The “deplorables”—they are not the Other, they are ourselves. The best thing about Tightrope, an inspiring-but-frustrating book, is that it brings us up close and personal with America’s working class and poor: not as voyeurs, but as neighbors. Nicholas Kristof ’82, a New York Times columnist whose parents were professors, grew up in the white working-class town of Yamhill, Oregon, taking the bus to school with the children of janitors and farmworkers. He and his co-author and wife, Sheryl WuDunn, M.B.A. ’86 (they previously wrote about the oppression of women in less-developed countries; see “Women in a Woeful World,” September-October 2009, page 20), here set out to reveal and explain the devastation of America’s low-income communities. Their narrative is peppered with pictures and vignettes from the lives of those kids and the adults they grew up to be, adults who trusted the authors with their stories and photos. The result is heartbreaking but moving in its small details of people remembered, not just for the meth lab they ran but for the fact that they were genius mechanics or that time they destroyed the nest of yellow jackets. These are whole people, not statistics. In a book largely written for a more advantaged audience, the immediacy and drama of these portrayals force the question on readers: what happens when we consider all of our fates as linked together?

Visiting Yamhill, but also distraught African-American communities in Baltimore and in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the authors first report the destruction of low-income life in the United States: the high dropout rates, declining real wages, increases in incarceration and in single-motherhood, and shocking declines in life expectancy due to suicide or drug or alcohol abuse. Given the hollowing out of working-class jobs, a lack of vocational education, and a miserly social-welfare system, low-income people pay a great price for their mistakes, Kristof and WuDunn contend. “It’s a tightrope that I’m walking,” says Drew, trying to stay off drugs and out of prison so he can stay involved with his baby son. “And sometimes it seems to be made of fishing line.”

The crux of the problem, the authors tell us early on, is what they dub “social poverty,” which they variously refer to as loneliness, social isolation, an erosion of trust, and a loss of dignity and self-respect stemming from unemployment, educational failure, family breakdown, and social dysfunction. Clearly, this phrase is doing a bit too much work here to be useful, but I found it so felicitous that it stayed with me, hovering behind the stories they told.

Separate chapters cover the rise in incarceration, the origins of the opioid crisis, and the roots of homelessness. Although Kristof and WuDunn acknowledge “bad choices” on the part of their protagonists, we also hear unflinching accounts of reckless pharmaceutical companies and venal medical practitioners, corrupt business owners and manipulative politicians.

Here too are those optimistic Kristof portraits we’ve come to expect from his newspaper columns. We see “America’s Mother Theresa” using every trick she can think of to wrench black Pine Bluff teenagers away from the pull of gang life; a homeless Nigerian refugee and second-grader who became the 2019 state chess champion thanks to a teacher who saw his promise; someone who once brought free dental care to Haiti and Guyana and then expanded it to the poor people of Virginia and Tennessee; and the graduates of an intensive rehab program with a 96 percent long-term success rate. Kristof and WuDunn have a knack for finding and reporting stories of the good Americans can do, sprinkled throughout the book like breadcrumbs to lure us back into the light. Tightrope manages to chronicle our worst while reminding us of our best.

Nonetheless, the book is uneven. There are a few strange omissions. Race is not very central; it gets a few pages and some footnotes. Gender is virtually absent; at one point, the authors write, “Something about reproductive health makes politicians and local officials lose their reasoning faculties,” and this kind of wide-eyed “who knows” shoulder-shrugging had me gnashing teeth. Finally, a book that rightly attributes much of the sorrow it recounts to the collapse of working-class jobs hardly mentions automation. Yet automation has eliminated more jobs than outsourcing, many of them in working-class occupations in manufacturing and agriculture. If we are to take seriously the importance of work as the foundation for dignity and self-respect, then we have to analyze those jobs that are susceptible to technological innovation and change—those that rely on routine and predictable tasks —and train our workforce for the jobs we think will be left: those that rely on creativity and interpersonal skills.

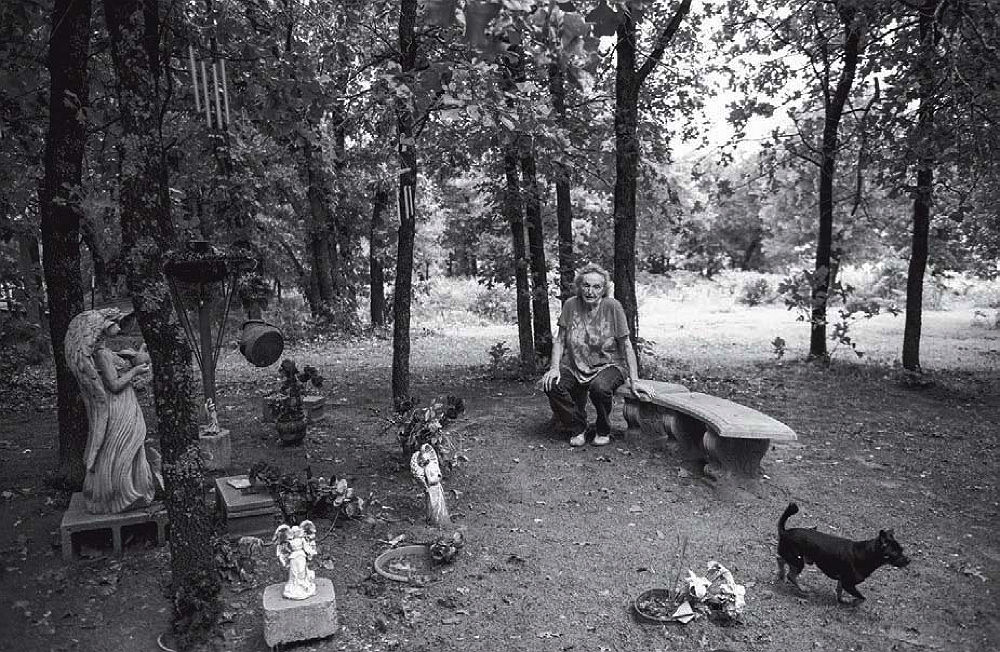

Dee Kapp visiting the gravesite of four of her five children

Photograph by Lynsey Addario

Most important, however, Kristof and WuDunn stumble particularly badly when they tackle the role of family dissolution in working-class lives, which they sometimes seem to argue is the cause rather than the effect of the collapse of low-income communities in America. I teach family sociology, and so I recognized the sources they quoted: writers who are certainly credentialed, but all selected from one side of what is actually a debate, all making the argument that “family structure matters.” The problem is that hidden in the term “family structure” are all manner of sins; by prioritizing marriage as crucial for children’s outcomes, it lumps together first, second, and third (and fourth!) marriages. It is this kind of marriage-at-all-costs fever that led to misguided government programs such as the marriage promotion campaigns begun with the 2002 Healthy Marriage Initiative. Such campaigns received more than a billion dollars of federal funding until randomized controlled trials proved it was an ineffective—and in some cases even counterproductive—strategy (some participants were actually more likely to break up). Studies have shown that it’s not that low-income people devalue marriage, but rather that they want to wait to marry until they have achieved a certain financial solidity. For some, that never comes.

Furthermore, as it turns out, what matters for most children’s thriving is not so much family structure as family stability; in other words, stepfamilies are not necessarily better than stable single-mother families. This was the central point of Andrew Cherlin’s heralded book The Marriage Go-Round and a host of other studies. Kristof and WuDunn actually pause in their paean to family structure to acknowledge this point, an admission strange in light of what comes before and after.

They openly wish for more working-class marriages as a way to save the men who are skidding out before our eyes; in one chapter we even see how such a rescue might work. But they really don’t consider what that means for the women involved, who would be married to—and thus in some cases in harm’s way of—the drug-addicted abusers they would need to save. We can see Kristof and WuDunn trying to resist the nostalgia for the working-class families of yore. Tightrope opens with an appalling story of Yamhill neighbor Dee Knapp in 1973, cowering in the back fields of her house in the dark while her raging drunken husband shoots his rifle into the brush, trying to hit her. The authors chose this story, they say, to counter any charge of wistfulness for the old days, when families stayed together and the working class had cause for its purpose, self-respect, optimism. They know that those days were difficult for women, African Americans, Latinos, and “others who did not even have a seat at the table.” Nonetheless, as the book progresses, they seem to forget their own counsel.

Their conclusion, too, is contradicted by their own stories. Several central protagonists, such as Clayton Green or Farlan Knapp, were raised by two-parent families, but lived lives wracked by tragedy and ended up among the so-called “deaths of despair.” Kristof and WuDunn celebrate the story of Ke’Niya, the youngest of 17 children in a poor but stable family, but she becomes a single mother herself while still in high school, even though she is “managing her young family, holding a job and starting college.” To be clear, I am not arguing against this celebration. There is good evidence that for low-income women, children can actually serve not as a tragic misstep, but instead as both tether and witness, a spur to jobs and further schooling. Ke’Niya is an apt representation of this phenomenon. “Especially when I had my son, it’s like, okay, now you don’t have a choice but to make something out of yourself,” she tells them. But clearly, “family structure” is too blunt an instrument for analyzing Ke’Niya, Clayton, or Farlan.

Instead, I think we can look for answers in “social poverty”—defined in a much more limited way to mean a thinness of social ties and the obligations they carry—and its converse, call it “social abundance.” It’s not that Ke’Niya’s parents are married that makes the difference for her future, which I agree seems bright, despite her single-motherhood. Instead it is the fullness of the social world in which she is embedded, a richly textured world of reciprocity and need, of accountability and promise, all the words that convey the ways we can be braided together. While dense social networks often come with judgment and surveillance, they can also provide a thicket of social support that helps to fortify us.

The social poverty that plagues the working class is in part internal to their communities: the fragmentation of families and relationships on which they can count—developments that certainly depend in part on material poverty, as well as scant jobs, spotty education, and an overeager criminal-justice system. (There is surely social poverty among affluent families as well, who are more likely to turn to the market to solve needs or problems.) But the concept of social poverty also allows us to talk about the changing definition of our communities in the first place: a large-scale shrinking from an “Us” to a “Them.”

The trouble with inequality is not simply the yawning chasm in material opportunities or outcomes that it generates, but also its cultural impact: the sense that our futures are not linked, that one group can bottom out without affecting the fortunes of the other. Tightrope can sometimes bolster the impression of a working-class America that is as distant as a foreign country. Kristof and WuDunn tell us that working-class men in the United States have the life expectancy of those in Sudan or Pakistan; that U.S. children living in “extreme poverty” would count as “extremely poor” even in Congo or Bangladesh; and that poor Americans have a homicide rate higher than their counterparts in Rwanda. The untold story here is the increasing sequestration of affluent people from the rest of the country, as schools, neighborhoods, even workplaces become increasingly segregated by class. Since the 1970s, the paths of these two Americas have diverged ever more widely. It is this divergence that makes the Yamhill stories unique, depicting a world in which different people connected not across the soup-kitchen counter or the courtroom, but across the fence.

Kristof and WuDunn might not employ “social poverty” in their analysis as much as I like, but their book, and its interweaving of the stories of their friends from Yamhill caught in the webs of misfortune, is an antidote to this sequestration, and thus deeply humane. “Whenever someone like Clayton dies an early death, whenever anyone falls from addiction, suicide, crime or despair, we all are diminished,” they write. And I believe them.