For a three-year-old Malaysian girl, the “magic hour” came in the heat of the afternoon, when everyone else in the small white bungalow was resting. She’d stand at the window, watching in wonder.

“The world is full of this shimmering heat, a tropical dream,” she recalls. “This old house that is basically falling down and is surrounded by the jungle. There were monkeys and wild chickens and other animals out there.”

The girl held that experience close as her family moved to cities in far-off lands like Japan and Germany for her diplomat father’s work. (Her mother, a Chinese school teacher, couldn’t work while they were abroad.) At each stop she was the new kid, always the foreigner on the outside looking in. She carried the images with her when she crossed the ocean to America, where she graduated from Harvard, worked in the corporate world as a management consultant, then moved to California, where she lives now, and had two children of her own. Along the way, as a stay-at-home-mom, she started translating those childhood memories—not the specifics, but the magic, the wild lushness of a mysterious world—into words, into stories. Yangsze Choo ’95 became a novelist.

Initially, she wrote simply for herself. “For a long time, writing was my secret life,” she says. “I never thought I would get published.” Her first novel was a first-“person” tale told by an elephant-detective (yes, you read that right); it collapsed under the weight of that concept and remains hidden away for eternity.

Her first published book, The Ghost Bride, released in 2013, tells the story of a young girl forced to marry a wealthy but dead boy in a “spirit marriage.” The novel became an Oprah.com selection and a New York Times bestseller and debuted early this year as a Malaysian-language Netflix series.

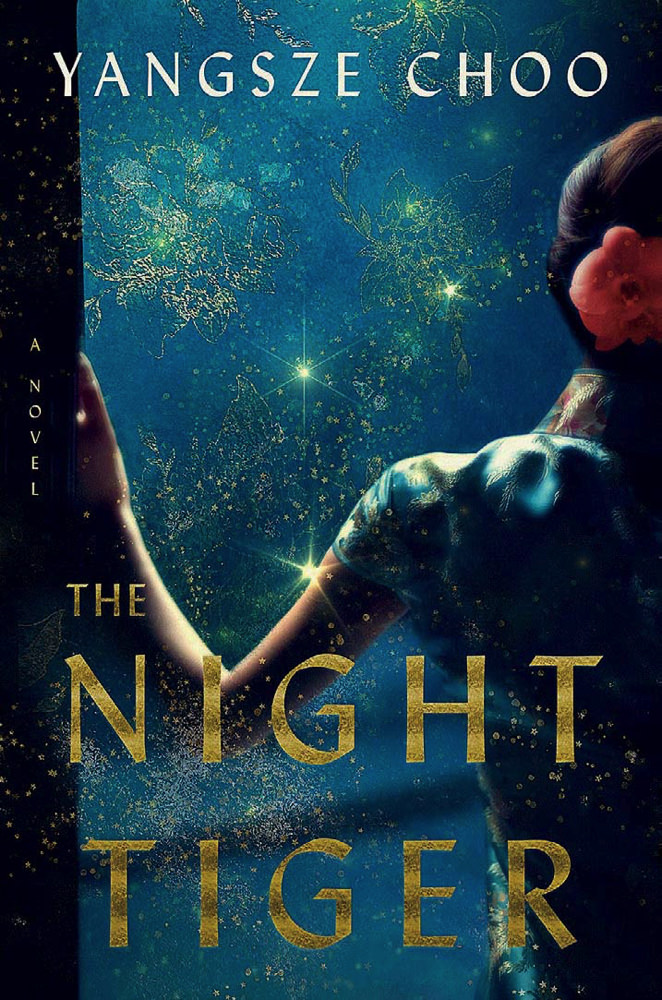

She returned in 2019 with The Night Tiger, another well-received bestseller; Kirkus Reviews declared it “a sumptuous garden maze of a novel that immerses readers in a complex, vanished world.” The book is set in what was then British Malaya, in 1931; it’s a riveting, luminous tale that splits the narrative between Ji Lin, a dance-hall performer whose ambitions are stunted by societal sexism and a strict stepfather, and Ren, an orphaned houseboy for two British doctors with a decadent taste for the exotic. There are mysterious deaths and rumors of a legendary “weretiger” that’s part-man, part-beast; a deathbed request by one of his masters sends Ren in search of a severed finger. Choo lets her characters follow their own paths. “I wind them up and they go,” she says. So while Dr. Acton, one of the Englishmen Ren serves, is a metaphor for colonialism, he’s also a complete character, with charms and flaws. Choo says he’s a variation of a Silicon Valley “tech bro” in his obliviousness to his own privilege.

“It’s a historical novel, but the themes are incredibly relevant,” says Caroline Bleeke ’10, a senior editor at Flatiron Books who worked with Choo on The Night Tiger. The novel explores colonialism, power dynamics, gender, and class, and the narrative pulses with peril for both protagonists, thanks to what Choo calls “a big dolloping heap of Agatha Christie” with a touch of the supernatural.

In a broader sense, her literary models include Haruki Murakami, Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red, and Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, “all wonderful stories of new and strange worlds interspersed with the ordinary.” She also reached back to her childhood, reading historic traveler’s tales about Malaysia by Isabella Bird and R.H. Bruce Lockhart. There was also some Somerset Maugham lying around her family’s house, including short stories, set in 1930s colonial Malaya. She was too young to fully grasp them, so “I put some of that feeling into the idea of Ren, the houseboy who is privy to a lot of grown-up secrets that he doesn’t quite comprehend.”

“Writing is like riding a bicycle at night with no lights. You never know what’s coming up, but when you’re on a roll, it’s wonderful.”

Despite the dark undercurrents (Ji Lin is filled with “an inky, twilight gloom” as events become “cold weights on a string of bad luck”), Choo’s characters are energetic and exuberant, much like their creator. She says those evocative phrases, and even the narrative arcs, just come to her. “Writing is like riding a bicycle at night with no lights,” she says. “You never know what’s coming up, but when you’re on a roll, it’s wonderful.”

Conversations with Choo tend to veer off into tangents: a question about her writing becomes a discussion of mice and rats, or raising kids, or chocolate, which she says is never far from her mind (or her hands) while she is writing.

Harvard was vital to Choo’s growth, and not just because she met classmate James Cham, now her husband, there. “When I arrived on campus, I had a feeling of tremendous relief. ‘Look, it’s full of nerds; it’s my people,’” she says, laughing. “I was always the nerdy kid in the library.” She concentrated in social studies, and vividly recalls a course on moral reasoning and Confucian ethics taught by Tu Weiming, then Harvard-Yenching professor of Chinese history and philosophy and Confucian studies. In The Night Tiger, she says, “Everything about Confucian values, how you cultivate yourself and how the self goes into the world, is from that class.”

Moving around shaped Choo’s writing, too—being uprooted meant always trying to blend in, which taught her to be a keen observer of her peers and what was or wasn’t considered cool. It also taught her to always embrace the new.

Still, her early childhood retains a strong hold on her: tigers, monitor lizards, and other wild creatures are essential to her novel (and many more were cut in editing). Her parents have returned to Kuala Lumpur and she visits each year, often doing research for the details that infuse her work with a deep and detailed sense of place. “Writing or reading a novel is like entering someone else’s vivid dream,” she says. “I had to build up a world with specific details, so readers feel like everything is there and it doesn’t get blurry.”