All family snapshots look alike, except to the people in them—and except, perhaps, to Elsa Dorfman, BI ’73. But the thousands she’s taken over the years, all Polaroid portraits, really are exceptional. For one thing, they’re 24 inches tall and 20 wide, produced by a 200-pound camera that’s one of only six of its kind in the world. Then there’s their clarity, printed, according to Dorfman, with some of the most beautiful film ever manufactured and never, ever, to be made again—the demand is too low, and the chemical reagents too difficult to obtain.

Back in 1994, for a small show of her work at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), she conducted a playful census of her oeuvre. “Largest group photographed: 26 people, four generations. Age of youngest person: 14 days.…Age of oldest person: 94.…Number of people wearing T-shirts: 437.…Number of families who posed with a pet rabbit: 3.…Worst experience by far: family of 12; eight members each blinked once. Most frequent subject: Allen Ginsberg.…Best metonymic prop: steering wheel brought by suburban mom.”

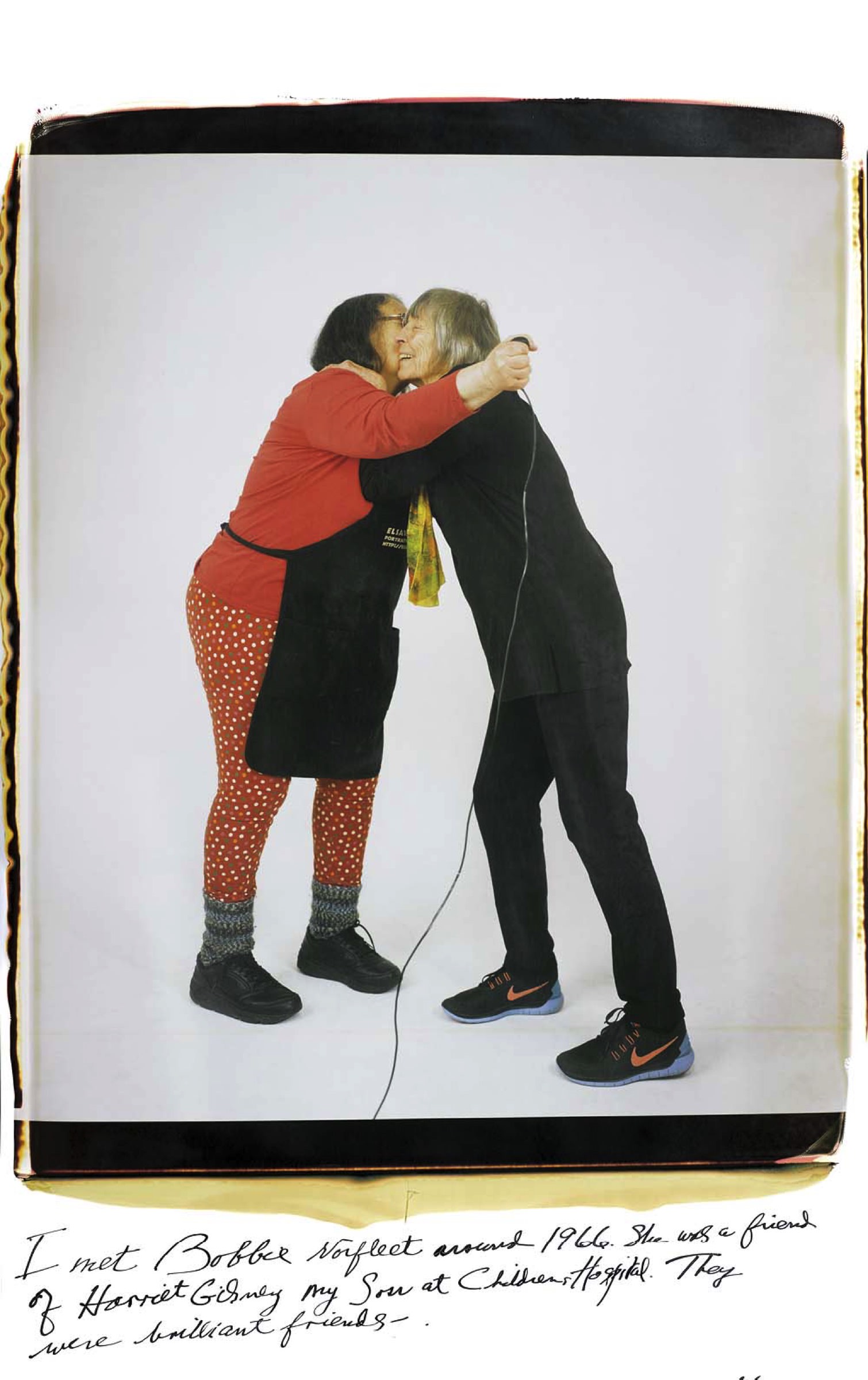

In her home studio in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the portraits in her possession are filed flat and organized by year. Family photos are basically ritual objects, meant to be pored over together, to be strip-mined for information: how Mom used to wear her hair; Dad’s hippie phase; that was the style back then. They furnish evidence, and provide an excuse to compare memories and come to some agreed-upon version of the story. On a dreary winter afternon, heater rattling, Dorfman goes through the images with the help of her longtime neighbor and self-described “wrangler,” retired sociology professor Margot Kempers, BI ’92, and supplies commentary for each one. Of herself posing with a client’s kickline of bridesmaids, all in different huge pastel hats: “Oh, that’s pretty weird, you’ve gotta admit.” Of three shirtless young men, wings tattooed across their pallid clavicles: “Oh! Oh! Their father was a banker!” And a more frequent refrain, now that she’s turned 80: “I hope they’re still alive. Life happens, that’s the horrible thing.”

She also savors little technical details, like the amber bar of light striping an image, or a fringe of blue ink at the top: “There’s no way of controlling it. It’s like a gift from the camera.” Once, she might have trimmed them away, to neaten everything up. Only in retrospect, now that Polaroid—the Apple of her day—is gone, and digital images can be infinitely duplicated, does that feel precious. Each Polaroid photo has always been a unique object, but somehow, now, that matters more.

Dorfman has lived south of Mass. Ave. and north of the Charles River for nearly 50 years, and in Cambridge for even longer. Born at Mount Auburn Hospital, she grew up in the Roxbury neighborhood of what was then, in her words, “Jewish Boston.” Her speech is salted with its wide-open R’s (yes, as in “Hahvahd Yahd”). Her website is designed to mimic the branches of the city’s subway. “For an American of my generation, I’m not well-traveled at all,” says Dorfman. “Europe on one end”—she studied abroad in Germany and France—“and California on the other.” And yet, says Gail Mazur, BI ’97, RI ’09, a poet who teaches at Boston University and Dorfman’s close friend since high school, “She was just, from my point of view, fearless. Not that she would jump off a four-story building or anything—but that any idea she had could be executed.”

Graduating from Tufts University, Dorfman moved to New York City and, at her job at Grove Press, befriended poets like Allen Ginsberg and Robert Creeley, her future collaborators. Yet she struggled to find a model of female artistic life. In Errol Morris’s new biographical documentary, The B-Side, she recalls, “There was no woman I met who wasn’t an alcoholic, promiscuous, or a druggie, but was also creative.”

So she returned to her hometown. She did what nice, practical girls did (go into teaching), and what they did not (refuse to live with their parents; instead she ran a poetry-reading circuit from a studio apartment 20 minutes away). She lasted a year at a classroom in Concord, where the fifth-graders called her not “Ellie” but “Miss Dorfman” and she shocked everyone by assigning Beat verse.

“It was so embarrassing not to be anything,” she has said of this period. One of the Concord parents, sensing her dislocation, suggested that she might find work at MIT’s Educational Development Corporation. At her summer position there, a colleague handed her a Hasselblad, her first camera. And so, at 28, Dorfman declared herself a photographer. She set up a darkroom right across from her bed, painting two of the walls black. “I was cavalier about darkroom chemicals,” she says.

She cobbled together a freelance living, mostly copy-editing and indexing books; she wrote poems. (A typed packet of these, with encouraging annotations from Ginsberg in pencil, now resides at Columbia’s manuscript library. Ask her about them, and Dorfman will let out a full-body, Muppety shudder: “Bleeeeegh!”)

Dorfman's Cambridge Studio

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Eventually, she started making money giving slide shows at colleges, selling images to textbook publishers, taking the odd commercial gig. A fellowship at Radcliffe College’s Bunting Institute paid her rent for two years. Showing her work there at an event in 1972, she recounted how when a real-estate agency hired her to take photos for their brochure, “They wanted pictures with the men’s desks neat. The men had to be wearing jackets and ties. You know how a man’s jacket sort of hikes up in the back, with a little pleat? None of that.” Most people weren’t interested in really good photographs, she explained, just ones with the right kind of information in them.

She was more interested in photographing people as they were. This inclination came from working with her first subjects: people dear to her. Dorfman started out taking photos of Mazur’s young children, and of the writers hanging out at the Grolier Poetry Book Shop. She got used to having her camera close at hand when she went out. Visitors would idly pick up the prints and look at them, and that encouraged her to take more. The images are straightforward and gentle, captured at a familiar but unintrusive distance: a friend draped over her couch, face down, for a nap; another cross-legged in her kitchen.

“When you live alone and you’re not married and you don’t have children, you have to invent ways of making your life responsive and gratifying. And I think one of the ways that I’ve done it is with my camera and with my work.”

While working on an article about marijuana legalization, Dorfman met a young criminal-defense lawyer fresh out of Harvard, Harvey Silverglate, LL.B. ’67. She remembers that when she knocked on the door of the law firm Crane, Inker & Oteri, for an interview, “The boss said, ‘Let the dame in!’ And there was this nice Jewish boy. Adorable! He was wearing what I thought was a wedding ring. But it turned out that was his father’s ring, and it was on the wrong hand, anyhow.” With sly humor, she would later versify an early date of theirs, consisting of supper at her place, for which he arrived two hours late, bearing a gift: “You came up the stairs/Carrying your salami like a banner/Baby, I thought/Is it ever long.” Silverglate became a frequent subject of her photographs. “I love taking pictures of Harvey, partly because it’s a switch on the usual combination—male photographer, female lover,” she wrote at the time. In 1968, she moved to a Harvard-owned duplex, on Flagg Street; he moved three houses up. “We broke up every year,” says Dorfman. They married in 1976.

In the new neighborhood, her ambit encircled Harvard’s undergraduate residence Mather House, where Dorfman got the position of “tutor” by walking into the office of its senior administrator and offering her services. She helped run the darkroom and taught noncredit photography seminars, eating dinner in the dining hall. She also became a fixture of Harvard Square, wrapped in a fur coat, selling photographs for a couple of bucks each out of a borrowed shopping cart.

The work from these years culminated in the 1974 publication of Elsa’s Housebook: A Woman’s Photojournal. Drawing on a tradition of women’s domestic diaries, her book reads like a personal album, each portrait hand-labeled with a name and date, and accompanied by chatty entries. The entries document an artist’s everyday inputs and outputs: the people who come and go, her enthusiasms, the way she scrapes by. But it’s also an implicitly feminist project, presenting the life Dorfman invented for herself as a young single woman. The book conveys the warp and weft of her social fabric, her existence enmeshed with others but also, and oddly, untethered. Presenting the work-in-progress at the Bunting Institute in 1974, Dorfman told her audience, “When you live alone and you’re not married and you don’t have children, you have to invent ways of making your life responsive and gratifying. And I think one of the ways that I’ve done it is with my camera and with my work. And I’ve matched my style as a person and my needs as a person living alone with this instrument, the camera.”

In the book, Dorfman writes, “The women’s movement has been an enormous help in making me comfortable. It’s made being unmarried less freakish; it’s challenged the notion that only life with children is complete.” Yet she wished she could unequivocally say that she didn’t want a family. “I wish I were tougher.”

Dorfman found her way into photography on the cusp of its coming of age as a fine-arts medium. In the 1970s, museums began to collect photographs, and private galleries to exhibit them; art schools started up formal training programs. A half-generation behind her, a group of young artists known collectively as the Boston School—Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia among them—documented the city’s subcultures and experimented with color, their portraits swooning and gritty, flirting with the lurid.

Boston was a hub for photography thanks to Polaroid. Originally founded as Land-Wheelwright Laboratories by two-time Harvard dropout Edwin Land ’30, S.D. ’57, and his physics instructor, they started out making polarizing sheets for use in objects from sunglasses and automobile headlights to gunsights and periscopes (see “The Polaroid Moment,” March-April, page 76). But photography equipment became Polaroid’s signature product, and artists were key to the tech company’s research and development process. At first, photographers like Ansel Adams were hired “primarily for their technical know-how, and their photos, when kept, were technical evidence,” writes art historian Peter Buse: “it was thought that they would make special demands on the film.” But by the late 1960s, with the founding of the Artists Support Program, the company had established a patronage system that put industry in the service of aesthetics. Polaroid invited photographers to Cambridge to use its studio space and technicians, and traded free film for publicity, feedback, and prints.

Land was a master showman of his inventions. The headliner of the 1976 shareholders’ meeting was to be a large-format 8-by-10-inch film for professional photographers. Three days before the event, Land decided that he wanted something even bigger. Using parts they had lying around, the staff of the company’s Miscellaneous Research unit engineered the 20 x 24 virtually overnight. Polaroid decided to build only a handful and disperse them strategically, and one ended up at the art school associated with the MFA. (Another massive Polaroid invention from that year also resided there: a whale of a camera—room-sized, and nicknamed “Moby C”—which could make life-sized replicas of artworks.)

“Working the darkroom, you have to be a man with a wife, or a woman without a family,” she says. “…And it’s domestic in a way. It’s washing, it’s stirring, it’s cooking, it’s like being a chef, and it’s thankless. It’s fun, but fun is the least of it.”

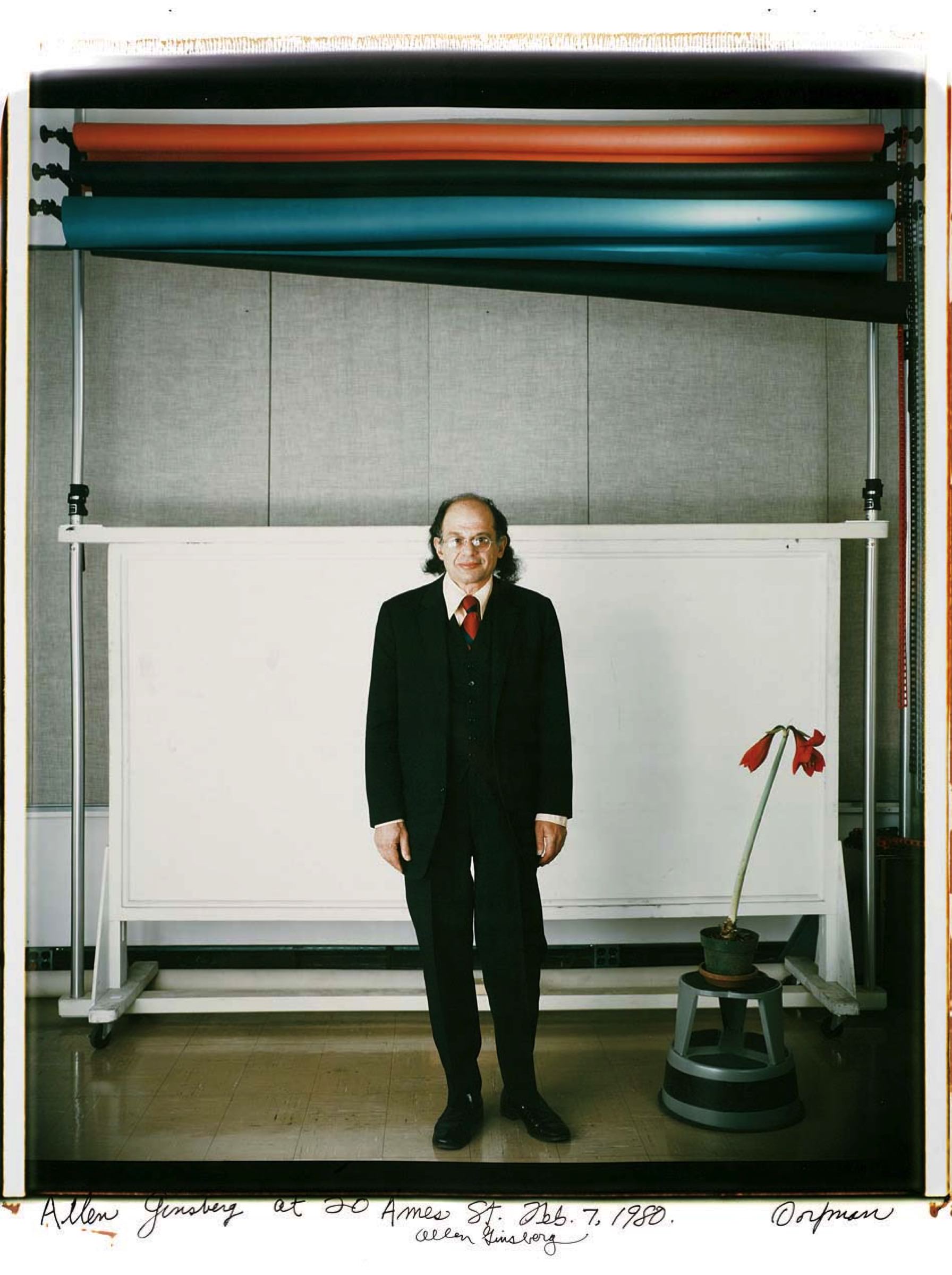

Contraptions had often charmed Dorfman. At the store of her friend Ilene Lang, M.B.A. ’73, she’d fallen in love with the instant poster machine, making 60 the first day she met it; she had similar zeal for the iTech machine at Harvard’s Carpenter Center, which could make large prints. (Just last year, she put out a new edition of the Housebook, using a robot that turned the original’s pages and held them flat to scan, and the “Paige M. Gutenberg” at Harvard Book Store, which prints perfect-bound books on demand.) In February 1980, she got her chance with the 20 x 24. Ginsberg and Orlovsky were in town for a reading, and she struck a deal with Polaroid: a subsidized portrait session in exchange for the two best prints.

The men wore suits to the studio, and snagged a closed red amaryllis, a gift from Silverglate, on their way out of her home. They posed with their books and musical instruments; they took all their clothes off. Only the first 10 exposures were free, but Dorfman, accustomed to small-format cameras and cheap film, clicked away. One of the most striking images from this session is of Orlovsky delicately picking a fleck of lint off Ginsberg’s suit. In the moment, she says, “I was so mad at myself, that I hit the shutter and I wasted 50 dollars! Because that was what a sheet of paper was, and I was so broke,” says Dorfman. Now, “Everybody looks at it, and says, Ohh.” Under the studio lights, the flower bloomed.

By this time, Dorfman and Silverglate were raising a young son, Isaac, having eloped before his birth, and naming Ginsberg and feminist writer Andrea Dworkin his godparents after. The demands of a young child and her husband’s career made photography more difficult. “Working the darkroom, you have to be a man with a wife, or a woman without a family,” she says. “It’s just a lot of work. And it’s domestic in a way. It’s washing, it’s stirring, it’s cooking, it’s like being a chef, and it’s thankless. It’s fun, but fun is the least of it. And then it’s time to pick him up at nursery school, and blah blah blah.” With Polaroid, the image was done as soon as she peeled it apart. The 20 x 24 offered her a way forward: she’d rent the camera for one day a month and take paying clients. She could make art amid her life, and a living from her art.

It’s become a critical commonplace to endow Polaroid’s instant photography with an almost anthropomorphic degree of warmth and intimacy. The 20 x 24 had an additional gift: it produced prints with an unusually high resolution. A number of influential photographers have used the camera: David Levinthal for his tableaux with miniature figurines, Ellen Carey for kaleidoscopic abstractions. Chuck Close once declared that one of its prints “contains an infinite amount of information.” But none have worked so exclusively with the camera as Dorfman. She says she was never one of Polaroid’s favored “pets,” but by 1987, when one of the 20 x 24s was returning stateside from Japan, she was on good enough terms with the company that she contrived to lease it indefinitely, for use in her private studio in a Cambridge office building. It’s been in her possession ever since.

Photograph by Elsa Dorfman

Photograph by Elsa Dorfman

Photograph by Elsa Dorfman

Photograph by Elsa Dorfman

Photograph by Elsa Dorfman

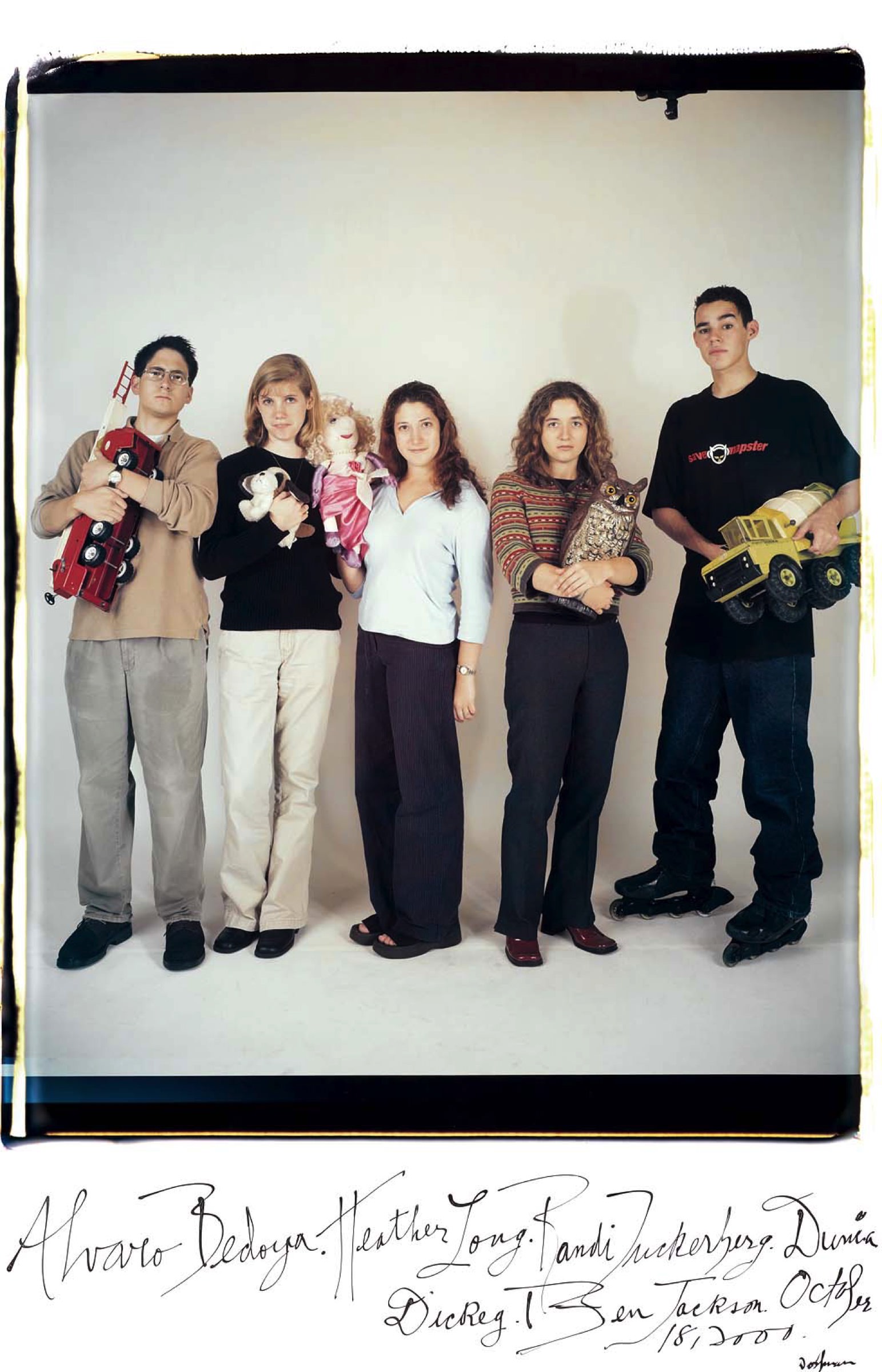

Land himself credited his three-year-old daughter Jennifer with the idea for instant photography: on vacation in Santa Fe, she’d asked why she couldn’t immediately see the pictures he’d taken. When the SX-70 was invented, the impatience and wonderment of children were key to its marketing: Life put Land on its cover in October 1970, surrounded by tow-headed tots reaching for his new toy. So naturally the bulk of Dorfman’s clients were families. She thrilled to see whole dynasties, with new generations and extended wings, checking in every few years; she had a soft spot for working with mothers and daughters. She worked well with children, but was initially leery of babies, who moved too quickly, and were too young to recognize their names when called. (Dogs had the opposite problem; they ran toward the speaker when named.) But other subjects also faced her lens: artist friends, Harvard professors, a biker gang, a whole series of women in their favorite Marimekko dresses. She invited Mather students to come by for sessions, hanging their portraits in the House.

Taking clients for the 20 x 24 was the first time Dorfman consistently photographed strangers. But that camera, with its wooden body, steampunk absurdity, and almost creaturely eye, helped—its presence was so unavoidable, and so alive, that it absolved people of their self-consciousness. So did the fact that she stood next to and not behind it, usually in stocking feet and an apron, as if her subjects had just dropped by for supper. Dorfman involved them in a theatrical ritual: assembling themselves against the white backdrop, holding still, checking the print, then getting back to place for the next shot.

For all that the 20 x 24 was the exemplary Polaroid camera, it also cut against key features of instant photography. The average camera was a great party prop, a means for strangers to approach each other, bonding with a flash. The general consumer liked that prints were cheap, and lots could be made quickly and collected; they were appealingly, immediately tactile, and could be passed around, hand to hand. The 20 x 24 was obviously laborious, its prints expensive (now $10,000 for a session), and meant for display (Dorfman custom-framed hers under Plexiglass). The images took hours to dry.

It was also slow. Operating the 20 x 24 is highly physical, usually requiring some assistance, though Dorfman managed solo until age and kidney disease interfered a few years ago. She’d wheel the camera into position and step on a stool to see through the focusing screen, fiddling with the bellows to focus the lens and closing the door on the back. A cable release triggered the shutter. The camera exposed the negative with the open lens, and sandwiched it with the positive between a set of rollers, bursting a chemical pod. Dorfman, kneeling—she’s compared it to both midwifery and prayer—would pull out the exposure and cut it off the roll. Then she would wait for 70 seconds, a built-in timer counting the seconds in red.

The whole thing was rife with suspense. Subjects would crowd around as she peeled away the negative—presto!—to reveal the image. The excess chemical gunk would be scraped off with a knife resting on the foot of the camera, or a stiff piece of scrap positive paper, staining the linoleum with rusty spatter. Amid all these logistics, she managed to create an air of spontaneity, telling her clients, to a one, “Let’s have fun, you look lovely,” and meaning it every time. She loved what people looked like. “This will be easy,” she’d often say. “Look! It’s easy.” The final step was for her to caption and sign the bottom in India ink.

The resulting images sometimes feel like a play on those monumental Renaissance portraits in which lacquered significance is built up stroke by stroke, the subjects’ hands resting coyly on a symbolic ledger or cupping a jar of ointment. Posing for Dorfman, actress Faye Dunaway sat with playwright William Alfred (then Lowell professor of the humanities), arm wrapped around a copy of his play Hogan’s Goat. Other subjects surrounded themselves with camping gear, cradled baguettes in their arms, and dressed up in tuxedos while wielding power tools.

“There is something both straightforward and so fresh, both modest and proud, you know?” says Anne Havinga, photography curator at MFA (which holds nine of Dorfman’s Polaroids). “There’s something so wonderfully casual about them—and consistently so.”

“There’s humor in this work, which you don’t often see in portraiture,” comments Makeda Best, curator of photography at the Harvard Art Museums (which holds 29). Dorfman rarely got to choose her subjects; clients called her. And yet, asks Best: “Are they commissions, or collaborations?”

She photographed her own family innumerable times. On the whole, these Polaroids feel far less formal—some taken at New Year’s and proms, but many for no reason at all. One of her favorites is of Silverglate in a light-reflecting yellow safety vest (she made a diptych, snapping him front and back). Another night, she had her husband and son pad down Mass. Ave. to her basement studio for a group portrait in their red-flannel pajamas. The expressions on their faces are sometimes amused, sometimes playing along, other times seeming just barely to humor her, ready to get the hell aboveground. These photos feel less like events than like occasions she conjured from everyday life, moments pilfered from the timestream.

Along the way, Dorfman also made self-portraits. At first, she did this to understand what her subjects felt under her lens. Now, she likes to attribute it to her lifelong myopia. “Well, if I take off my glasses and I look in the mirror, I can’t see myself,” she explains. “Most people have a really good idea of what they look like.” Dorfman thinks the Polaroids of herself are less angsty than the black and whites from her youth—perhaps because the prints were so much more expensive, required so much more setting up, that by the time the shutter clicked she’d been reminded of all the things that she enjoyed about her life. One common motif, across the years and aesthetic phases, is the long shutter-release cable extending from her hand to the camera—like an umbilical cord, or an astronaut’s tether.

Dorfman can be evasive about her work. She’s happy to discuss all the surrounding circumstances—but any transcendent artistic truths are kept close to the chest. In an essay, she once wrote that she never sought to capture anyone’s soul—but if any was revealed, it was hers. Asked now, after her decades in the business, what she thinks she might reveal, she says, “Oh, I don’t know. What if I knew? It’d be creepy. Don’t you think?”

She does say that a central part of her practice is to make her subjects comfortable. “I sort of go to the most vulnerable person in the group. I can do it very fast. Really, within four minutes.” What’s the tip-off? Oh: “Something. If I knew, I would be on Brattle Street taking patients.” She goes on, “So I really concentrate on making that person comfortable. And sometimes I’m way off, but I try.” So is it that she makes herself vulnerable to that person? “No. No...it’s my wanting to take care of people, I suppose. Or—,” she stops herself. “I don’t know! I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know. And I think actually if I knew, I would ruin it.”

This mental stoppage is surprising, coming from someone whose eye is so frank, and whose manner is so unselfconsciously open. On a typical visit, Dorfman opened the door caroling, “The spirit of youth is here!” She greeted strangers with a broad smile, a question mark at the corner, expecting nothing, open to anything. Over a split tuna fish sandwich, from the café down the street, she’d lose her breath laughing, a high, giddy cackle.

A respect for people—not just for their privacy, but for what they wish to show—runs deep. Compared to, say, Diane Arbus, she had limits, and missed her chance to take certain pictures as a result. That ruthless forwardness was Arbus’s genius, Dorfman reflected in the Housebook: “It separates her from all the rest of us.” But her own unwillingness to take what was not readily offered was what forged her connection with others. She took people as they wished to appear, the face they’d prepared to meet the faces that they meet. “For me,” she has said, “the key word is ‘apparently.’”

For years, Gail Mazur counted herself as someone dear to Dorfman whom the artist couldn’t photograph. When they were young, Dorfman took the author photo for Mazur’s first book. “She didn’t love it any more than I did,” Mazur reports. “We felt that somehow we couldn’t pull it off. And it had to be my fault.” She didn’t like the camera; she was too concerned with how she looked. Then, in 2008, “I realized one day that I had to learn how to have Ellie take my picture.” Mazur had caught a snippet of a TED talk by Amy Cuddy (then a faculty member at Harvard Business School) about “power poses” in body language. That was it: she’d stare down the 20 x 24, standing like Wonder Woman. Mazur loves that photo, she says, “But I also think it’s funny that I assumed a virtue that I didn’t have. It must have made Ellie happy too, because I wasn’t acting afraid of the camera.” In it, only one hand remains on Mazur’s hip—the other is at her side. She’s standing in a three-quarters turn toward the camera, like she’s fallen out of the pose, caught in mid-laugh.

Though some over the years have dismissed Dorfman’s portraits as too sunny or only skin-deep, the images collectively form a worldview, and together advance an ethic. Each photo is a compact between her and her subject, a sprightly conspiracy. A person’s appearance is not a mask to rip off, a wrapper to tear away, a shell to pierce—no need for some drastic excavation. These convivial social surfaces rustle on their own: with earnestness, with anxiety, with cheer (false or real), with solemnity. Her work is a gentle reminder of the vitality of the exterior, those outmost layers that brush up against each other every day. This eddying sociability is what everyone swims in, that carries us, with more or less effort on our part, through all our days. Dorfman’s work says: this is the water that surrounds us, and it also sustains.

Polaroid weathered the new millennium badly. Between 2001 and 2009, the company declared bankruptcy twice, and was sold three times. In 2006, it ceased camera production. In 2008, it announced that it would stop producing instant film, demolishing its manufacturing equipment.

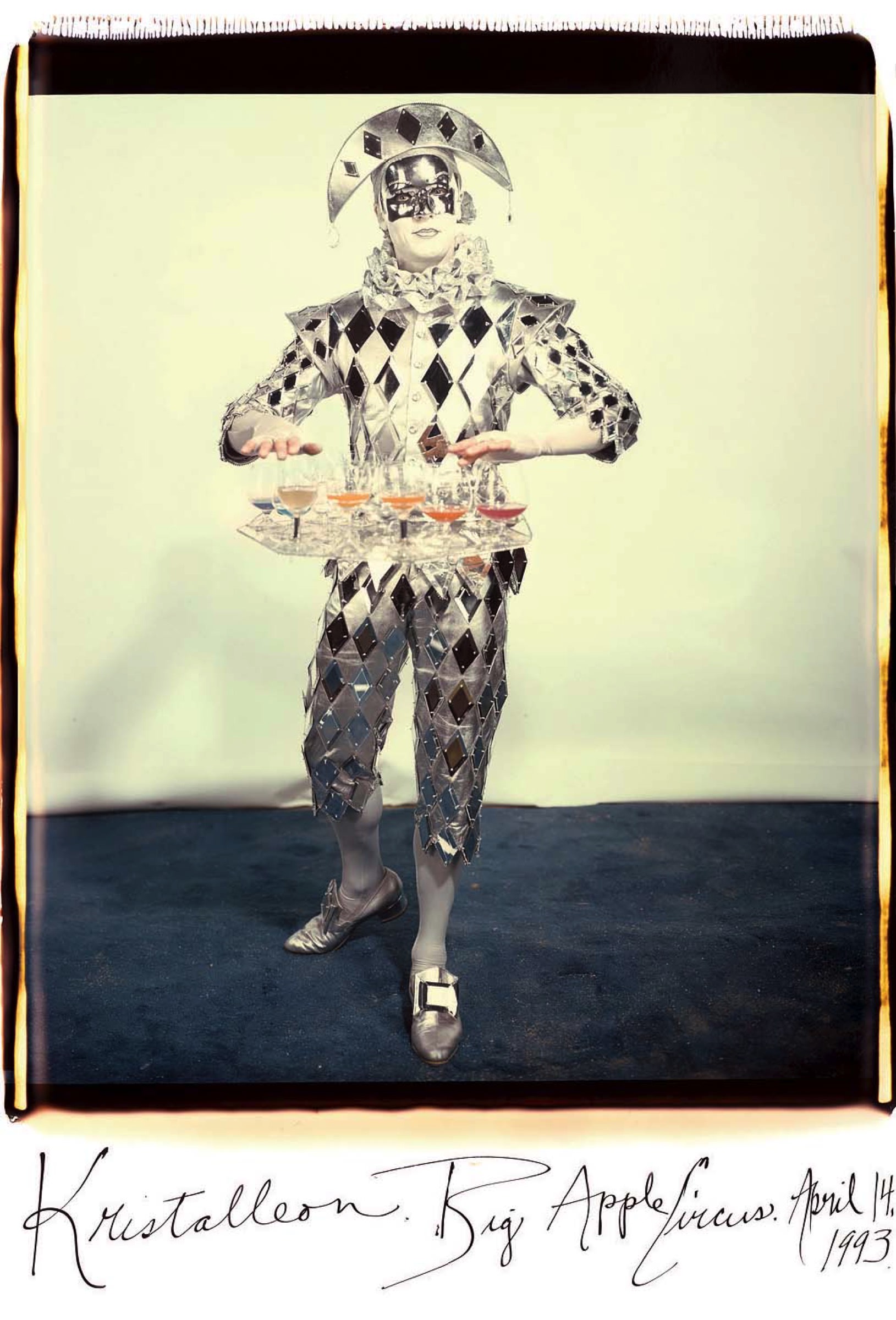

Dorfman called up venture capitalist Daniel Stern ’83, M.B.A. ’88. While studying at the Business School, he’d been one of her first tenants in what was then her family’s new residence in Cambridge. Over the years, she had photographed his parents, wife, and kids; when she wanted to shoot the performers of the Big Apple Circus, he convinced them to let her take her equipment into the ring. With Stern’s funding, a group of former Polaroid employees and 20 x 24 devotees bought six years’ worth of film and paper, a pod-filling machine, and a reactor, and figured out how to mix up new batches. Stern even commissioned two new cameras, which now operate in San Francisco and New York City.

When the greatly exaggerated news of the 20 x 24’s death reached Ronald Jou ’01, he got alarmed. He remembered biking down to Dorfman’s studio as a student at Mather House, and thinking very little of it. “My classmates and I just signed up,” he said in a recent phone interview. “We exchanged a few words and shook hands, but we didn’t actually end up spending that much time with her.” It had seemed so easy at the time—lots of students were doing it. Their portrait hung in the House with the rest, and when the friends graduated, buying it seemed so out of reach that they joked about returning for a reunion to “borrow” it. Jou learned more about the 20 x 24 and Edwin Land while in medical school in San Francisco, and recalled that his freshman research position had been in a lab in the Land building. He became more intent on having the photo. When he graduated from residency, his wife surprised him with it—all with Dorfman’s aid and abetment. For months she fielded Jou’s frantic emails, pretending to have misplaced it. It hangs in the family’s Palo Alto loft.

“I look at it all the time,” he says quietly, and when he does, “I see three kids who—thought they knew a lot. We were a year short of graduation. Bobo [Kwabena Blankson ’01] and I were both applying to medical school, and we thought we pretty much knew everything. And then, when I look back, I know that obviously we knew nothing. At all. That photo in 2000 was taken 10 years and one day before my oldest son was born…your whole life changes.” Knowing that the film stock was dwindling, Jou and Blankson rushed to get their families together in Cambridge for a reunion photo in May 2016. In it, one of their young daughters is holding a powder-blue plastic instant camera, jauntily, in her right hand.

One of the ironies of Polaroid’s last years was that the demand for its instant film didn’t fall to zero. As recounted by journalist Christopher Bonanos in his book Instant, the supply of film that was projected to last a decade ran out in five; sales were brisk. Its cultural cachet was strong enough that when the photo-sharing service Instagram launched in 2010, its logo riffed on the Polaroid camera, and allowed users to add filters and frames that aped the real-life thing. Today, companies like the Impossible Project manufacture instant film. Vintage re-sellers do good business on Ebay; retailers like Urban Outfitters sell instant cameras brand new.

In 1970, Land dreamed of a time when taking out a camera would be as reflexive as taking a wallet out of one’s pocket, “a camera that you would use as often as your pencil or your eyeglasses.” We live in the world that Polaroid created: one of mass amateur photography, constant documentation, instant images, and the habit of sharing. On social media, photos are used not to commemorate but communicate—in fact, with popular services like Snapchat, these postcards from the present disappear within seconds. So interest in the analog endures, as does investment in physical objects. If the prints’ chemistry is unstable, and prone to fading, that, too, has an appeal: the Polaroid haze feels like a gentle alternative to the ruthless clarity of digital image or the scrutiny and high publicity of digital life.

It’s happened that the close of Dorfman’s career has brought a flurry of media attention, from well beyond Boston—in particular, a New York Times profile in January 2016 that she thinks spurred her old friend Errol Morris to make The B- Side, the film about her he’d been threatening for years. (“He’s sort of an eccentric torturer,” she says, fondly.) For one scene, the crew came to record an errand at her home: movers coming to take a pair of 40-by-80-inch portraits for scanning. Morris made them repeat the action over and over again—maneuvering around corners and handing them gingerly down three floors—for hours before he was satisfied.

When her friend Ilene Lang made a short black-and-white movie about her in the 1970s, Dorfman found it odd to be so passive, and to have no control over what would be recorded. But for the Morris project, she committed. “I made up my mind that if I was going to do this, I was going to do it right.” Though the film often shows Dorfman holding her photos up and in front of her face, her eyes just peering over the top edge, she resolved to answer all of their questions, and not “to create some sort of character.” Dorfman, Kempers, and the producers met weekly, looking at old photographs, documents, her high-school yearbook—hunting, she says, for triggers for her memory.

The B-Side may seem unusually sweet-tempered to viewers who know the documentarian’s more confrontational, investigative films. But other affinities make Dorfman a natural subject for Morris, and Morris an ideal portraitist for her: his work, too, has been profoundly shaped by the grace of a marvelous machine, in his case the Interrotron, which uses a system of mirrors so that interviewees could speak while staring dead-on into the lens.

For the movie’s premiere at the Telluride Film Festival last September, Dorfman flew out to Colorado, and the camera followed on a truck. Though at this point she ordinarily takes only a few photographs a day, during that weekend, though sick with the flu, she took 47—a dizzying array of celebrities, including Janelle Monáe, Mahershala Ali, Casey Affleck, and Clint Eastwood, as well as some of the most exciting pets she’d ever encountered: two golden eagles from Mongolia. (“You have no idea how big they were. They were as big as two filing cabinets!”)

Photograph by Elsa Dorfman

When all the circumstances align—when her health is good, and the photo paper and chemicals and technical help are available, and the camera behaves, and there’s an eager client—Dorfman still shoots the occasional portrait. “I can’t bring myself to clean my studio and close the door and turn the key,” she says. “Especially if it’s a lovely person.”

Mostly, though, she’s turned her attention from producing work to preserving it. She and Kempers are arranging to digitize and store the photographs, and organizing her papers. Just the other day, Dorfman says, they stumbled on the original manuscript of the Housebook, wedged in a cabinet.

Sitting on a stool in her framing studio, portraits laid out on various surfaces, she gazes around her. “I must say, I feel really good, looking at these. I should come out here when I’m feeling, ughhhh,” she says. “I know that they’re marvelous. You know, when I’m up there, singing with the angels…”

A strong intellectual tradition has made photography out to be a singularly melancholy art, its every exposure shadowed by loss. Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida was sparked by his mother’s passing; Susan Sontag declared, “All photographs are memento mori.” In The B-Side, Dorfman herself wonders if photographs arrive at their ultimate meaning only after the subject has died. Yet her images themselves insist otherwise: Silverglate in his fluorescent vest; a clown blowing a bubble; a plump cat spilling out of its owner’s arms; the toddler clutching a juicebox. These photos may be talismans, a futile attempt to ward off change. And yet they glow, as if with the possibility of an afterlife.

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,