In Norman Juster’s children’s book The Phantom Tollbooth, the land of infinity can be reached by following a line drawn on the ground for all eternity, then taking a left at the end. Fortunately, for viewers in a hurry, an exhibition now on display on the first floor of the Science Center offers a shortcut. Cabot professor of mathematics, Curtis McMullen, chair of the department, has created a series of nine prints, Negatively Curved Crystals, in part to illustrate how research mathematics sees the infinite. For mathematicians, McMullen’s images are themselves discoveries—as much a part of the research process as the proof of a new theorem. For everyone else, these prints are beautiful works of art, interwoven tapestries of lines and curves that build slowly into shadowy geometric forms, some only visible at a distance. Each image is the trace of an infinite process, left behind for us finite beings to admire.

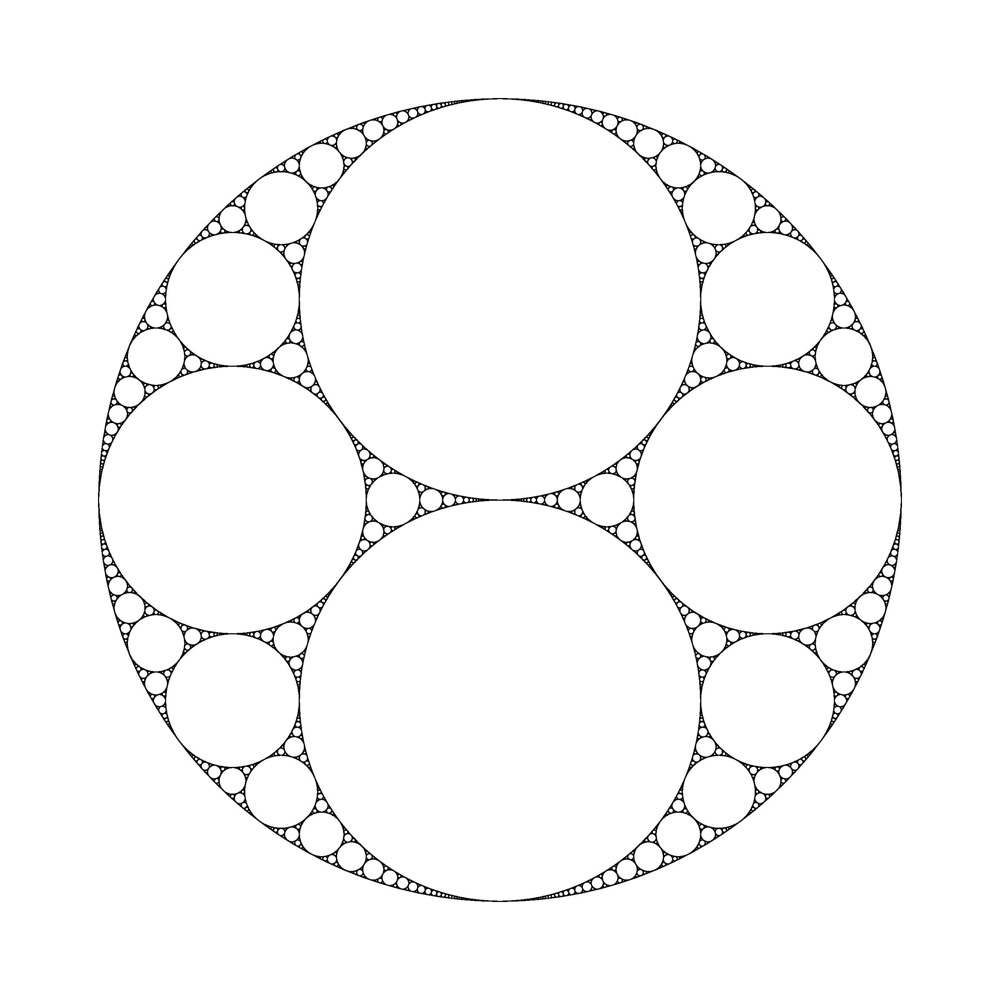

McMullen began drawing images like these with a computer program he wrote in the 1990s—his colleagues had been imagining certain mathematical patterns for years, proving facts about their structure and form, but had never seen them with their own eyes. Each print in the exhibition is generated from a geometric rule, some simple enough to be familiar to any avid doodler. Although I didn’t recognize the name, when I saw McMullen’s rendition of what mathematicians call the “Apollonian Gasket,” I felt an immediate spark of recognition: I drew the same thing out of boredom in one of my high-school notebooks. The image is a fractal, meaning that you can zoom in infinitely far on parts of the image and still see similar patterns emerge. McMullen created the print by packing smaller and smaller circles together in vanishing free space, creating an intricate pattern out of a basic notebook game.

Image by Curtis McMullen

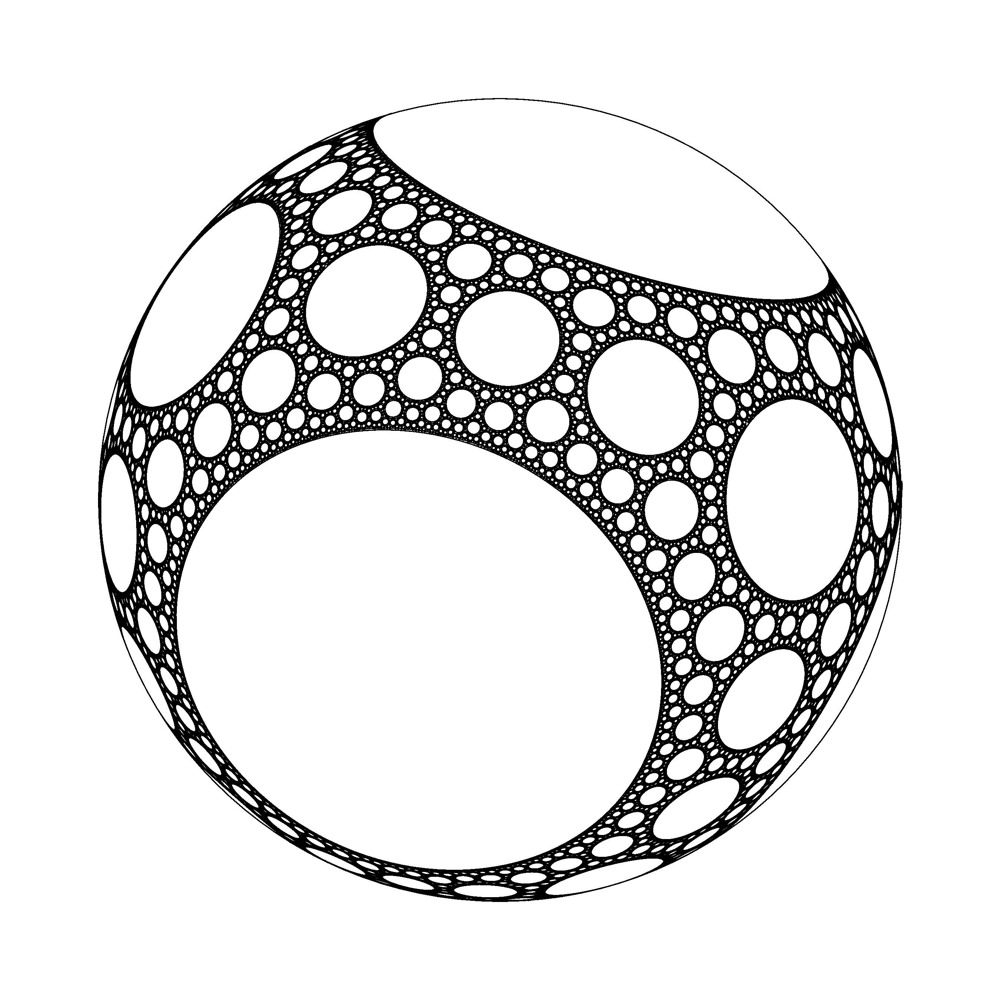

When McMullen talks about mathematics, I get the feeling that he sees it all a bit like a Bach suite: endless variations twirling around a simple theme. Inspired by the basic print above, where the circles all touch each other at a point, McMullen wanted to see a portrait of interwoven circles where none of them touch at all—an infinitely complex circular slice of Swiss cheese. “People knew mathematically that these patterns should exist, but they had never seen one before,” he explains. “So, for me, this was like discovering something or visualizing a new physical or astronomical phenomenon.” He blew the pattern up onto a sphere, a bit like a celestial globe displaying the constellations in the night sky.

Image by Curtis McMullen

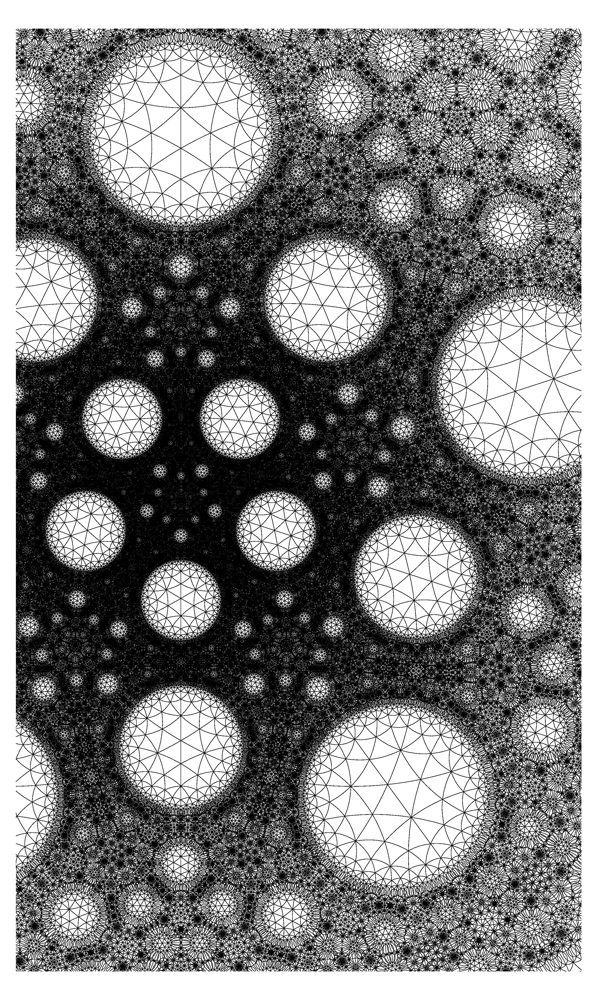

Each of the other prints follows its own internal set of rules. Many are generated by a simple pattern of lines reflected many times, the way two mirrors across from one another create the appearance of a tunnel extending infinitely far into the distance. All share a complex relationship to what mathematicians call “negatively curved space”—an exotic place where normal geometric rules like the Pythagorean theorem no longer apply. But despite all the mathematical rigor behind his prints, McMullen has decided against explaining how he created the images in his exhibition. “People often have a negative reaction to the word ‘mathematics,’ right? I didn't want to push that it was mathematics. I didn't want to say what it was at all,” he says. “I just wanted it to be something for people to look at and discuss.” Some viewers have told him that his prints resemble rugs, or X-ray crystallography, or shorelines viewed from an airplane—an ambiguity McMullen enjoys.

Image by Curtis McMullen

Like many artists, McMullen seems drawn to creating things—as if he has no choice but to build intricate patterns out of curves. As he tells it, the print series was a kind of outlet for this restless process of creation. “I was putting them on my refrigerator; I was putting them on the bulletin board; and I wondered how I could exorcise this from my life,” he says.