerary began to build, country by country: Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, India, Israel, plus a few final days in Yugoslavia and Scotland. Goodhue ’68, M.B.A ’70, D.B.A. ’84, took a year off school in order to work on the tour plans full time, organizing the schedule, scouting travel routes and concert halls, flying overseas for meetings in American embassies and foreign governmental offices, reaching out to ask for help from Harvard alumni in each country. Forbes, meanwhile, set a vast, and challenging, musical repertoire: Josquin, Strauss, Brahms, Stravinsky, Haydn, Britten, Bach, Mozart, Bartok, Purcell, Lassus, plus Fair Harvard (of course) and folk songs from each country they would visit. The singers would perform 90 concerts in all.

A couple of weeks after spring semester ended in 1967, the group set off. Besides the 88 Glee Club and Choral Society singers who’d auditioned for the trip, there were Forbes and his wife, Kathleen, who sang alto, and three accompanists, including one who doubled as the tour physician and also sang first bass (Bernie Kreger, M.D. ’59, who still serves as the group’s accompanist at reunions). After a week of rehearsals in a secluded lodge in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park and two quick stopovers in Los Angeles and Honolulu, they boarded a flight bound for Tokyo.

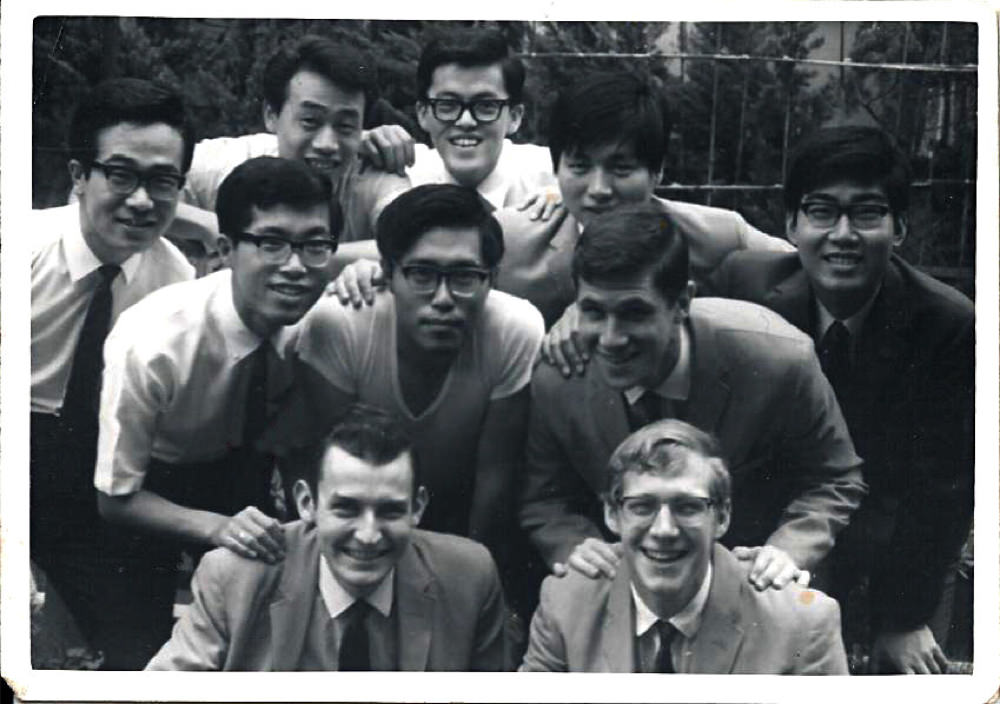

On the island of Jolo, in the southwest Philippines

Photograph by Peter Lovely '67

Laura Shapiro ’68 remembers looking out the airplane window and seeing rice paddies. That’s when it hit her just how far from home they all were. When you ask members of the Asian Tour today about their memories of the trip, these are the kinds of stories they tell. Throughout the tour, the students stayed not in hotels, but in local people’s homes—a purposeful, and, it turned out, profound decision that Goodhue made to deepen their cultural immersion (it also saved enough money to make the trip financially doable). Sometimes home stays meant a mansion, other times a dirt floor. In India, Kay Tolbert ’69 was put up on an estate with enormous gardens patrolled by peacocks; on one of the southern Philippine islands, she slept in a tiny house, sharing a bed with a Radcliffe classmate, “knowing that we’d uprooted whoever usually slept there.” In Ahmedabad, India, Ted Todd ’67 and Mike Epley ’67 stayed with the son of a Hindu sect leader whose followers revered him as the embodiment of a deity. They recall a trip to the temple with the son, a sweet, shy young man not much older than they were. With his father away, he was the one the monks and priests venerated, bowing down and reaching out to touch him—Todd and Epley recall the son’s seeming abashment as he excused himself to go to another part of the temple for a few moments to be worshipped.

Meanwhile, in Japan, tour president Steve Griffith ’67 bumbled through a hilariously calamitous bath that ended with his trying to dress himself in a kimono belt that he mistook for a full garment; the host father, with a look of horror, pointed out the kimono he hadn’t seen, immaculately pressed and folded nearby. (Griffith’s full account, and other stories from the 1967 tour, were recorded on video during the group’s 2012 reunion—the bath saga begins at 4:41 minutes in. Parts two and three of the recording are here and here.)

Shapiro remembers coming downstairs before 6 a.m. in Kyoto to find that her hostess, not knowing what Americans would eat, had prepared every kind of food she knew how to make. “She’d been up since Lord knows when, cooking.” Amid the feast of tempura, sushi, heaps of rice, and fresh-squeezed peach juice (“something I’ve never seen before or since”), she also served toast—just in case.

A few days earlier, in Tokyo, Shapiro and fellow singer Marilyn Wilt ’67 had been whisked away in a car by Japanese hosts who wanted to “show us something”—she and Wilt didn’t know what. After riding for what seemed like hours, they reached a hillside and stepped out of the car, following their hosts through a stand of trees that opened onto a tiny, exquisite building. Inside were arranged the objects for a Japanese tea ceremony. It was one of the most stunning things Shapiro had ever seen—the memory still amazes her. Gently, carefully, the hosts guided her and Wilt through the ceremony. “It was the most beautiful gift, and they wanted us to receive it, to see this about their country. It’s like, you’re just this tired, stupid American, and you get lifted up into a different world and set down in the most beautiful experience of Japan that anyone could ever have.… I wouldn’t have known how to ask for it. I wouldn’t have known it was there. They just handed it to us.”

In Japan.

All this hospitality just two decades after World War II ended. That fact struck Shapiro only years later, reflecting on the ardent farewell she’d received from a Japanese mother and daughter at the Tokyo train station as the singers were departing. Come back soon, they had told her in their limited English. “And 22 years earlier we had been bitterest enemies, feeding on caricatures of each other,” Shapiro says. “They were welcoming with their whole hearts this bunch of Americans. And we were never made to feel anything except warmly, graciously, lovingly welcomed. And of course we poured it all back a thousand-fold,” in the concerts they sang and the company they gave.

Israel was another climax. By that time, the singers had been traveling for two months and untold miles. They’d lost an engine over India and had to turn back briefly for another airplane. In Hong Kong, they’d arrived amid deadly riots against British colonial rule; the situation was so volatile they abandoned their home stays for the security of a hotel. Nearly every student had fallen sick at least once from food poisoning or exotic germs. But they kept singing, and they loved it, performing at sprawling auditoriums and city halls and village theaters and outdoor festivals, plus the occasional street corner.

In Jerusalem, the group sang near the Western Wall.

Photograph by Claire Max '68

The group landed in Jerusalem in mid August—eight weeks after the Six-Day War. “The place was almost still smoldering,” says Griffith. “There were ashes everywhere.” And euphoria. One of the first performing groups to come to Israel after the war, they sang at the Western Wall, which had just been captured by the Israelis. The repertoire included a folk song written as soon as the fighting ended; the U.S. embassy in Tel Aviv had forwarded the music while the singers were still in India. Forbes composed a choral harmony on the fly. When they sang in Jerusalem, the audience was in tears. Soldiers stationed backstage were crying, too. “It was incredible,” says Goodhue. “The Jews in our group got to pray at the Wall.”

A vanishing moment in time

In retrospect, says Goodhue, it’s remarkable that the tour happened at all. Though the Glee Club and the Choral Society had been touring internationally since the 1920s, they had never undertaken such a long trip—the students were gone for half of June and all of July and August. And the plans were extraordinarily intricate: travel, lodging, food, concert venues, visas, vaccines, multiple border crossings. The Boeing 707—the first commercially successful passenger jetliner, whose popularity ushered in the Jet Age—had been introduced only eight years earlier. Air travel was still relatively new—and expensive. “A round-trip economy airfare from Sydney to London was the equivalent to the total cost of a small house,” Goodhue says. “Almost even just the idea of being able to do this except for the very, very rich, was ridiculous. Ridiculous!” The Asian Tour’s entire budget was $126,000: local Harvard Clubs helped pay for in-country expenses, and singers’ families contributed about half of the total budget, chipping in however much they could. The other half came from donations, mainly from Glee Club and Choral Society alumni. (As part of this year’s fiftieth reunion, the singers raised $126,000 and presented it to the Harvard Choruses, to help fund future tours.)

More than that, though, says Goodhue, the Asian Tour occupied a vanishing moment in time. A decade later, the same trip would not have been possible. Places like Japan, Hong Kong, and India were not yet so modernized as they are today and were still relatively unknown to many in the West. By the late 1960s, the postwar American economy had been growing for 20 years straight. The Vietnam War and the draft loomed, and civil-rights struggles and antiwar protests roiled American public life, but despite all that, undergraduates from Harvard and Radcliffe—some naïve about politics, others very much aware—still looked forward to robust futures, Goodhue says, and “consequently, almost every student, regardless of their background, was curious about the world.” They could afford to be. And much of the world reciprocated.

When the students departed Cambridge on June 16, they knew they would be gone for two and a half months, and not just gone, but unreachable. “If you wanted to make an international phone call,” Goodhue says, “you had to book it several days in advance…Literally, in the world of the mid 1960s, you would come back from a summer trip to find out that your dog had died or your grandmother was sick or your brother was married.” During the trip, that isolation turned the singers both inward, toward each other and their music, and outward, toward the unknown, unimagined world they were traveling through.

“Everyone is accounted for”

The reunions started almost right away. The first one was in 1972. The singers, some barely graduated, came back together on campus to reprise their tour performances with a concert. Then about five years later, they came back again. And five years after that. “We didn’t choose ourselves as social friends in 1967,” says Griffith. “We were chosen to be singers.” But on the road in Japan and India and the Philippines (where they were chaperoned on a coast-guard vessel to avoid guerillas in the southern islands), a bond took hold. Friendship might not even be the right word: “It would be putting on airs to say we are all bosom buddies,” Griffith says, though the tour yielded many close relationships and at least three marriages. The singers had seen the world together. The experience had changed their lives. They shared memories that only fellow tour members could really understand. They shared music—after 90 performances and who knows how many rehearsals, they knew each other’s voices inside and out. Who would want to give that up? “We have a tie,” Griffith says, “and it’s not just the past.” Laura Shapiro puts it another way. “All those things just got planted in your soul. And so you go back to that every five years and water it again.” Each reunion, the singers reclaim a little bit of their younger selves’ wide-eyed amazement, “but I think mostly you get to feel how that time fed you. And it did, in ways you could never define or articulate. In a million different ways.”

After Forbes died in 2006, Dan Hathaway ’67 and Carlotta Wilsen Woolpert, M.A.T. ’68, assistant conductors on the Asian Tour—both of whom went on to musical careers—stepped into his role, choosing and leading the songs for each reunion, keeping in mind the changing range and timbre of the singers’ aging voices. “We’re like Toscanini’s orchestra that kept playing after he died,” Griffith says. He notes how faithfully each reunion is attended, even after all these years. This past spring, 68 singers showed up. Fourteen from the original group have died; of the others who were missing, Griffith says, “I can give the exact reason why they can’t come. Everyone is accounted for.”

Across the decades, the chorus has gained a few new voices: a musical spouse or two, or Glee Club or Choral Society members who couldn’t make the Asian Tour. One of those adopted into the circle is Linda Perry, an opera singer whose husband, Lew Perry ’69, was the first person the group lost. He died in 1977, at 29 years old. An embolism. “He sang first tenor,” his wife says, “this beautiful, silver sound. It was that kind of voice—you never forgot it.” Lew had talked a lot about the Asian Tour—Linda knows all the stories by heart—and some years after his death, she received a letter inviting her to a reunion. She wrote back to say she was coming, and that she didn’t want to just sit and listen. A low alto, she could sing her husband’s part, replacing the voice the choir was missing. “Send me the music,” she said.

Fifty years in the making

The group had been planning this year’s reunion since the get-together they held in 2015 out in Estes Park, Colorado, where they’d trained in isolation before setting off on their big adventure in 1967. “We decided, gee, who knows, we might not make it to 50,” Bill Reardon ’68 says, “so we did a forty-eighth reunion.” But they did make it to 50, and on a Wednesday afternoon in late April, everybody arrived in Cambridge and checked into the Sheraton Commander Hotel.

The schedule for the following five days was packed—receptions and rehearsals and catered lunches and early breakfasts and more rehearsals, two a day, and a couple of hours here and there of free time. The highlight of it all, at least on paper, was the second of three slated performances, a Saturday night concert in Sanders Theatre, in black suits and dresses, singing with the Harvard Choruses and a full orchestra. “Everybody thinks we’re gone and put out to pasture,” Griffith says, “but here we are performing with the Glee Club and the Choral Society and the Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum. A bunch of old fuddy-duds.”

But a different concert, the one they sing every time, remains the deep heart of each reunion: a Saturday morning ceremony in Memorial Church to remember the people they’ve lost. Each time, there are eulogies for those who have died since the last reunion, and this year Laura Shapiro got up and spoke about Marilyn Wilt, who’d been with her 50 years ago for that stunning tea ceremony on a woody hillside in Japan.

After their memorial concert this past April, members of the fiftieth reunion gather on the steps outside.

Courtesy of Kathy Reardon '67

“You see us just being with ourselves,” Griffith says. “Sub specie mortis. Looking at the aspect of death. Everybody knows it. That is powerful.” In the sanctuary, three listeners sat in the first pew, perfectly still; otherwise the church was empty, except for ringing voices and the echoing organ. The choir sang Mendelssohn and Brahms and a Moses Hogan spiritual. For long minutes, the looping harmonies of Franz Biebl’s Ave Maria soared from the choir stalls, an almost impossibly gorgeous, haunted sound. Afterward, in jackets and raincoats, the singers—some as young as 67, none of them older than 72—gathered quietly on the steps of the church for a group photo. “Ready?” said the woman behind the camera. “OK, smile.”

And then a few hours later, they were in Sanders Theatre, that “beautiful little rosewood box,” Griffith calls it, for what felt like their biggest recital since maybe the Asian Tour itself. The day before, Harvard Choruses director Andrew Clark had dropped by a rehearsal in the small auditorium of First Church on Garden Street—the singers’ reunion headquarters—to walk through the music with them. They were singing A Child of Our Time, an oratorio by twentieth-century English composer and dedicated pacifist Michael Tippett. Written between 1939 and 1941, the piece was inspired by Kristallnacht. It’s a difficult, chilling chronicle of oppression and inhumanity, with some almost unsingably brutal lyrics (“Curse them! Kill them!…They infect the state”) and unmistakable resonances, Clark said, for today’s world (“Pogroms in the east, lynching in the west”). “The main theme,” he explained to the group, “is: how did we get here? What can we say about oppression? How do we process scapegoating? Where does culpability lie, and what is the way forward? What is the state of the world?”

Full of what Clark called “found objects”—a tango, bits of Jungian psychology, Bach Passions, Handel’s Messiah—Tippett’s oratorio winds itself around four African-American spirituals that intersperse the narrative and “become a sort of Lutheran chorale,” Clark said, “the moment when we reflect on the trauma that’s just taken place and what is about to follow.” But instead of using four-part Lutheran hymns, Tippett “pulled from a tradition that had experienced its own trauma and oppression and scapegoating”: African-American spirituals. The composer had heard a radio broadcast of them and later said that a trumpet had sounded in his soul. He wrote to the publisher of James Weldon Johnson’s 1922 collection The Books of American Negro Spirituals to ask for a copy. And he started writing A Child of Our Time.

Those spirituals were what the Asian Tour group would sing. Sitting in the audience, close to the stage, they formed a fourth chorus—a kind of Greek chorus, Griffith observed, and when they rose from their seats and began to sing, adding their voices to the voices on stage, the little rosewood box shook. “Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus.” It was hard not to cry. The sound was almost wild somehow, almost incandescent. An hour later, after the bass soloist had sung of “no final grieving, but an abiding hope,” and of moving waters that renew the earth, the Asian Tour group rose for the final time, to deliver the spiritual that closed the oratorio. “Deep river, my home is over Jordan,” they sang, slowly, then slower. “Lord, I want to cross over into campground.”

Then the voices and instruments vanished into silence, and for a full 12 seconds, people in the audience sat stunned and mute before they remembered to clap. As the applause finally rained down, Griffith welled up with tears. “Did you hear that?” he said a few moments later, as the lights came up and the audience began to disperse. His voice was almost a whisper. “Did you hear that?” Linda Perry reached up and gave him a hug. The Asian Tour singers would perform again the next morning at a campus church service with the University Choir, but this night was a punctuation mark. “Even if this were the last time we ever got to sing,” Griffith said, “I would still be happy.” He paused for a beat, thought about that again. Finally he added, “But we will sing again.”