Six days inching through heavy sand, a truck falling into an aardvark hole, blazing days and frozen nights: the Marshalls weren’t on a typical family vacation when they set out into the Kalahari Desert, in present-day Namibia, in June 1951. Laurence Marshall was freshly retired from Raytheon; his wife, Lorna, taught English at Mount Holyoke. Also along were their teenagers, Elizabeth and John, plus some scholars, interpreters, guides, mechanics, cooks, and other helpers. Backed by Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, they were searching for the semi-nomadic indigenous people they called “Bushmen” (and later, more precisely, the Ju/’hoansi and /Gwi).

In six more trips over the ensuing decade, the Marshalls documented the daily lives of the hunter-gatherers in 40,000 photographs. Some will be displayed, alongside past and present images of the people of the Nyae Nyae, in “Kalahari Perspectives: Anthropology, Photography, and the Marshall Family,” at the Peabody Museum from September 29 through March 31, 2019.

N!ai in 1955. Image gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall ©President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Photograph probably by Daniel Blitz/PM# 2001.29.633.

The Marshalls had no formal training in anthropology or photography, but their fieldwork methods were unusually holistic for the time, says curator of visual anthropology Ilisa Barbash. They lived with Kalahari families for up to 13 months at a stretch. John learned to hunt giraffes and pigs with the other young men; one woman named her daughter after Lorna. The Marshalls’ strikingly naturalistic images (as above, of a toddler, ≠Toma, showing Elizabeth Marshall a caterpillar) always identified their subjects by name.

Westerners have depicted “Bushmen” to suit their own ends: whether as scientific specimens to be classified, to speed up colonization, or as elusive exotics, to burnish their own renown as adventurers. In her book, Where the Roads All End, Barbash argues that the Marshalls projected an image of gentle people who deserved special consideration from the state. But the sheer size of their collection has given subsequent scholars latitude for their own interpretations.

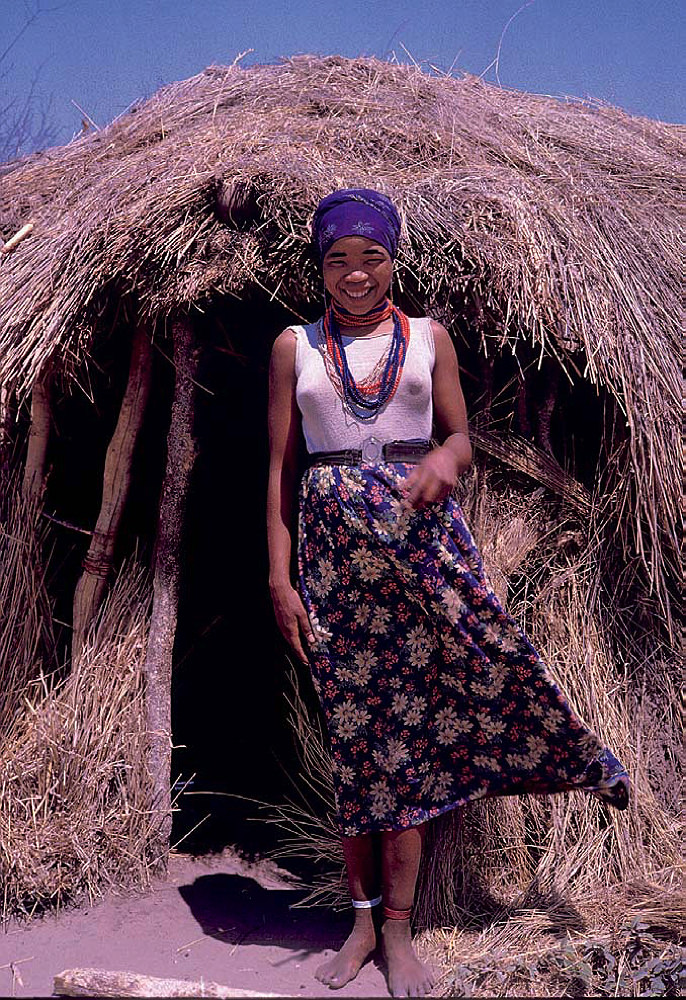

N!ai in 1961. Image gift of Laurence K. Marshall and Lorna J. Marshall ©President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Photograph probably by Daniel Blitz/PM# 2001.29.656

Some of the Marshall images became so popular that outdated romantic notions about the region persisted long after its inhabitants’ lives had changed. Pushed into fixed settlements by the government during the 1960s, they built huts from mud and straw and adopted Western clothing, as shown above in the two portraits of N!ai, a young Ju/’hoansi girl, from 1955 and 1961.

John Marshall later regretted that these photographs elided how much, and how rapidly, the groups’ lives were changing—a record he tried to correct later in life in his advocacy and groundbreaking documentaries. When Barbash first began work with the archive, he told her, “Make sure you don’t leave these people in the past.”