City on a Hill: Urban Idealism in America from the Puritans to the Present, by Alex Krieger, professor in practice of urban design (Harvard, $35). Americans romanticize the pastoral countryside and clustering in suburbs, but cities—and visions of better urban places—are threaded through their imaginations and experiences. Krieger, a distinguished practitioner-scholar (and member of the steering committee for Harvard’s urban development for its vast Allston holdings), surveys the history and expression of this vision, comprehensively and vividly.

The Puritans: A Transatlantic History, by David D. Hall, Bartlett professor of New England church history emeritus (Princeton, $35). Turning to that other “city on a hill,” Hall anchors Puritanism in its roots in Elizabethan England and Scotland, follows its migration to the more hospitable New England, and traces its religious and political decline. A sweeping, vigorous narrative, drawing on a lifetime of scholarship, it begins, briskly, “When Christendom in the West was swept by currents of renewal and reform in the sixteenth century, the outcome was schism.” Who would not read on?

Kinds Come First, by Jerome Kagan, Starch professor of psychology emeritus (MIT, $30). A seemingly technical book about the validity of experiments and their results, this volume makes a most humanistic point: Kagan argues that “a particular value on a reliable measure” probably does not possess “the same theoretical meaning for human participants who vary in developmental stage, gender, social class, or ethnic group.” That is to say, per the subtitle, the categories of “age, gender, class, and ethnicity give meaning to measures”—especially important to remember in a data-driven age.

Here All Along: Finding Meaning, Spirituality, and a Deeper Connection to Life—in Judaism, by Sarah Hurwitz ’99, J.D. ’04 (Random House, $28). Seriatim experiences in losing 2004 and 2008 presidential campaigns, and then eight years speechwriting in the White House, might drive anyone to contemplate her inner life. Hurwitz’s approachable account of her rediscovery that she did, indeed, “love Judaism enough to choose it back,” might find wide appeal.

Why Trust Science? by Naomi Oreskes, professor of the history of science (Princeton, $24.95). A scholar who has probed attempts to sow skepticism about science (by, among others, the tobacco industry and fossil-fuel producers), makes a strong case that science is credible precisely because it is a social, human process. (See Harvard Portrait, July-August 2014, page 23.)

Usual Cruelty: The Complicity of Lawyers in the Criminal Injustice System, by Alec Karakatsanis, J.D. ’08 (The New Press, $24.99). A public-interest lawyer who is a fierce critic of “human caging” and money bail (read “Criminal Injustice,” September-October 2017, page 44, profiling his Civil Rights Corps) here republishes some of his foundational essays, including the recent “The Punishment Bureaucracy”—a sharp critique of what he sees as the flawed, limited premises of the movement for “criminal justice reform.”

Virtue Politics: Soulcraft and Statecraft in Renaissance Italy, by James Hankins, professor of history (Harvard, $45). The founding editor of the I Tatti Renaissance Library (see “Rereading the Renaissance,” March-April 2006, page 34) undertakes a magisterial reassessment of the humanist political thought of that momentous upwelling. He finds that the focus on Machiavelli and the machinations of statecraft underplay the focus on character, virtue, and the shaping of the citizenry (through education in the humanities). Hankins’s project began before its relevance to contemporary politics could have been dimly perceived, and, one may hope, will long outlive the dilemmas of the moment.

The Great Democracy: How to Fix Our Politics, Unrig the Economy, and Unite America, by Ganesh Sitaraman ’04, J.D. ’08 (Basic Books, $28). The professor of law at Vanderbilt, operating on a less philosophical level than Hankins, takes stock of the neoliberal era that began in the 1980s and that he now perceives as “collapsing.” The contending visions for “what comes next” are “reformed neoliberalism” (more of the same, tweaked), “nationalist populism,” or authoritarianism: “nationalist oligarchy.” Finding those options grim, he advocates “a new era of democracy,” with vastly more civic engagement and institutions responsive to public, not private, interests.

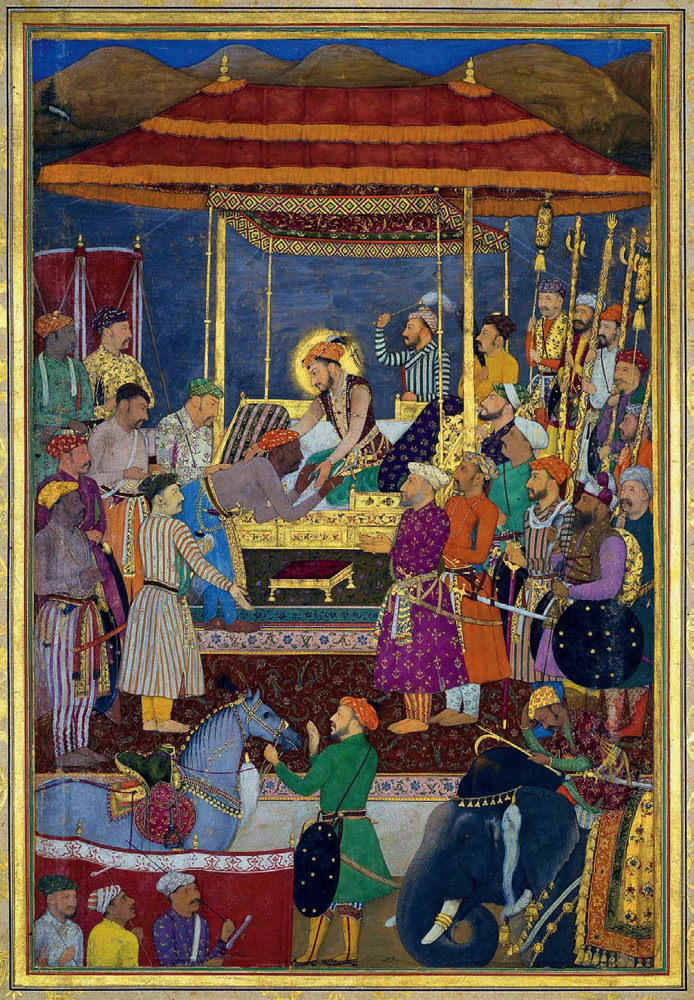

A consequential Mughal victory: a gemlike depiction of the submission of Rana Amar Singh of Mewar to Prince Khurram, the future Shah Jahan, on February 5, 1615

Photograph courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India, by Supriya Gandhi, Ph.D. ’10 (Harvard, $29.95). Why a history of the eldest son of Shah Jahan, the fifth Mughal emperor, who commissioned the Taj Mahal? If only to recall India’s full peopling and cultures, at this moment of intense, and increasingly exclusionary, Hindu nationalism. The author is now senior lecturer in religious studies at Yale. Her graceful account does not shy from the tensions that have inhered in the subcontinent for a millennium.

Three Poems, by Hannah Sullivan, Ph.D. ’08 (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $23). The author, associate professor at New College, Oxford, where she is a scholar of English modernism (Henry James, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, et al.), now crafts her own poems. The plain title hints at what is within: long poetic meditations prompted by the ordinary objects and scenes that launch memories and scaffold lives.

A New World Begins: The History of the French Revolution, by Jeremy D. Popkin, A.M. ’71 (Basic Books, $35). The Bryan Chair professor of history at the University of Kentucky, who grew up during the convulsions of the 1960s, crafts a narrative history of the revolution, two centuries and three decades after its convulsive beginning raised, indelibly, the persisting issues of liberty and democracy.

Moving Up without Losing Your Way: The Ethical Costs of Upward Mobility, by Jennifer M. Morton (Princeton, $26.95). The author, an associate professor of philosophy at CCNY and now UNC-Chapel Hill, reflects on what it takes, and costs, to move from one stratum of society to another as a first-generation student at elite colleges: in her case, from birth in Lima, Peru, through a Princeton undergraduate education and a Stanford doctorate. At a time of increased focus on such students’ needs (see Anthony Abraham Jack’s research, “Adjacent but Unequal,” March-April 2019, page 26, and the College’s First-Year Retreat and Experience, harvardmagazine.com/fyre-18), this welcome exploration deepens understanding of the real challenges.

The Affirmative Action Puzzle: A Living History from Reconstruction to Today, by Melvin I. Urofsky (Pantheon, $35). The professor of law and public policy and of history emeritus at Virginia Commonwealth University, a leading Brandeis scholar, has performed the useful service of delivering an even-handed, comprehensive survey of the subject—about which he was and is “conflicted.” The chapter on higher education necessarily deals extensively with Harvard, from the Bakke case to the recent, if preliminary, victory in the Students for Fair Admissions lawsuit (“Harvard’s Admissions Process Upheld,” November-December 2019, page 21). But it is worthwhile thinking about the whole field for a more than parochial perspective on what remains fiercely contested terrain.