In 2013, a manifesto entitled The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study began making the rounds among the growing pool of nervous graduate students, harried adjuncts, un-tenured professors, and postdocs whirling through the nation’s faculty lounges. The Undercommons was published by the small anarchist press Autonomedia and made freely available for download; in practice, however, it circulated by word of mouth, copies of the PDF forwarded like samizdat literature for those in the know. On the surface, the text is an analysis of alienated academic labor at the contemporary American university. But it’s also more radical than that: it is a manual for free thinking, a defiant call to dissent within educational institutions that betray their liberal credos, filling their coffers even as they prepare students, armed with liberal arts degrees and “critical thinking” skills, to helm a social and economic order in which, “to work…is to be asked, more and more, to do without thinking, to feel without emotion, to move without friction, to adapt without question, to translate without pause, to desire without purpose, to connect without interruption.”

For those with little or no knowledge of black studies, the text’s deployment of terms like “fugitivity” and “undercommons” may seem baffling. To those in the circle, however, this lexicon of continental philosophy, remixed with a poetic and prophetic fire resembling Amiri Baraka’s, bears the signature of one of the most brilliant practitioners of black studies working today: the scholar and poet Fred Moten ’84.

Black studies, or African American studies, emerged out of the revolutionary fervor of the late 1960s, as students and faculty members demanded that universities recognize the need for departments engaged in scholarship on race, slavery, and the diasporic history and culture of peoples of African descent. Since its institutionalization, these departments have grown many branches of inquiry that maintain a rich interdisciplinary dialogue. One is a school of thought known as jazz studies, which investigates the intersections of music, literary and aesthetic theory, and politics. Moten is arguably its leading theoretician, translating jazz studies into a vocabulary of insurgent thought that seeks to preserve black studies as a space for radical politics and dissent. In his work he has consistently argued that any theory of politics, ethics, or aesthetics must begin by reckoning with the creative expressions of the oppressed. Having absorbed the wave of “high theory”—of deconstruction and post-structuralism—he, more than anyone else, has refashioned it as a tool for thinking “from below.”

Moten is best known for his book In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (2003). “The history of blackness is testament to the fact that objects can and do resist,” is the book’s arresting opening sentence, announcing his major aim: to rethink the way bodies are shaped by aesthetic experience. In particular, he explores how the improvisation that recurs in black art—whether in the music of Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday, the poetry of Amiri Baraka and Nathaniel Mackey, or the conceptual art of Adrian Piper—confounds the distinctions between objects and subjects, individual bodies and collectively experienced expressions of resistance, desire, or agony. Since 2000, Moten has also published eight chapbooks of poetry, and one, The Feel Trio, was a finalist for the National Book Award in 2014. He is that rare literary figure who commands wide and deep respect in and out of the academy, and who blurs the line between poetics as a scholarly pursuit, and poetry as an act of rebellious creation, an inherently subversive activity.

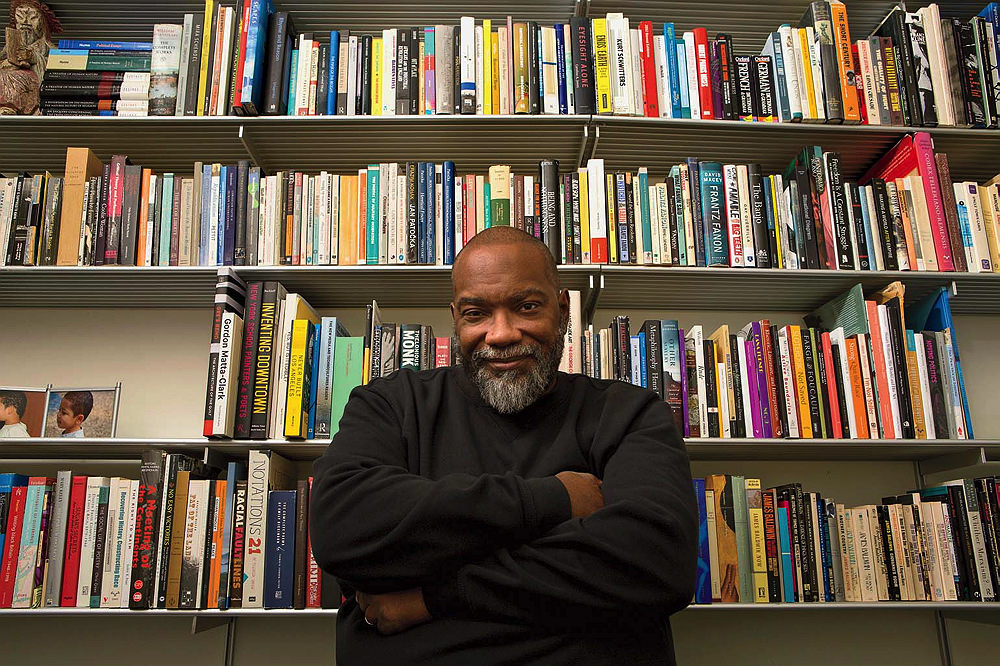

This past fall, Moten took up a new position in the department of performance studies at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, arriving from Los Angeles and a teaching appointment at the University of California at Riverside. In early September, his office was still a bare room with a single high window looking out over Broadway. He hadn’t had a chance to unpack his library, but already a small stack of books on jazz theory, performance, and quantum mechanics rested in a pile near his desk. It soon became clear, however, that he is the kind of thinker who keeps all his favorite books in his head, anyway. His Paul Laurence Dunbar is always at his fingertips, and he weaves passages from Karl Marx, Immanuel Kant, or Hortense Spillers into his conversation with equal facility.

In someone else this learnedness could come off as intimidating, but in Moten it’s just the opposite. Something about his composure, his relaxed attentiveness, the way he shakes his head with knowing laughter as he pauses over the direction he’s about to take with a question, instantly erases any stuffiness: one can imagine the exact same conversation taking place on the sidelines of a cookout. And then there’s his voice: warm, low, and propelled by a mellow cadence that breaks complex clauses into neat segments, their hushed, conspiratorial air approaching aphorism. At one point, Moten asked about my dissertation, which I confessed, sheepishly, was kind of a mess. His eyes lit up. He leaned back with a wide grin, his hands spreading out in front of him. “You know what a mess is?” He said. “In Arkansas, a mess is a unit of measure. Like of vegetables. Where my people come from folks might say: ‘You want a bushel?’ And you’ll say, ‘Nah, I want a mess.’ You know, like that great James Brown line: ‘Nobody can tell me how to use my mess.’ It’s a good thing to have. A mess is enough for a meal.”

When he’s speaking before an audience, no matter the size, he never raises his voice; a hush comes over the room and remains in ambient tension, like a low flame. On the occasion of John Ashbery’s ninetieth birthday last July (just months before his passing), Moten collaborated in a celebratory recording of Ashbery’s long poem, Flow Chart. Ashbery was always a great reader of his own work, but it was thrilling to hear the sly affection with which Moten took the verse uptown, bending its notes with his Lenox Lounge delivery. The same qualities come out when he reads from his own poetry, always brimful of quotations from the songbook of black America. His poem, “I got something that makes me want to shout,” for example, consists of riffs that build off quotations from a celebrated funk record, each quote set off just enough and in just such a way —“I got something that tells me what it’s all about”—that when he lands on the last line of the poem—“I got soul, and I’m super bad”—he’s fully sublimated a James Brown groove. The line between poetry and song quivers, the “high” lyric gets down with the low, and the Godfather of Soul’s declamation of Soul Power boomerangs back to us as poetry, which is what it always was.

A Cosmic Rent Party

To understand how all the pieces that “make” Fred Moten come together, one has to step back and see where he’s coming from. The autobiographical reference is a constant presence in his poetry, in which the names of beloved friends, colleagues, musicians, kinfolk, neighbors, literary figures, all intermingle and rub up against each other like revelers at a cosmic rent party. “I grew up in a bass community in las vegas,” opens one poem from The Feel Trio: “everything was on the bottom and everything was / everything and everybody’s. we played silos. our propulsion / was flowers.”

Moten was born in Las Vegas in 1962. His parents were part of the Great Migration of blacks out of the Deep South who moved north and westward to big cities like St. Louis and Los Angeles. By the 1940s and 1950s they were also being drawn to Las Vegas, and the opportunities offered by the booming casinos and military bases established during World War II. “A lot of people don’t realize it, but Vegas was one of the last great union towns,” Moten says. Jobs within the gaming industry were protected by the Culinary Union, and with a union check, even casino porters and maids could save up to buy a house—“at least on the West Side,” the city’s largely segregated black community where he was raised.

Moten’s father, originally from Louisiana, found work at the Las Vegas Convention Center and then eventually for Pan American, a large subcontractor for the Nevada Test Site where the military was still trying out its new atomic weapons. His mother worked as a school teacher. (She appears often in his poetry as B. Jenkins, also the title of one of his finest collections.) Her path to that job was a steep climb. Her family was from Kingsland, Arkansas, and had committed themselves against all odds to obtaining education. Her own mother had managed to finish high school, says Moten, who remembers his grandmother as a woman with thwarted ambitions and a great love of literature. She’d wake him up in the mornings by reciting poems by Dunbar and Keats she’d learned in high school. “And she was the one who was really determined for my mother to go to college,” he says. “She cleaned people’s houses until the day she retired, and in the summer and spring she would pick cotton.” Kingsland is the birthplace of Johnny Cash, and Moten’s family picked cotton on the property of Cash’s cousin Dave, a big landowner, to get the money together to send his mother to college.

Jenkins attended the segregated University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, which housed her in the dormitory basement; she eventually transferred to, and graduated from, the Arkansas Agricultural Mechanical and Normal College, at Pine Bluff.* She was keen on doing more than just learning; she wanted to pursue knowledge for its own sake, and for how it might serve to explain the world around her. “My mother totally believed in the value of education,” Moten says, “but she was scholarly in a certain way. She was invested in learning in a way that was disconnected from the material benefits it was supposed to get her, and I must have picked up on that.” She was especially interested in sociology, and he grew up hearing her talk about figures like Horace Mann Bond, Hortense Powdermaker, Gunnar Myrdal, and John Dollard, towering figures of the liberal school of American social science who were engaged in solving what was then commonly referred to as “the Negro Problem.”

Degree in hand, she went to Chicago to teach in the public schools, but “someone basically told her she was too dark to get a teaching job in Chicago.” She hoped to have better luck in Vegas, but the schools were segregated there, too, and no one would hire her. “They used to call Nevada the Mississippi of the West,” Moten recalls. Jenkins took up domestic work, and it was only by chance that she found herself cleaning the house of a woman who was on the local school board, who helped her get a job at Madison Elementary School on the West Side, where she met Moten’s father.

The West Side was a tightly knit community. Moten likens it to the village in the Toni Morrison essay “City Limits, Village Values,” where Morrison contrasts white fiction writers’ “Gopher prairie despair” with the affection black writers typically express for the intimate, communal life built around “village values”— even if that black village, like Harlem, say, is part of a larger city. “It seemed like everybody was from one of these tiny little towns in Arkansas. My mom’s best friends—their grandparents were friends.” Nevada was a small enough state, he says, that the West Side could swing tight elections, and much of Las Vegas politics in the early 1960s was concerned with national politicans’ positions on civil-rights legislation. “So a few precincts in Las Vegas might make the difference between the election of a senator, Paul Laxalt, who probably wouldn’t vote for the Civil Rights Act, or the election of a Howard Cannon, who would, and my mom was deeply involved in all that.” Through her, politics and music became intertwined in everyday life.

Though the flashpoint of national politics at the time was school desegregation, locally it was also about desegregating the Vegas Strip. “You know, you see all that Rat Pack shit in the movies,” Moten says, “but the truth of it was that Sammy Davis Jr., Duke Ellington, Count Basie—they could perform on the strip, but they damn sure couldn’t stay there. So when they came to town they would come to the West Side and stay in rooming houses, and there was this amazing nightlife on Jackson Street where you could hear everybody.” Everyone, from headliners to pit-band musicians, came to stay on the West Side. Moten’s mother knew a number of musicians, dancers, and singers; when jazz singer Sarah Vaughan came to town they would gather at a friend's house to cook greens, listen to music, and gossip. “For me that was like school,” he says. His childhood summers, meanwhile, seemed to revolve around listening to Vin Scully and Jerry Doggett doing the Dodgers broadcast: “My family were all rabid Jackie Robinson-era Dodgers fans.”

Moten also has strong memories of listening to KVOV, “The Kool Voice of Vegas.” “It was one of those sundown stations, you know, that shuts down for the night, and they had a disc jockey named Gino B. Soon as the sun started getting low, he would put on a bass line and start rapping to himself…bim bam, slapped-y sam, and remember everybody life is love and love is life...that kind of thing, and everybody in town would tune in just to hear what he was going to say, and I loved that.” He also vividly recalls encountering certain LPs in the 1970s, like Bob Marley’s Rastaman Vibration and Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions—“those double-gated record albums that had the lyrics printed on the inside, so you could sit and read while the music played overhead.” Aside from his grandmother’s love of it, he says, his first experience of poetry was music.

From Harvard to the Nevada Test Site

For a kid from a midsize Western city, the shock of going East to college at Harvard might have been overwhelming. Moten felt he was ready for the challenge. He was lucky to have folks looking out for him, he insists—like David L. Evans, an admissions officer who was “like a hero to us”: “Any black student from the late ’60s onward, you can believe he had to fight like Mayweather, Ali, Frazier, and Joe Louis to get us in.” Moten’s first surprise at Harvard was encountering a certain kind of black elite. “My growing up was a lot more like Good Times than it was like the Huxtables, and now I was in a school with a lot of Huxtables.” The even bigger shock was campus politics. “When I went to Harvard in 1980 I thought I was being trained for the Revolution. The Black Panther party in Vegas—they met in my mom’s basement. So I was ready to go, and I had foolishly assumed everyone there would be thinking like me.”

Moten’s first surprise at Harvard was encountering a certain kind of black elite. “My growing up was a lot more like Good Times than it was like the Huxtables, and now I was in a school with a lot of Huxtables.” The even bigger shock was campus politics.

Moten originally planned to concentrate in economics, taking Social Analysis 10 and a class on development economics that he vaguely imagined might lead to agricultural development work in Africa. Freshman football helped him through his first semester by providing a loose structure without too strenuous a commitment—but by the second, things were getting messy. He was very influenced by Professor Martin L. Kilson, a scholar of black politics whom Moten describes as “a great man and a close mentor,” and to whom The Undercommons is dedicated. He was also increasingly involved in the activities of politically minded friends—tutoring prisoners and working with civil-rights activists in Roxbury. After a while he got too busy to go to class. He was also awakening to a world of ideas and intellectual debate. “We were staying up all night, we were reading everything, just none of it was for class.” The group discovered Noam Chomsky, and got deeply involved in exchanges between E.O. Wilson and Stephen Jay Gould about sociobiology and scientific racism—“and we felt like we were in the debate, like we were part of it, you know, we were very earnest and strident in that way. But eventually it caught up to me that I had flunked three classes and I had to go home for a year.”

This turned out to be a transformative experience that can only be described as Pynchonesque. When he got home, he ended up taking a job as a janitor at the Nevada Test Site, busing in through the desert each day. “The Test Site was the last resort for a lot of people. If you really messed up, you might still be able to get work there,” he says now. He worked pretty much alone, but for an alcoholic man from Brooklyn who’d somehow drifted west, and would regale Moten with stories about growing up in Red Hook. “I’ll never forget, he always called me ‘Cap’: ‘I wanna succeed again, Cap!’”

Fred Moten

Photograph by Robert Adam Mayer

“It was eight hours of job but two hours of work,” Moten recounts, “so mostly what I did was read.” He got into T.S. Eliot by way of seeing Apocalypse Now and reading Conrad. “‘The Hollow Men’ and ‘The Wasteland,’ those were very important poems for me. There was this scholarly apparatus to them, a critical and philosophical sensibility that Eliot had, that you could trace in the composition through the notes.” He’d pore over a newly released facsimile edition to “The Wasteland” that included Eliot’s drafts. “By the time I came back, I was an English major.”

Back in Cambridge, it was an exciting and tumultuous time to be jumping into literary studies. He took an expository writing class with Deborah Carlin, who introduced him to Alice Walker and Zora Neale Hurston and encouraged him to write; he took Helen Vendler’s “Modern American Poetry” class, where he first encountered Wallace Stevens, Frank O’Hara, and Allen Ginsberg, “And I realized that I could read it, I could get it.” Reflecting, he adds, “I was glad that I had taken the class with Vendler and the class meant a lot to me, but I also already knew my taste differed from hers.”

At the same time, Moten was cultivating a relationship to campus literary life, joining The Harvard Advocate, where he met its poetry editor, Stefano Harney ’85—forming a close and enduring friendship that has also evolved into an ongoing intellectual collaboration (Harney is co-author of The Undercommons). Together, they took a class taught by David Perkins on the modernist long poem, reading William Carlos Williams’s Paterson, Robert Duncan’s “Passages,” and Ed Dorn’s The Gunslinger. “I was into that stuff, and Steve was, too, so we could cultivate our resistance to Vendler together.” Parties were off campus at William Corbett’s house in Boston’s South End, where fellow poets like Michael Palmer, Robert Creeley, or Seamus Heaney might stop in for dinner or drinks. Moten absorbed the possibilities of the scene but his poetic sensibility is that of the instinctive outsider, attracted to all those who dwell at the fringes and intend to remain there.

A decisive turning point came when literary critic Barbara Johnson, arrived from Yale to teach a course called “Deconstruction,” and he first read Jacques Derrida, Paul de Man, and Ferdinand Saussure. At the time, in a class on James Joyce, he was also reading Ulysses. “It had a rhythm I was totally familiar with, but that I didn’t associate with high art. I believed, I just sensed that it was radical; it felt instinctively to me like this was against the status quo, that the reason they wrote this way was that it was like a secret, it wasn’t for the bosses.” He felt the same way about Derrida: “This is for the people who want to tear shit up. And we were ready for it.”

The Poet-Philosopher of Weird

Moten went on to pursue graduate studies in English at Berkeley. Even his earliest journal publications are intensely idiosyncratic. It’s as if he were convinced he had to invent his own tools in order to take up the subjects that interested him—design his own philosophy, his own theory. “I’m not a philosopher,” he says. “I feel like I’m a critic, in the sense that Marx intends in Private Property and Communism when he gives these sketchy outlines of what communism might look like: ‘We wake up in the morning, and we go out in the garden, till the ground, and in the afternoon we engage in criticism.’”

In his criticism, Moten is especially attuned to a zone that Brent Edwards (a close friend and interlocuter) has called the “fringe of contact between music and language.” He’ll draw the reader’s attention to the “surplus lyricism of the muted, mutating horns of Tricky Sam Nanton or Cootie Williams” in Duke Ellington’s band, for example. Or, commenting on Invisible Man’s observation that few really listen to Louis Armstrong’s jazz, he’ll cut to an abrupt and unsettling assertion: “Ellison knows that you can’t really listen to this music. He knows…that really listening, when it goes bone-deep into the sudden ark of bones, is something other than itself. It doesn’t alternate with but is seeing; it’s the sense that it excludes; it’s the ensemble of the senses. Few really read this novel.”

In one of In the Break’s most transfixing passages, Moten reassembles a new set of meanings, or understandings, of the photograph of Emmett Till’s open casket. Why should that image, out of all others, have so much power—some even arguing, as he points out, that it triggered the mobilization of the civil-rights movement? Why has it remained so charged and fraught, so haunting? “What effect,” Moten asks, “did the photograph of his body have on death?” His answer: captured within the image is the sexual panic occasioned by the sound of Till’s whistling, “ ‘the crippled speech’ of Till’s ‘Bye, baby,’ ” forever bound up in the moaning and mourning of a mother over her dead child. Looking at the photograph, Moten writes, “cannot be sustained as unalloyed looking but must be accompanied by listening and this, even though what is listened to—echo of a whistle or a phrase, moaning, mourning, desperate testimony and flight—is also unbearable.” Millions have viewed the photographs of Till’s open casket. His images have been infamously and controversially reproduced, looked away from, gawked at. Moten does with extraordinary care what most have never done for Till (or for so many other sons and mothers), out of ignorance, or fear, or shame—which is, of course, to listen.

Moten is impatient with detractors who accuse him of difficulty and lack of clarity. Many writers once thought to be impenetrable are now considered canonical, he points out. “The critics I loved and who were influential to me were all weird: Empson, Burke, Benjamin, Adorno—they all had a sound, and it wasn’t like a PMLA, academic-journal sound.” The other critics who influenced him, he continues, were poets: Charles Olson, Amiri Baraka, Nathaniel Mackey, and especially Susan Howe—who, he says, has a different understanding of how the sentence works. “Miles [Davis] said: You gotta have a sound. I knew I wanted to sound like something. That was more important to me than anything.” One could argue that Moten’s sound resonates with the “golden era” of hip-hop of the late eighties and early nineties, when it was still audibly a wild collage of jazz, R&B, late disco and funk: “Styles upon styles upon styles is what I have,” the late Phife Dawg raps on A Tribe Called Quest’s celebrated 1991 album The Low End Theory.

One difficulty for outside readers encountering Moten’s work is that he tends to engage more with the avant-garde than with pop. It’s easy to see why the art world has embraced him: his taste gravitates toward the free-jazz end of the spectrum so strongly it’s as if he were on a mission, striving to experience all of creation at once—to play (as the title of a favorite Cecil Taylor album puts it) All the Notes. This spring, Moten is teaching a graduate course based on the works of choreographer Ralph Lemon and artist Glenn Ligon. In recent years he has collaborated with the artist Wu Tsang on installation and video art pieces, where they do things like practice the (slightly nostalgic) art of leaving voicemail messages for each other every day for two weeks without ever connecting, just riffing off snippets from each other’s notes. In another video short directed by Tsang, Moten—wearing a caftan and looking Sun Ra-ish—is filmed in “drag-frame” slow motion dancing to an a cappella rendition of the jazz standard “Girl Talk.”

“I grew up around people who were weird. No one’s blackness was compromised by their weirdness, and by the same token, nobody’s weirdness was compromised by their blackness.”

By way of explanation, Moten recalls his old neighborhood. “I grew up around people who were weird. No one’s blackness was compromised by their weirdness, and by the same token,” he adds, “nobody’s weirdness was compromised by their blackness.” The current buzz (and sometimes backlash) over the cultural ascendancy of so-called black nerds, or “blerds,” allegedly incarnated by celebrities like Donald Glover, Neil deGrasse Tyson, or Issa Rae, leaves him somewhat annoyed. “In my mind I have this image of Sonny Boy Williamson wearing one of those harlequin suits he liked to wear. These dudes were strange, and I always felt that’s just essential to black culture. George Clinton is weird. Anybody that we care about, that we still pay attention to, they were weird.”

Weirdness for Moten can refer to cultural practices, but it also describes the willful idiosyncracy of his own work, which draws freely from tributaries of all kinds. In Black and Blur, the first book of his new three-volume collection, consent not to be a single being (published by Duke University Press), one finds essays on the Congolese painter Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu and C.L.R. James, François Girard’s Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould, a comparison between Trinidadian calypso and Charles Mingus records composed in response to the Little Rock Nine, David Hammon’s art installation Concerto in Black and Blue, Wittgenstein and the science fiction of Samuel Delany, a deconstruction of Theodor Adorno’s writings on music and a reconstruction of Saidiya Hartman’s arguments on violence. Sometimes the collision can happen within a single sentence: “Emily Dickinson and Harriet Jacobs, in their upper rooms, are beautiful,” he writes. “They renovate sequestration.”

Taken together, Moten’s writings feel like a Charlie Parker solo, or a Basquiat painting, in their gleeful yet deadly serious attempt to capture the profusion of ideas in flight. For him this fugitive quality is the point. We are not supposed to be satisfied with clear understanding, but instead motivated to continue improvising and imagining a utopian destination where a black cosmopolitanism—one created from below, rather than imposed from above—brings folks together.

For Moten, this flight of ideas begins in the flight of bodies: in the experience of slavery and the Middle Passage, which plays a crucial role in his thinking. “Who is more cosmopolitan than Equiano?” he asks rhetorically, citing the Igbo sailor and merchant who purchased his own freedom, joined the abolitionist movement in England, and published his famous autobiography in 1789. “People think cosmopolitanism is about having a business-class seat. The hold of the ship, among other things, produces a kind of cosmopolitanism, and it’s not just about contact with Europeans and transatlantic travel. When you put Fulani and Igbo together and they have to learn how to speak to each other, that’s also a language lab. The historical production of blackness is cosmopolitanism.”

“Trump is nothing new. This is what empire on the decline looks like. When each emperor is worse than the last.”

What can one learn from the expression of people who refuse to be commodities, but also once were commodities? What does history look like, or the present, or the future, from the point of view of those who refuse the norms produced by systems of violence: who consent not to be a single being? These key concerns course through the entirety of Moten’s dazzling new trilogy, which assembles all his theoretical writings since In the Break. At a time of surging reactionary politics, ill feeling, and bad community, few thinkers seem so unburdened and unbeholden, so confident in their reading of the historical moment. Indeed, when faced with the inevitable question of the state of U.S. politics, Moten remains unfazed. “The thing I can’t stand is the Trump exceptionalism. Remember when Goldwater was embarrassing. And Reagan. And Bush. Trump is nothing new. This is what empire on the decline looks like. When each emperor is worse than the last.”

* * *

A thesis that has often been attractive to black intellectuals (held dear, for example, by both W.E.B. Du Bois and Ralph Ellison) was that the United States without black people is too terrifying to contemplate; that all the evidence, on balance, suggests that blackness has actually been the single most humanizing—one could even say, slyly, the only “civilizing”—force in America. Moten takes strong exception. “The work of black culture was never to civilize America—it’s about the ongoing production of the alternative. At this point it’s about the preservation of the earth. To the extent that black culture has a historic mission, and I believe that it does—its mission is to uncivilize, to de-civilize, this country. Yes, this brutal structure was built on our backs; but if that was the case, it was so that when we stood up it would crumble.”

Despite these freighted words, Moten isn’t the brooding type. He’s pleased to be back in New York City, where he’ll be able to walk, instead of drive, his kids to school. He’s hopeful about new opportunities for travel, and excited to engage with local artists and poets. His wife, cultural studies scholar Laura Harris, is working on a study of the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica, who is currently being “re-discovered” by American artists and critics. “I circulate babylon and translate for the new times,” opens another poem in The Feel Trio, referring to a timely, or maybe timeless, place where “secret runway ads brush and cruise each other and / the project runaway.”

Moten is not in the business of promoting optimism for the future, but he does not feel imprisoned by the past or bogged down in the present. Instead he is busy prodding about the little edges of everyday life as it is expressed by everyday people, the folkways of the undercommons. As his writings circulate within and beyond the classroom, so too does his version of theorizing from below, always seeking out sites where a greater humanity might unexpectedly break through.