Harvard’s course offerings used to take the form of thick paper catalogs, filled with numbers and descriptions of the thousands of classes available in the curriculum each semester. In 1990, the University began offering its current online catalog listing, my.harvard, alongside these physical books, which it finally ceased printing after the 2008-2009 academic year. Researchers with metaLAB (at) Harvard believe that it is time to update and transform the course catalog again, from my.harvard to a system that displays the curriculum as a network of connections, a continuous landscape that does not segregate courses by departmental divisions.

To explain why it was important to create this new system, Jeffrey Schnapp, founder and faculty director of metaLAB, gives the example of a student who is interested in studying Shakespeare. On my.harvard, which is currently students’ primary method of searching the curriculum, a student could look through the English department’s offerings and find one of the several Shakespeare courses offered there. But how is he or she to discover Shakespeare’s presence outside of the English department, in fields like anthropology, sociology, government—courses that consider Hamlet in the context of the history of psychiatry, for example, or King Lear as it relates to sixteenth-century English political upheaval?

It is important to view the curriculum not as “a series of discrete objects,” Schnapp says, but as “a living, pulsing thing—a kind of organism that reflects the values of a university, the areas of knowledge that it ascribes value to.” To capture the curriculum in this way, metaLAB researchers have created Curricle, an online platform that allows students to explore the curriculum through data visualization and mapping techniques.

Work on Curricle began in 2015, at the behest of Diana Sorensen, then-dean of the arts and humanities. The concern was that my.harvard encouraged students to “[isolate] one course from the other and [treat] courses as a list or inventory,” Schnapp says. So, students were settling into comfortable niches before fully exploring all of the courses available to them, and they were picking “more and more vocational paths” through the curriculum.

Curricle aims to give students the ability to follow intellectual threads and find courses outside of the familiar. “Our attempt was to focus on exploration—not shopping, but exploration,” Schnapp says, criticizing the “course shopping” metaphor that students commonly use to describe the sampling of courses before official enrollment. “When you’re shopping, you usually already know what you want. Exploring is a little different. With exploring, you might find certain things interesting…,” he suggests, and “you’re drifting around, looking laterally, checking out the landscape.”

Curricle is just one project among many under way at metaLAB, says Schnapp, who has been studying how data science can enhance understanding across scholarly disciplines for decades: he was the director of the Stanford Humanities Lab from its founding in 1999 until 2009, and he has headed metaLAB since founding it in early 2011, leading a variety of projects focused broadly on the reorganization of information, using digital tools to enhance the utility of, for example, libraries and museums.

Curricle’s most immediate, low-level impact is allowing students to visualize and understand the curriculum in new ways. But the sort of “institutional innovation” that Schnapp envisions would be an even deeper change, which he hopes Curricle’s values will inspire: an understanding that the curriculum is not just a means to an end, a list that should be efficiently organized so that students can pluck from it a handful of courses to take each term. Instead, the curriculum itself is a reflection of its institution. “I think this platform is really about thinking differently about what an institution is, what a university is, what a college is. The word universitas—I’m a medievalist by training—means universe,” he says. “It is the whole universe of knowledge that universities claim to capture. But, of course, that universe changes over time, with technological progress, the social questions dominant in a given era, with tastes, with shifts in cultural values.

“We're really interested in the way in which a curriculum tells a story. It tells a story about the values of an institution, what it cares about, what it thinks of the disciplines that make up the world of learning, when certain kinds of transformations happen, fields that rise, fields that fall,” Schnapp continues. “So, in a sense, it's probably the most profound expression of what a university is at any moment of its evolution.”

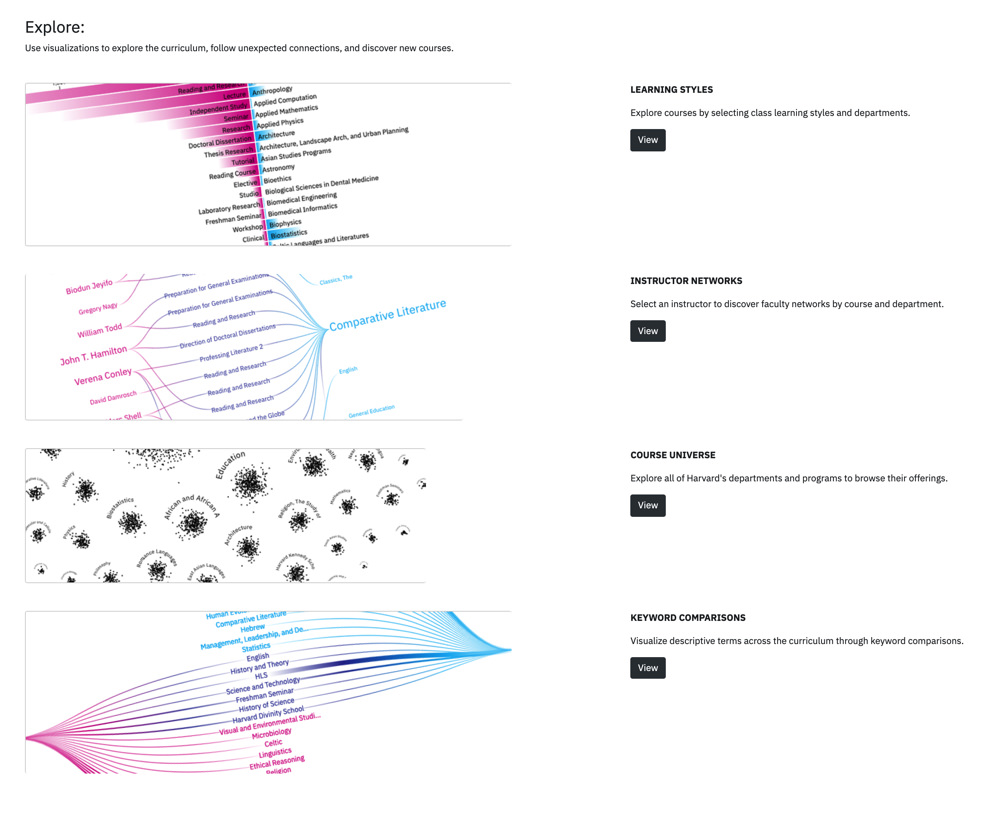

Curricle was tested for the first time this past spring semester, with about a quarter of the student body making use of it at some point. The platform offered four different ways of searching for and exploring courses:

- “course universe,” which displays a zoomed-out version of every course offered at Harvard in a given semester, represented as dots within different departments;

- “instructor networks,” which maps connections between instructors based on factors like co-teaching relationships and citations on syllabi;

- “learning styles,” which allows students to sort courses based on classroom approaches like seminars, lectures, and workshops; and

- “keyword comparisons,” which displays the appearance of terms that users can input across the curriculum.

Kim Albrecht, who developed these data-visualization techniques, says he started the process of designing and creating them by “looking into the data and experimenting with different possibilities,” based on his own interests and those of students.

Harvard offers about 1,500 classes each semester. “So,” Albrecht continues, “the question was: How can we create alternative interfaces, how can we use visualizations to show different paths through those courses?”

This fall, an expanded beta test of Curricle will include new features such as the ability to see transcript data in the platform and the ability to transfer courses directly to my.harvard, where students must officially register for them.

Researchers at metaLAB hope Curricle’s impact extends beyond more stimulating course selections for students. For example, visual representations of the curriculum can be useful for University affiliates ranging from alumni, who might be interested in what courses were offered during their student years, to administrators, who can use Curricle to visualize the curriculum not only across departments and schools but also across years and decades.

And, in the long term, the future that researchers envision for Curricle is larger than even Harvard itself. “Our hope is that come 2020, maybe some other universities will get in the mix,” Schnapp says. He gives the example of public universities, where students must often navigate curricula even bigger than Harvard’s. Another feature that researchers may eventually incorporate is the ability to visualize connections between the registrar’s course offerings and the HarvardX curriculum, which offers free online classes, so that students can see all of their options as they make decisions—a framework which, Schnapp says, might be useful for other colleges that are part of consortia through which students can register for courses at multiple schools.

“If we perceive a need or problem at Harvard, the likelihood is that [the same] need or problem is shared with a wide variety of other institutions,” Schnapp says. “Our hope is that we can start to catalyze a larger shift within universities and colleges that starts to bring us into the digital age in some ways that are informed by the values that are integral to the design of Curricle.”

Learn more about other efforts to make use of the information in course contents and syllabi here.