Ferguson, Missouri, the suburb north of St. Louis where 18-year-old Michael Brown was killed by police officer Darren Wilson in 2014, is also home to a multinational Fortune 500 company: Emerson Electric. After the U.S. Department of Justice released its long-awaited report on Ferguson’s police department in 2015, historian Walter Johnson was struck not just by the institutional racism it documented—how the city’s budget relied heavily on fines levied on its black residents for trivial infractions like jaywalking and parking tickets—but by the fact that so little revenue came from Emerson Electric’s coffers, and how that seemed so little talked about. “How is it that you can have a Fortune 500 company in a city where they’re farming poor black motorists for traffic tickets for revenue?” Johnson says. “It was surprising and outrageous. And it’s been surprising and outrageous to virtually every single person I’ve explained it to.”

“In a way, that was a question born of a kind of profound naiveté...about the way that cities work,” reflects the Winthrop professor of history and professor of African and African American studies. But it was the start of a project on St. Louis that would animate him in a way he describes as life-changing: “I’ve just become absolutely consumed with passion about St. Louis.”

St. Louis was once one of the nation’s largest and most important cities. It was the site of the 1904 World’s Fair, also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, a massive celebration of American imperialism in the city that was once the staging point for the westward expansion of the United States and the dispossession of Native Americans. There had been talk of moving the nation’s capital to St. Louis. The city is the home of institutions like Washington University in St. Louis, as well as Anheuser-Busch, founded by German immigrants in the nineteenth century, Monsanto, and McDonnell Douglas—all of which have now been bought by multinational firms. Three of the 25 wealthiest suburbs in the country are in metro St. Louis. Yet like many cities in America’s interior, it has experienced de-industrialization and dramatic population loss since the twentieth century; vast tracts of the starkly segregated city feel like a wrecked ghost town. “St. Louis today has the highest murder rate in the nation…and the highest rate of police shootings in the nation. There is an eighteen-year difference in life expectancy between a child born to a family living in the almost completely black Jeff-Vander-Lou neighborhood in North St. Louis and a child born to a family living in the majority-white suburb of Clayton,” Johnson writes in his new book, The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States (Basic Books). “[I]t is hard not to wonder: what happened here?”

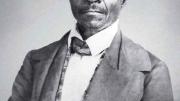

Walter Johnson

Photograph by Jim Harrison

St. Louis’s apparent contradictions, Johnson suggests, may not be so incongruous. His book takes what is already widely known about modern St. Louis and writes it into a new story of the city, from its imperial history to its contested role in the nineteenth-century battle over the expansion of slavery to its racist urban planning and development policy. His companion civic initiative, the Commonwealth Project, sends students to St. Louis to work with residents on the front lines of social struggles there.

Johnson gives voice to some of the most radical critiques of American history, and American capitalism, among Harvard’s faculty members. His work may sometimes sound abstract and intimidating, full of words like “racial capitalism” or “legibility,” but in person, he is open and effusive. “It was kind of a regular person’s upset that got me going on twentieth-century St. Louis,” he says. He’d been invited to speak at a Washington University conference in the fall of 2014, and though he’d always been a nineteenth-century historian, in the wake of Ferguson, he felt he couldn’t not address the rot that it exposed. It was an opportunity “to look at history, for me, in a new way—to do something very contemporary.”

In a 2015 story for The Atlantic, Johnson assumed the role of investigative journalist, writing about how Emerson Electric, despite conducting billions of dollar of business and having built a new, $50-million data center in Ferguson in 2009, paid the city only $68,000 in property taxes in 2014—a tiny fraction of what Ferguson earned from municipal fines—because of how its property was assessed. “The political economy of Ferguson and of what we call ‘economic development’ in St. Louis, in Missouri, and in the United States of America, around corporate tax abatement, is outrageous to normal people if you explain it to them,” Johnson booms. “But, for whatever reason, it’s also arcane. It’s hard to understand. It took me a long time to learn about it. I’m still anxious that I don’t fully understand it.”

“Walter really has a key piece of the puzzle that I think no one has grasped as brilliantly,” says George Lipsitz, a professor of black studies and sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “He correctly recognized that Emerson Electric paid about $68,000 in property taxes a year, but Ferguson collected $2 to $3 million in fines from residents, mostly from black residents. So the policing was not just an overt act of racial control, it was also an act of extraction from the poor in order to subsidize the rich.”

A native of Columbia, a mid-size college town where his father was an economics professor at the University of Missouri, Johnson made the two-hour trip to St. Louis frequently to visit family while growing up. He still speaks with a warm Missouri drawl. He wasn’t the most politically aware teenager, he says, but more than anything, he remembers being angry. “I started reading Kurt Vonnegut in eighth grade, and there was a notion that there was something that was wrong, that was sick, that was mean about our society. And that stuck with me. And it stuck with me as a kind of rage,” he says. “I could see everywhere, like, hypocrisy. All these people who basically said they were Christians and acted like jackasses....I could tell my town was segregated, and it made me angry that it was segregated, and everybody seemed like they were so pious about everything.

“I thought of myself, for a long time, that my goal was to be an antisocial person,” Johnson continues. “I thought, well, the way to respond to society being sick is to be different, kind of like a punk-rock impulse. To act out in school, be disrespectful of all rules and codes, break things, fight, drink.” In college at Amherst, where he started in 1984, he says, “I felt like really, really kind of an outsider there. I hadn’t figured out a way to channel my outsiderness into alliances with different sorts of outsiders. So I was kind of drunk and violent for a period of time.” He’s quick to add: “And, you know, still pretty into school. I was learning things, increasingly I was interested in ideas, but I hadn’t really imagined a larger version of purpose than simply acting out.” He was studying history, and became deeply interested in the relatively young field of “new social history”: “It was an effort to take seriously the ideas and aspirations of ordinary people.”

Johnson’s present interests and political convictions really began to take shape, he says, when he started his history Ph.D. at Princeton in 1989, under Nell Painter, Ph.D. ’74, a scholar of African-American history. “She really convinced me,” he says, “that if you’re going to really think about the history of working people in the United States, that you really needed to have a serious engagement with the question of African-American history and women’s history and, she always insisted…Native American history.

“I had a kind of intellectual, emotional commitment to ordinary people, and I had a lot of rage, and I had a definitely liberal anti-racism. I had a very strong Christian or liberal belief that all people are created equal,” Johnson remembers. “But it wasn’t really until I met Nell and began to learn under her direction that I think a lot of those commitments were put together into a more radical, anti-capitalist, anti-racist synthesis.”

For a long time, Johnson resisted the idea of writing about St. Louis. He had always focused on the links between slavery, capitalism, and U.S. imperialism that built the nineteenth-century American South. His 2013 book River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom distinguished him for a novel view of antebellum American history. It argued that the genocide of Native Americans in the Mississippi Valley paved the way for the expansion of plantation slavery and its development into a fully capitalist economy—with global ambitions. “For many, many, many years, when I got to 1865 in a book,” he says, “I could just close it and go on to the next book.”

But after Ferguson, Johnson began to see how his background in nineteenth-century history gave him a unique view into the twentieth and twenty-first. And into how St. Louis, for so long the imperial center of the expanding United States and a nexus of white supremacy and settler colonialism, became a place of such radical everyday violence. Some historians see St. Louis as a “representative city, a city that is, at once, east and west, north and south,” he writes in The Broken Heart of America. He thinks it’s better to see it as “the crucible of American history—that much of American history has unfolded from the juncture of empire and anti-Blackness in the city of St. Louis.”

“I came to this book less as a professional historian,” Johnson writes in The Broken Heart of America, “than as a citizen taking the measure of a history that I had lived through but not yet fully understood.” He traces the city’s racial politics to its origins as the military center for the expanding, imperial United States. One of the earliest episodes in the city’s history, as any St. Louis school child will learn, is the start of the expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, usually remembered as the great explorers who helped map the Louisiana Purchase territory. Johnson tells it differently: In 1804, he writes, Thomas Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark to “enumerate the Indians, announce to them the subordination of their nations to the United States of America, and gauge the economic potential of their lands.”

St. Louis, he continues, would soon become “the military headquarters of the Western Department of the US Army and the staging post for the Indian Wars. White settlers—backed by that St. Louis-based US Army but often operating well in advance of its lines—violently removed Native Americans from their lands all over the Upper Midwest.” During the second quarter of the nineteenth century, Johnson writes, Indian killing “became the (made in St. Louis) official policy of the United States in the West.” He describes the leadership of this period in St. Louis history, including the military leader William Harney, “one of the army’s most merciless and effective Indian fighters,” as belligerent, rapacious white supremacists. Yet they’re commemorated throughout the city to this day; Harney Avenue, Johnson writes, is not far from the site of Ferguson’s 2014 mass protests. Thomas Hart Benton, the U.S. senator from Missouri known for pushing westward expansion, is memorialized with a Roman-style statue in St. Louis’s historic Lafayette Square.

"There was no room at all for Black people—at least not free Black people—in the city of St. Louis."

Johnson argues that Native American removal also presaged a policy of “black removalism” that would characterize Missouri’s history from the very beginning. To understand why, it’s important to see how racism worked differently in the west (the frontier territory west of the Mississippi River) than it did in the south. Southern anti-blackness took the form of mass plantation slavery. “There’s a different story in the west,” Johnson explains, “where anti-blackness is much more tied up with, I think, the patterns and aspirations of empire. With the idea of ‘white man’s country.’ With getting rid of black people so that white people can rule the west in the absence of competition from slave labor, and particularly from free people of color.” Although there were slaves in St. Louis, there were far fewer than in other slave states—and there were many more working-class and non-slaveholding whites, who were militantly committed to clearing Missouri of Native American and black people. The “free soil” movement, which eventually merged with the Republican Party, thus opposed slavery not from an abolitionist ethic, but in support of a white supremacist vision of America. After the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which admitted Missouri to the union as a slave state, its constitution banned the migration of free people of color from other states. As Johnson puts it: “There was no room at all for Black people—at least not free Black people—in the city of St. Louis.”

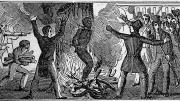

St. Louis, then, became a city that policed the mobility of free African Americans. Johnson writes that Francis McIntosh, a free black steamboat steward, in 1836 became “the victim of what was arguably the first lynching” in U.S. history when he was burned to death by a mob in St. Louis. In the Dred Scott v. Emerson and later Dred Scott v. Sandford cases, the St. Louis-based slave sued for the freedom of himself and his wife and daughters, arguing that they had spent time in Illinois and the Wisconsin territory, where slavery was illegal. The Missouri Supreme Court denied his claim in 1852, citing the state’s ban on free black migrants; subsequently, in 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court also ruled against Scott. “The Dred Scott decision reflected the politics of race and slavery in the city from which it emerged,” Johnson writes. It was about “extraterritorializing or even exterminating free people of color. It took the proslavery stance of the South and recalibrated it to the whites-only removalism of the West.”

Johnson’s view of history is animated by the concept of “racial capitalism,” an idea expounded by the late Cedric Robinson, a professor of political science and black studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. It refers not just to economic inequality between different racial groups, but to how, as he saw it, racial hierarchy is built into the very fabric of capitalism in the United States (and elsewhere). Racial capitalism, Johnson wrote in a Boston Review essay after Robinson’s death, is why modern economic expansion has been “dependent on slavery, violence, imperialism, and genocide.” It also is also why poor whites in Missouri, Johnson argues in his book, “were so arrested by the image of free Black competition that they could only dimly understand that they too toiled and suffered in the service of wealthy whites.”

Because working-class whites’ rage focused more on free black people than on the white elite, black removal continued in St. Louis long after the end of slavery. One of the most shocking anti-black massacres in American history broke out in 1917 in East St. Louis, the Illinois city across the Mississippi from St. Louis. The city had a growing population of black workers, often migrants from the south in search of opportunity. They held dirty, dangerous jobs in slaughterhouses and manufacturing plants, Johnson writes, “driving bolts into the brains of terrified animals on the killing floors; going unpaid during the ‘broken time’ herding new animals into the factory; tending the molten metal and carrying the castings and hot slag in among the furnaces in the metal plants, where the temperatures reached 120 degrees.”

Black workers were unwelcome in the local unions, and when the unions went on strike, employers would fire their members and recruit black workers for lower wages as strikebreakers—an example, Johnson writes, of racial capitalism’s two-tier labor system. Instead of organizing black workers, union leaders viewed them as an assault on the work and wages that belonged to white men. This is what happened when, in spring and summer 1917, workers of the Aluminum Ore Company went on strike. After the company hired black replacements, East St. Louis whites erupted in a terrifying spree of violence, beating, shooting, hanging, and burning the city’s black community. The massacre killed hundreds and left thousands more homeless, never to return to the city.

To this day, St. Louis is one of the most segregated American cities—by design. South of scenic Delmar Boulevard, the city is overwhelmingly white; to the north, it’s almost entirely black. A 1916 law banned racially integrated neighborhoods. Segregationist policies across the country were struck down throughout the twentieth century, but white citizens in St. Louis and elsewhere always found ways to keep black residents out of their communities.

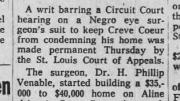

Johnson recounts one of the most stunning examples of the lengths to which white residents and institutions—including neighborhood associations, real-estate groups, and local government—went to make sure they would never have to live near a black person. In 1956, Howard Venable, an African-American ophthalmologist at St. Louis’s black hospital, began building a house on land he owned in the white suburb of Creve Coeur. White residents of Creve Coeur tried to persuade Venable to sell his land, a common practice used to keep black families out of white neighborhoods. But Venable refused. White residents eventually formed the “Citizens Advisory Committee on Parks” to persuade the city to force Venable to sell the property, or face condemnation. After battling the city in court for years, he lost. “Creve Coeur turned his land into a park, converting his single-story ranch-style house into a clubhouse for the city’s white citizens,” Johnson writes; the park was named for former Creve Coeur mayor John Beirne, one of the architects of the plan to strip Venable of his property.

Before seeking to move to Creve Coeur, Venable had been living in an area that was to be cleared to build a highway connecting the city to the white suburbs. Suburbanization spelled destruction for the city’s black communities: one of them, Mill Creek Valley, a historic neighborhood that had been home to 20,000 mostly black St. Louisans, was torn down as part of the city’s vision of post-World War II urban renewal, a process that St. Louis activist Ivory Perry called “black removal by white approval.”

Traditional accounts of American history often suggest a clean break between the pro-slavery movement of the south and the assumed anti-slavery commitments of a Union state like Missouri (where anti-secession forces eventually gained control); Johnson wants to complicate this pat narrative. “One of the things that I’m intent on,” he says, “is we have this huge conversation in our society about what are we going to do with the Confederate monuments? Well, what are we going to do with the Union monuments? I mean, what are we going to do with the monuments to all these Indian killers?”—men like William Harney, who was violently committed to white supremacy. “I feel like a lot of that history is either treated as uncanny—Wow, isn’t it weird that the Francis McIntosh [lynching] thing happened in St. Louis?…It’s treated as uncanny, or it’s just sort of forgotten.” Or violent episodes of the city’s recent history, like the destruction of Mill Creek Valley: “All these things, they’re like ghosts. They’re kind of known, but not really known.”

By the same token, Johnson adds, St. Louis’s history of black labor activism remains obscure even within the context of the city’s civil-rights history. During the Great Depression, he writes, “a radical and powerful working-class movement emerged in Black St. Louis, threatening both the hegemony of the middle-class Black civil rights organizations, like the Urban League and the NAACP, and the racial and economic order of the city.” A coalition of black workers and activists from the Communist Party, which was influential in St. Louis at the time, organized to improve conditions for wage workers; in 1933, 500 black women went on strike from their jobs at the Funsten Nut Company. Though many of them were arrested for protesting outside, within less than two weeks, they doubled their wages. With the decline of American communism during the Cold War, alliances between the black working class and the Communist Party faded. It wasn’t just the Red Scare that doomed the movement, Johnson writes, but also that the party was too preoccupied with converting black workers to communist ideology rather than meeting them where they were—“in the particularity of their own lives and beliefs.”

Part of what Johnson wants to do with the Commonwealth Project, he says, is to make St. Louis’s radical history more visible in the fabric of the city. The initiative grew out of conversations Johnson had with St. Louis rapper Tef Poe, who is known for his activism in the wake of Ferguson’s 2014 uprising, when Poe was a fellow at Harvard’s Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History. Founded by Johnson and Poe and housed at the Warren Center, the project now serves as an umbrella for a group of community-led collaborations between Johnson, students, and researchers at Harvard and St. Louis-based activists, artists, lawyers, and others. It aims to be “thoroughly mutual: to bring front-line knowledge into the university and university know-how into the community.”

“If you haven’t seen north St. Louis, you haven’t seen the United States of America. You’ve got to go see that to believe it.”

Last summer, Johnson took a group of students from his undergraduate course, “St. Louis from Lewis and Clark to Michael Brown,” to the city (a planned spring recess trip there this year was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic). “If you haven’t seen north St. Louis, you haven’t seen the United States of America. You’ve got to go see that to believe it,” Johnson says, referring to the absolute segregation and rows of abandoned lots. The city has started selling some of these properties, stamped LRA—Land Reutilization Authority—for $1 through its “Dollar House” program, to encourage buyers to fix them up. “As many books as I’ve written and as good as I’m reputed to be with using words, I can’t convey to anyone in writing what it’s like to be in north St. Louis.”

Two of his students—Kale Catchings ’22, who grew up in the St. Louis suburb of O’Fallon, and Saul Glist ’22—worked with the Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council (EHOC) last summer to build support for changing the name of Beirne Park, built on Howard Venable’s former land. By December, Creve Coeur’s city council had voted to rename it Dr. H. Phillip Venable Memorial Park, and had apologized for the city’s “abhorrent” past. “It’s just been amazing to see the speed at which this really took off,” says Kalila Jackson, a lawyer with EHOC. “There was no coalition formed when [Saul and Kale] came to us at the end of May, and by the time they left at the end of August, they had a coalition of at least six groups, including backing from several alderpeople, people in the city council...and Saul and Kale are wholly responsible for pulling that together.”

Across the river in Illinois, the Commonwealth Project is also working on a catastrophe currently devastating the poor, black city of Centreville just south of East St. Louis—“a little town that is gradually sinking in a flood of human waste,” as Johnson put it in a recent Boston Review essay. Its location in the Mississippi River floodplain makes it prone to inundation whenever it rains, and in recent years, the problem has grown worse. “Small fountains of raw sewage bubble up into the yards 24 hours a day, flowing into fetid sluiceways that run between the houses,” he writes. “Some days, especially in the summer, the whole town smells like an outhouse. And when it rains, and the water begins to rise, the sewage follows the water, out into the drainage ditches and the roadways, across the yards, into the houses.” One resident said that he “keeps a flatboat in his yard that he uses to ferry his neighbors when the water gets high.” This is a crisis, Johnson writes, “unfolding at the confluence of climate catastrophe, structural racism, infrastructural deterioration, and widespread indifference to black suffering.”

What can a Harvard professor and his students do to confront a situation so ruinous, and so vastly removed from daily life at an elite institution? One answer is to have some humility about what the role of an academic should be—and to not do what so-called experts have done in St. Louis’s past: simply justify the removal of people whose circumstances are inconvenient or embarrassing.

The Commonwealth Project has focused on researching the history of the situation in Centreville, conducting historical research to put together a press kit; Johnson also wants to gather oral histories from city residents (an initial plan to do so was delayed after the class’s spring recess trip was canceled). The idea, he says, is “to help people, first of all, to create an archive of the fullness of people’s histories and lives and humanity in the face of this catastrophe. They live in a catastrophic situation, but they have stories and aspirations that are not defined by that. And part of it is also to really create an archive of their connection to that place, because the goal is not, ‘Well, okay, this is a crappy situation, these people can be relocated to another place.’ This is their place. It’s the place that they’ve made their lives for decades. And so to create a kind of a historical record of that, to help make the case: no, this place needs to be changed.”

“Walter wants institutions to fulfill the promises they represent and to close the gap between word and deed.”

In many ways, Johnson still resembles his description of the younger, angry version of himself who was outraged by the world’s wrongs. At Harvard, he’s known for his vocal support of student and faculty activism, like the University’s graduate student union and its recent strike. “Whether it is Harvard or whether it is the state of Missouri or the United States federal government, he wants institutions to fulfill the promises that they represent and to close the gap between word and deed,” says a colleague, professor of history Kirsten Weld. “I think that he is just remarkably consistent in the way in which he articulates that moral demand, and he’s incredibly gifted at communicating its urgency…I can’t actually imagine how I would have survived at Harvard so far without Walter.”

Yet Johnson says he has only recently discovered how to harmonize his anger and his scholarship into a positive, loving way of engaging with other people. “I knew there was something deeply wrong with the way that I grew up, with the place that I was from. Then I went to other places, and they seemed, in a way, equally hollow and mean,” he says. “And then gradually, I think, finally now, really only now—I’m 52 years old—do I feel like all that stuff is going in one direction, with the books, the way that I’m thinking about the history of St. Louis, the work that I’m doing in St. Louis, the types of things that I can do with students, the way I’m trying to teach students. I feel like a lot of it is much more integrated for me than it has been in the past.”