Equestrian life and sports have long shaped Boston’s North Shore. In the late nineteenth century, that primarily agricultural region, with industrial hot spots along the coast and Merrimack River, evolved into “the premiere summer colony of affluent Bostonians, many of whom were avid equestrians,” according to a new exhibit at the Wenham Museum: “They rode, hunted, drove carriages, played polo, golf and tennis, swam, and sailed their yachts and steam launches.”

Within a 25-mile radius of the museum, says its director of external affairs, Peter G. Gwinn, sporting grounds and facilities for fox hunting, polo, dressage, and three-day eventing emerged over time, drawing riders and fans from across the world. The exhibit strives to “bring riders and non-riders together to learn about, and share, the importance of these sports and traditions,” he adds. “We also hope to highlight the land, and the importance—to everyone—of open landscapes and conservation, which all began here because of the love of horses.”

Antique prints and tack-room gear

Photograph courtesy of Peter G. Gwinn/Wenham Museum

A continual driver of these traditions is the Myopia Hunt Club, in abutting South Hamilton, with its foxhunts, polo grounds, and golf course (designed in 1894 by Herbert Corey Leeds, A.B. 1877). It was established by a group largely composed of Harvard graduates, and, apart from two wartime breaks, polo players have competed on Myopia’s Gibney Field on summer Sundays since 1887.

Those matches, held this year from June 2 to September 29, are still open to the public. The $15 tickets are sold on site the day of a game; tailgating parties before and during the match are allowed. In addition, the Harvard Polo Club and its men’s and women’s teams—which feature in the museum exhibit, along with current head coach Crocker Snow Jr. ’61, a Myopia member and former championship-team polo player—are based at the Harvard Polo and Equestrian Center. It’s a short woodland ride from Myopia’s grounds, where the club’s fall-season opening match will be held on September 22.

Besides polo, the sprawling museum show covers dressage (performance of a precise series of movements), foxhunting, and the resurgent Gilded Age coaching revival (with harnessing and driving tournaments), along with displays of saddles, bridles, and garb, horse-themed vintage games and toys, and a play paddock for children. Gwinn notes as well that the North Shore played a significant role in American eventing, also known as horse trials. Generally comprising dressage, show-jumping, and cross-country, eventing is rooted in historic military competitions during which officers showcased their cavalry horses’ “obedience, maneuverability, and endurance.” In 1973, Myopia club polo player and huntsman Neil R. Ayer Sr., M.B.A. ’54, established a world-renowned eventing course on his family’s Ledyard Farm, in Wenham—vestiges of which remain. It was the site of numerous Olympic pre-trials; England’s Princess Anne and her then-husband, Captain Mark Phillips, competed there in 1975.

The museum highlights the 1910 union of another Ayer family member, Beatrice Banning Ayer, and a young U.S. Army lieutenant named George S. Patton Jr.—the future four-star general. In 1928, they moved into a South Hamilton homestead, with 27 acres of fertile fields and horse trails along the Ipswich River, that became their family base—and then that of their son, George Smith Patton IV, a highly decorated U.S. Army major general in his own right. (His widow, Joanne Holbrook Patton, donated the property and family archives to the town of Hamilton and the nonprofit Wenham Museum, respectively; both are now open to the public for guided tours, by appointment only.) The famous World War II commander “was raised on a California ranch,” Gwinn says, “and was one hell of a rider and polo player.” In a quote from the exhibit, Patton clearly savored the “virtue of polo as a military accomplishment….It makes a man think fast while he is excited; it reduces his natural respect for his own safety—that is, makes him bold.” His wife, Beatrice, who grew up in Boston’s Ayer Mansion, was also an expert competitive rider, as were other family members, and is featured in the exhibit’s montage of Patton family home movies narrated by their son.

Harvard connections to the region’s equestrian community run deep, as the exhibit reveals. Myopia’s predecessor, Myopia 9, was a baseball club formed and named, half-jokingly, by a group that included four near-sighted sons of Boston mayor and steeplechase racer Frederick O. Prince, A.B. 1836. They all played baseball at Harvard, and built the original club house in 1879 in Winchester. Many in the group, however, soon became infatuated with fox hunting. By 1883, the club was officially re-christened Myopia Hunt Club and relocated to South Hamilton, where members brought a pack of hounds over from England and purchased the Gibney Farm (its main building still serves as the clubhouse) with Harvard polo player Randolph M. Appleton, A.B. 1884, serving as Master of the Hounds from 1883 to 1900. Since 1952 the club’s hunts, which currently run through numerous open-land trails, from Essex and Ipswich to Newburyport, have been “drag hunts”: they follow a pre-laid scent instead of live prey.

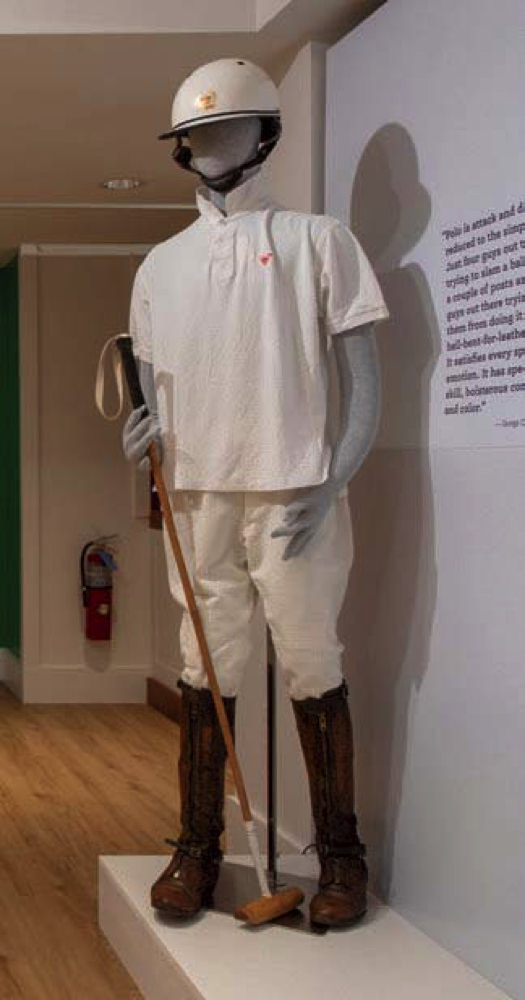

Polo, perhaps the world’s oldest team sport, took root in America in the 1870s, and spread to Danvers, Wenham, and Hamilton, the exhibit notes, where spectators arrived “by train, carriage and coach” to enjoy “half-time teas and divot-stamping—but it was the breathtaking speed and the ever-present possibility of risk that gave polo its loyal local following.”

All set for polo

Harvard played an integral role here, too. It formed the first United States intercollegiate polo team in 1883, and in 1890 moved its ponies and operations to land offered by Myopia; the two clubs were among the five charter members of the U.S. Polo Association in 1891. After a decades-long up-and-down history during the second half of the past century, Harvard polo revived in 2006 largely through “horses, a stable, and financial support,” the exhibit notes, from famous actor Tommy Lee Jones ’69, a veteran polo player himself. Its Hamilton equestrian center, a refurbished historic horse farm, opened in 2014.

Although American polo and other equestrian sports are typically expensive, rarefied pursuits, these traditions have influenced the regional character of the North Shore, affecting its residents, economy, and topography. In developing this new exhibit, the Wenham Museum—best known as a family-friendly place with an extensive model-train gallery and collections of antique dolls and toys—is building on its mission to “share local histories that continue to have a connection to and important impact on current and future generations,” Gwinn says. “‘Equestrian Histories’ offers a fun look back at the origins of horse in sport in New England—and beyond—and vivifies, for all ages, the universal values of sport activity, animal appreciation, and ongoing preservation of today’s North Shore landscapes.”