We live in an age of ecosystems—of life threatened on a planetary scale by climate change—and of genomes—of life analyzed at the molecular level, unveiling our own evolutionary history and the processes that underlie all of biology. Powerful though these constructs are, if one’s views of biology, of life, are predominantly through the lenses of ecosystems and genomes, something has been lost.

I am an organismic biologist—a plant morphologist to be more precise. That means that when I think of a “unit” of biology, I am thinking about single organisms. I see individual plants, with their leaves spinning out in spirals defined by the Fibonacci series of fractional angles. I see their flowers for that instant of breathtakingly precise color, symmetry, and shape, all honed by selection to shed or capture pollen and yield the next generation. I watch as floral parts abscise and fruits are shaped to something approaching perfection for wind or animals to transport. I see bark with magnificent textures that range from smooth as paper to deeply furrowed. Yes, I know that individual plants are parts of complex ecosystems. I know that each tree is the product of the unbelievably complex and subtle interactions of the reading of the genetic code encased in every living cell of its body. But, for all of that knowledge, and for whatever nature and nurture have done to shape me, I yearn to see organisms—individual trees—to meet them, witness them, learn from them, and indeed, to age with them.

The wonderful thing about trees and other woody plants is that they do indeed age with us. I have watched a sapling bigleaf magnolia tree in my own backyard as it has grown from knee high to almost twice my height. I rejoice in each new leaf brought forth in the spring and early summer. I project ahead 20 years and imagine a magnificent tree with branches laden with platter-sized flowers and some of the largest simple leaves that can be found on a temperate tree. I am eager for this small tree to become a mature specimen—but also recoil at the notion that these 20 years will bring me considerably closer to my own maturity. On adult bigleaf magnolias, I watch the beetles pollinate flowers as they crawl across the female parts, laden with pollen. I envision next year’s leaves being born inside the protected tips of each shoot on the plant. I note the withdrawal of chlorophyll in the fall and the unveiling of deep yellow color throughout the crown of this tree. And in the winter, I take in the distinctive architecture, the “bones” of the tree, especially magnificent with an inch-thick coating of fresh snow.

I now practice my individual engagement with life—one plant, one person—at a particular place: the Arnold Arboretum, where I became director in 2011, well into a rewarding career as a professor of botany at the University of Georgia and the University of Colorado, teaching classes on the evolution and structure of plants, and conducting research on the evolutionary origin of flowering plants. Suddenly, I was surrounded by one of the world’s greatest collections of trees and other woody plants: 281 acres, designed by no less than Frederick Law Olmsted, where I could walk as often as I wished, if only I made time to do so.

After settling into my Arboretum and Harvard responsibilities, I found I had not made enough time for those walks. I resolved that I would never let a week go by without getting out onto the grounds to look at the roughly 16,000 accessioned woody plants that had beckoned me here from the Rocky Mountains. On every walk, I bring my small pocket camera and take pictures. Each night, I select the better ones, and spend additional time reflecting on what was revealed to me. And then, I share—typically three images and three paragraphs of text every few weeks. These Posts from the Collections, as I call them, are my attempt to help open up the individual plants I see to any and all, to draw readers into a new connection with nature—observed, not analyzed—through the myriad ephemeral moments of organismic beauty that surround us.

Collectively, the more than 100 Posts from the Collections that I have penned are a record of my random walks and interactions with the trees and other woody plants that reside at the Arnold Arboretum. These Posts are my way to let others in on the joys I have experienced as I have gotten to know non-human organisms on their terms: not as extensions of me, but rather as fellow living beings that can reveal their lives, history, complexity, beauty, architecture, and basic natural history if I only take the time to observe.

Anyone can make such observations, anywhere, under almost any conditions—as I happily hoped would be the case during the pandemic-constrained fall semester. To the students in my Freshman Seminar 52c, “Tree”—living in single bedrooms, under strict isolation, taking their classes remotely—the assignment to get outside each week and closely observe a single individual tree over the course of the semester provided a vital way to build a relationship with another organism and (safely distanced, outdoors) with fellow first-years. Their reactions, their photographs documenting what they saw, their perceptions of change within a single non-sentient tree during their 10 weeks in residence—all fostered connections to the larger, surrounding presence and rhythms of life when every circumstance seemed to conspire against doing so. As one student wrote, “This course has been one of the most transformational experiences that I’ve ever had. I came in expecting to learn about arborescence, but I ended up learning about myself, what it means to be human, and how to really see trees.” Indeed, trees have much to teach us.

As winter lifts, and as we hope our own isolation from the pandemic lifts, I hope in turn that by sharing some of these Posts more widely, here, I can encourage many more readers to see, and take pleasure, in the diversity of non-human organisms that surround us, as I have learned to do walking the grounds at the Arboretum, where nature unfolds to anyone willing to take the time to take it in.

• • • • •

Spruce cones dazzle

Photographs by William (Ned) Friedman

Over the years, I have come to view “spring coning” of conifers as having all of the same wonderful and ephemeral aspects of spring flowering (of flowering plants). There is temporal order among genera (larches first, pines last) and within genera (Siberian larch first); there is wonderful variety among taxa in size, shape, and color; there are also subtle differences between individuals of the same taxon.

In the last two weeks I have pursued the young (future) seed cones of the 25 species of spruce (Picea) that call the Arnold Arboretum home. For me, these are the conifer equivalent of magnolias—showstoppers at peak color on a sunny day. Even the quiet fortitude of the Norway spruce breaks stride and puts on a dazzling show of yellows, pinks, and deep crimson reds (Picea abies ‘Acrocona’; 475-36*B, middle image). Picea jezoensis (Yeddo spruce; 502-77*B, top image) in the dwarf conifer collection is always worth a pilgrimage. It is a tossup between the Koyama spruce (Picea koyamae; 15821*B, bottom image) and the Lijiang spruce (Picea likiangensis) for deepest blood red.

If you would like to see more spruces in full spring cone, head to ArbPIX. Here you will find cones from Picea abies (Norway spruce; Europe) to Picea wilsonii (Wilson spruce; central China), the endangered Picea chihuahuana (Chihuahua spruce; Mexico), and a host of others on full display.

May 17, 2020

• • • • •

Mountain laurels fling pollen

Photographs by William (Ned) Friedman

This week has been close to perfect when it comes to rhododendrons and azaleas at the Arnold Arboretum. Both belong to the Ericaceae, a family of plants that also includes blueberries, cranberries, and the mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia. The Arboretum has two stunning groupings of mountain laurels, and they are just beginning to get serious about floral display (middle image, from 2013). The first cluster is just down from the peak of Bussey Hill and is filled with a diversity of unique floral patterns created by the maestro of mountain laurel breeding, Richard Jayne. The second is just beyond Rhododendron Dell, on Hemlock Hill Road.

Beyond the clouds of flowers, the amazing thing about mountain laurels is the manner in which they disperse pollen. Have a close look at the large single flower above and you will see 10 curved filaments emanating from the center of the flower. These are the stamens, whose tips contain pollen. The brownish tip of each stamen can barely be seen since it is buried in a recess or “pocket” of the fused petals of the corolla. Ten stamens, 10 pockets. In the small floral bud, the stamens are originally straight, but as the flower expands, each stamen is bent backwards, creating (for the mechanically inclined) a cantilever spring under great stress. When a bee comes along (bottom), contact with the stamen releases the spring and pollen is flung, many inches, in the blink of an eye.

While picking flowers is strictly prohibited at the Arnold Arboretum, there are no rules against interacting with the stamens of mountain laurels. Bring a pen or pencil, and carefully tap against a stamen to see the results! I hope you will be amazed at what nature has wrought.

June 4, 2016

• • • • •

Killer magnolias

Photographs by William (Ned) Friedman

Everyone has heard of killer bees. But what about killer magnolias? That kill bees? Such is the case with the wonderful bigleaf magnolia (Magnolia macrophylla). For several years, I have been tracking this phenomenon at the Arnold Arboretum in the specimens growing amidst the hickory collection. So, how do I know that bigleaf magnolias kill bees?

Every June, I have a look inside the huge flowers (more than a foot in diameter when the tepals are fully reflexed). Lo and behold, there are frequently bees either in a state of stupefaction, flying erratically, barely moving, or not moving at all. Look closely at the large image above (top), a seemingly perfect picture of natural domesticity. A honey bee (blue arrow) is just about to alight on the reproductive parts of the flower to collect and be covered in pollen. Now look closely at the lower tepal (petal-like structure) and you will see a very dead bee (yellow arrow) surrounded by stamens (pollen producing organs) that have abscised. The middle image is a closeup of this scene, with ants (alive) going about their business. In the bottom image, a scene of carnage might not be obvious in the still life of a photograph, but the bee at the top of the cone-like female parts of the flower is paralyzed or dead, as are the two bees at left, and the bee at right (yellow dots). The bee on the bottom is very much alive, for now (blue dot). The appropriately named long-horned beetle (green dot) is moving along just fine.

How to make sense of a flowering plant that kills pollinating visitors? First, bees are not a major pollinator of bigleaf magnolias. I have never seen other kinds of pollinating insects killed by bigleaf magnolias—only bees. So, it is unlikely that these trees are killing their partners in reproduction (such as beetles). What we do know, so far, is that during the first phase of flowering, the female parts are covered by a liquid secretion for a matter of hours (this fluid helps the pollen germinate). The dead bees are always wet, and this secretion seems likely to be the toxic potion. Stay tuned. We have collected this secretion, and a chemical analysis will soon reveal the key to the killer bigleaf magnolias (which is the only species of magnolia that appears to kill bees).

July 7, 2018

• • • • •

Things are looking up!

Photographs by William (Ned) Friedman

Late October’s record snowfall in Boston, along with some seriously cold temperatures, put an end to many of the November fall-color all-stars at the Arnold Arboretum. There will not be lines of people queued up to take selfies in front of the Japanese maples (unless crispy brown leaves are your thing). Nevertheless, year after year, irrespective of what dame nature serves up, the oak collection always dazzles in late autumn. This year was no exception.

With 1,037 oak trees in the living collections (roughly 1 out of every 15 trees at the Arboretum), these venerable giants (and even the youthful recent accessions) dominated the landscape this past week. Standing on top of Peters Hill and looking across the Arboretum’s 281 acres out to the skyline of Boston, the undulating landscape was essentially a sea of evergreen conifers and a mosaic of the peak fall colors (reds, yellows, tans, browns) of oaks (third image).

For me though, the best vantage point for an oak in full autumn regalia is at the very bottom of the tree: looking straight up, taking in each tree’s unique jutting signature of branches in near silhouette, and catching the low-angled sun lighting up the crown. Here, three grand oaks: a red oak (Quercus rubra, top), a willow oak (Quercus phellos, middle) with breathtaking golds, and a black oak (Quercus velutina, bottom) accessioned in the second year of the Arnold’s existence, 1873, still going strong.

November 14, 2020

• • • • •

Lacebark pine (겜튄漑) at its peak

Photographs by William (Ned) Friedman

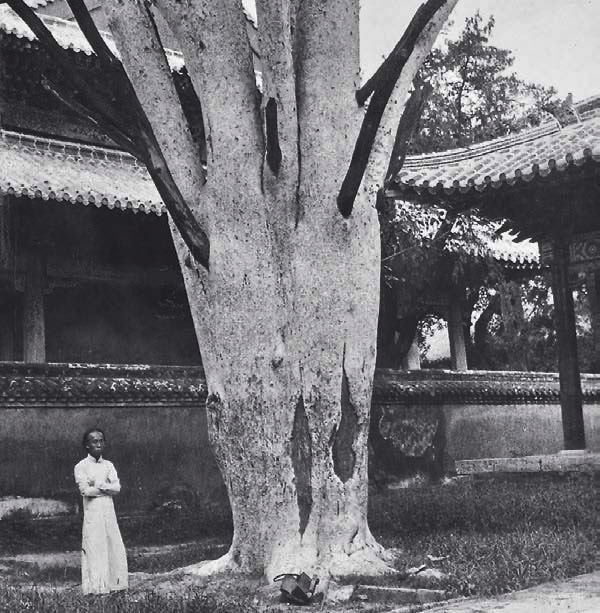

Yesterday, after the light rain ended, the sun broke through and beckoned me into the Conifer Collection at the Arboretum. With the still-wet barks glistening, everything from the firs (Abies) to the pines (Pinus) to the plum yews (Cephalotaxus) was breathtaking. But nothing can possibly exceed the dramatic bark of the Chinese lacebark pine (겜튄漑), Pinus bungeana. With bark that exfoliates in the winter in large puzzle-shaped pieces, colors that range from avocado to grapefruit rind, crimson, silver, lime and even a bit of peach can all be found interdigitating on a single trunk (top). Closer examination will demonstrate that the north and south sides of the trunk differ in their color schemes (north trends more silvery white). The odd thing is that descriptions and photographs (middle, by Arnold Arboretum explorer Frank Nicholas Meyer, September 7, 1907) of lacebark pine from China always note the milk-white bark. Perhaps our trees are just not old enough yet (Meyer estimated the tree in the image to be 1,500 or more years old).

As the older red bark (about to be retired from protecting the inner tree from the outer environment) peels away, it exposes the underlying greener (photosynthetic) younger bark, ready to do a year of duty. Look down, and you will see the puzzle pieces of bark among the shed needles (bottom image).

The Arboretum has nine lacebark pines, but my favorite specimen by far is one located just off Conifer Path 663-49*C; its bark is featured here. It came to the Arboretum in March of 1949 from our wonderful partners at Lushan Botanic Garden. On March 5, 2011, this tree was blown over in a winter storm. I was heartbroken. The next day, Arboretum horticulturists and arborists snapped into action, righted the tree, cabled it to a neighbor, and here we are, eight years later—a magnificent tree to behold in the winter. Make this a destination soon.

February 9, 2019

• • • • •

Acorns aren’t built in a day (let alone a year in many cases)

Photographs by William (Ned) Friedman

August is acorn watching time. While we tend to notice acorns in the autumn when they come tumbling down to earth, most of the action is in late summer. This past week, I have been targeting every oak at the Arnold Arboretum that has generously offered its acorns on lower branches. The amazing thing is how many of these future acorns (the fruit) are still not visible and are entirely enclosed by the cupule (the cap)! What gives?

Pictured are four species of oaks at the Arboretum. From top: Quercus variabilis (17631*B), the Oriental oak, native to eastern Asia; Quercus castaneifolia (239-38*D), the chestnut-leaved oak, native to the Caucasus; Quercus dentata (1590-52*B), the daimyo oak, native to eastern Asia; and finally Quercus acutissima (1257-80*A), the sawtooth oak, native to a broad swath of temperate Asia. The cupules themselves are beautiful and varied. The scale leaves for each species have different textures and colors. One of the most dramatic right now is the daimyo oak, whose cupule scales are edged by a red stripe!

Rest assured that by autumn, each of these cupules will sport a full-fledged acorn fruit. But, in the meantime, the mother tree has a lot of provisioning to do to fill the fruits. For now, enjoy the cupules, which are magnificent in their own right. And keep watching to see the amazing transformation of each acorn from a small hidden structure encased in a beautiful cupule to the mature embryo-laden vessel that gravity will release in the autumn.

Bonus information: Oaks either take one growing season to mature an acorn from a flower or two. In the case of the “biennial” species, these truly are among the slowest flowers/fruits in the world. Flowers open and pollination occurs in spring of the first year followed by seemingly very little else for another 12 months. Then, slow expansion of the cupule in the spring and summer of the second year. Finally, in mid-summer of year two, the future seedling is born and the rest is a mad dash to fill the acorn with food for this next generation. So, even though all four oak species pictured here are at relatively the same developmental stage right now, and will have full-sized acorns in just a couple of months, two of them, the sawtooth oak and Oriental oak, were born (bloomed) in May of 2019!

August 8, 2020

More ways to enjoy the Arnold Arboretum collections

Join William (Ned) Friedman on a virtual walking tour at arboretum.harvard.edu/walks/directors-tour or visit the Arboretum online at arboretum.harvard.edu. Sign up to receive Posts from the Collections at arboretum.harvard.edu/sign-up. This article’s online version contains accession numbers for some specimens highlighted in the text. Those numbers link to an Arboretum map indicating the specimens’ locations.