When Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen were assistant professors at the University of Rochester, they got to talking over lunch about politics. What made the United States more conservative than other Western democracies? Within America, what made the South more conservative than other regions, especially on race-related issues? And what explained differences within the South? Take the 2008 presidential election. Barack Obama won next to zero support from white residents of Greenwood, Mississippi and its surrounding county, who are among the most conservative voters in the country; he won 57 percent support from white residents of the Asheville, North Carolina area, long considered a progressive enclave.

The researchers argue that chattel slavery caused political divides that still exist in the South. White people living in counties where slaveholding was more prevalent tend to be more conservative and more hostile toward black people. Greenwood, set on the alluvial plain of the Mississippi Delta, became a major cotton producer in the nineteenth century; by 1860, enslaved people made up 68 percent of its population. Asheville, meanwhile, started as a trading outpost within the Blue Ridge and Smoky Mountains, and in 1860 only 15 percent of its population was enslaved. “It’s not simply that more conservative people live in these areas—these are more conservative areas because of their past,” they write in their new book, Deep Roots: How Slavery Still Shapes Southern Politics.

“This is a break from what research in political science and public opinion might tell us,” acknowledges the introduction. Blackwell, now an assistant professor of government at Harvard, says that usually in political science, “Objects of study are paired closely in time.” Studies will link local opinions on affirmative action to an area’s current demographic makeup, for example, or support for the Whig Party in 1860 to cotton exports from that decade. In contrast, their study investigates processes that unfolded over more than a century and a half.

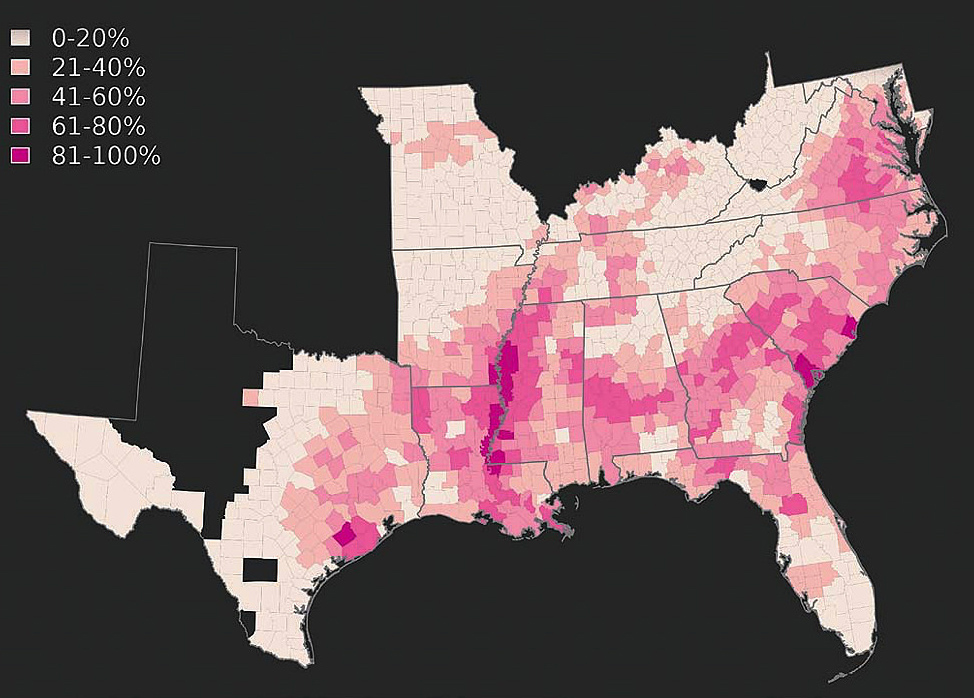

Slavery in the United States, 1860

The density of slavery is shown within modern county boundaries.

Courtesy of Matthew Blackwell and Maya Sen

Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen took historical data about slaveholders and enslaved people from the 1860 census and mapped that onto modern-day counties, where they had survey data that recorded party affiliation, stances on race-related issues, and measures of racial resentment. They also looked into data from the Reconstruction era: after the Civil War, counties that once had high slave populations became areas with high rates of lynching—and in these counties, today, white survey respondents express “cooler attitudes” toward blacks. The trio’s study also considered other reasons why formerly slave-holding areas are more conservative. For example, perhaps slavery affected where in the South different groups ended up living, which in turn influenced political attitudes—or perhaps an area’s political attitudes actually predated, and indeed drove, slavery. But neither fit the data.

The researchers posit that areas with economies reliant on slavery passed “Black Codes” to control black people’s movements and their political and economic activities, and to secure cheap labor. Social norms governing how blacks and whites interacted in public further reinforced the racial status quo, and were passed down by parents to their children. Local governments, schools, and churches encouraged these sentiments as well. Long after the original economic incentives faded, racial attitudes persisted.

First published in a paper in 2016, their conclusion drew mixed reactions. “We’ve had two general classes of responses,” reports Sen, now an associate professor at the Kennedy School. “‘Well, it’s obvious that history should and does have an impact on present-day attitudes. So what you do is astoundingly obvious.’ That’s one category of response. And the other category is exactly the opposite, where people say, ‘It’s outrageous that you think that something that collapsed 150 years ago still predicts how I think, or still predicts how I vote.’”

With their book, the researchers hope to convince people that their current beliefs are directly tied to the past. They also advance a theory they think could apply to contexts beyond the United States: when an important institution collapses, a society makes choices about how to proceed, and the political attitudes that form during that critical moment are passed down through the generations. “Once a community has moved along a path,” the authors conclude, “it becomes firmly rooted and difficult to reverse or change.” Though the original incentives no longer apply, the disparities persist, even as, in this case, Americans across the board are more racially tolerant than in the past.

This divide may last even longer in the absence of behavioral interventions like the truth and reconciliation commissions set up in post-apartheid South Africa and post-genocide Rwanda. The United States has had major legal interventions, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which promised equal access to the vote and to public resources, but “in terms of trying to change people’s hearts and minds,” Blackwell says, “the government never really got involved in that, either at the national or the state level.”

Deep Roots joins a growing body of what’s known in the social sciences as “persistence literature.” For example, a 2011 study found that anti-Semitism in Germany has persisted at the local level for centuries: cities that witnessed pogroms after the Black Death in the fourteenth century also saw more violence against Jews in the 1920s and more votes for the Nazi party. Abbe professor of economics Nathan Nunn, at Harvard, and professor of politics Leonard Wantchekon, at Princeton, have shown that even today within Africa, individuals whose ancestors lived in communities that were heavily raided during the transatlantic and Indian Ocean slave trade are less trusting.

In political science, a field where a lot of effort goes into measuring the impact of outreach strategies—sending a mailer to a potential voter, making a phone call, sending a volunteer to knock on doors—studies like Deep Roots take a longer view. “It’s trying to understand really long-term forces that dictate who opens the door,” says Sen—and how that person might react.