This past April, Bonnie Tsui ’99 broke two ribs in a surfing injury. She had stayed out too long on a wave at the beach near her house—riding it in, holding on to the motion and the water, trying to live in that moment for as long as she could. “And then the wave starts to break in front of me,” she says, “so I start to hop off the board but it got sucked up the wave face.” The surfboard went one way, her body another, and they collided again with a crack.

It was incredibly painful. But she somehow gathered her board and carried it up to the sand, and then up the beach to her car, where she got her wetsuit off and waited for her friends. Later, her husband took her to urgent care. “Broken ribs are a sign of a life well lived,” her friend, the author Christopher McDougall, consoled her.

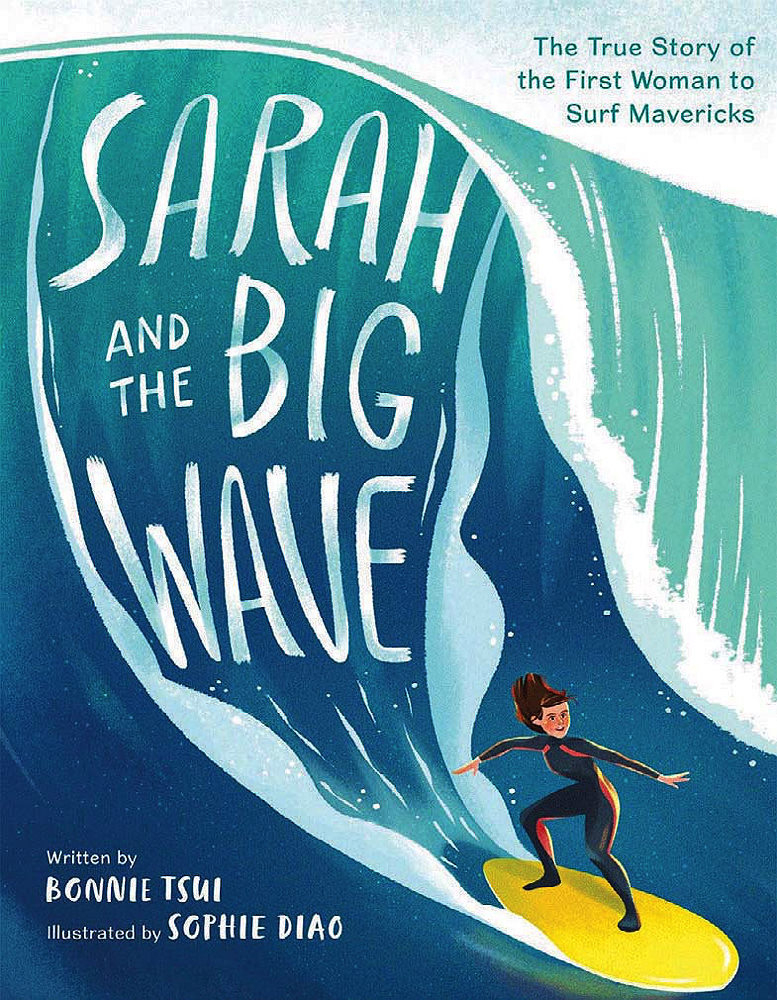

This is all very on-brand for Tsui, and not just because her latest work—Sarah and the Big Wave, released by Macmillan in May—is a children’s book about pioneering surfer Sarah Gerhardt. As an author, Tsui’s genius is pursuing ideas further than others might: riding a train of thought as far as it will take her, like a wave curling in toward the shore.

As a child, Tsui wanted to pursue a creative life, like her father’s. George Tsui, a prolific illustrator, painted movie posters, magazine illustrations, even Choose-Your-Own-Adventure book covers (in one, he appears as a haughty medieval emperor, while Tsui’s brother kneels at his feet). “I had the love of reading, writing, and art in my home,” Tsui says. “It was such a creative, expansive place.”

She inherited her dad’s gift for figure drawing—a portfolio of her art work helped get her accepted to Harvard—but she was also interested in writing. In college, she tried both, and found her calling in a literary nonfiction class taught by memoirist and author Natalie Kusz. “She changed my life,” Tsui says. “She taught me that writing nonfiction could be as exciting and inventive and voice-y and personally driven as fiction.”

It was a lesson cemented by an internship at a daily newspaper during a semester studying abroad in Sydney, Australia. To her delight, her editors sent her out to report and write articles from her first day. It was her first encounter with real journalism, and she was smitten. “I really love the part where you go out into the world and find stories,” she explains. “You can be curious about people and have the privilege of having them tell you amazing things that you would never experience yourself.”

One of her first assignments was a story about Sydney’s Chinatown. “I was out on the streets reporting, and this place is at once so familiar to me, people are speaking Cantonese, and yet it’s so different,” she recalls. She wondered how its history differed from Manhattan’s Chinatown, a place she was deeply familiar with; growing up, she wrote, it was where her family “went to be Chinese.”

Almost a decade later, that question became a book. American Chinatowns: A People’s History of Five Neighborhoods is a deeply reported examination of Chinatowns as a genre of civilization and a human phenomenon. Why, she wondered, did Chinatowns persist in American cities for generations after the first wave of immigrants settled them? What made them alike, and what made them so different? She would search the histories and citizens of each place for her answers.

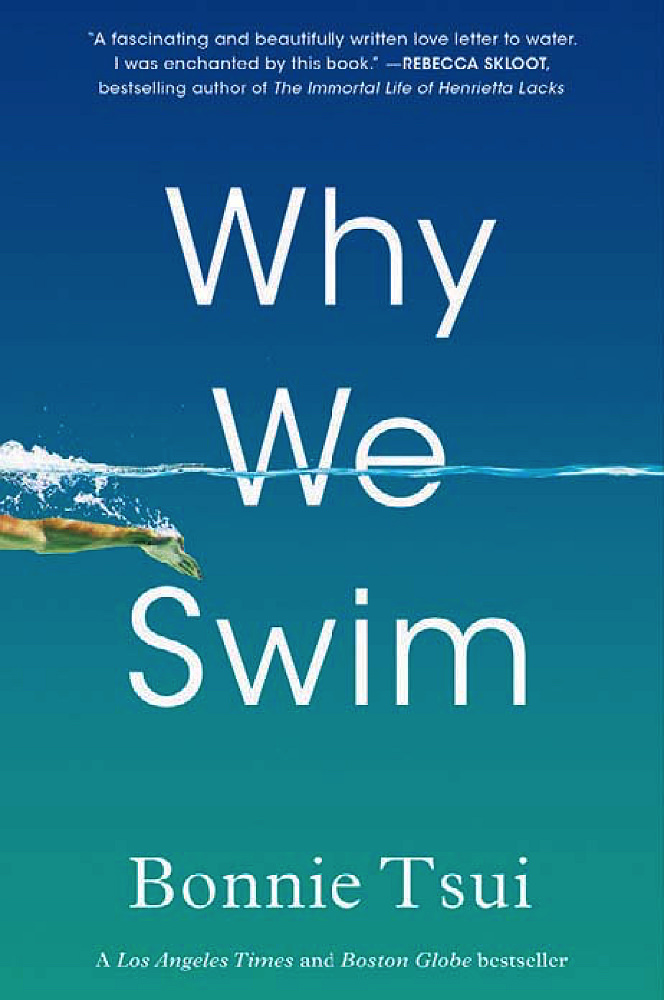

Her follow-up, last year’s Why We Swim, similarly framed the act of swimming—a lifelong pursuit and touchstone for Tsui—as a phenomenon to be studied. A competitive swimmer since childhood, she examined the history of humans’ relationship to the water, folding in science and archaeology, interviewing long-distance swimmers who brave extreme cold, dangerous currents, sharks, and other perils. Tsui also explored the ancient Japanese swimming martial art Nihon eiho and traveled to Iceland to meet with fisherman Guðlaugur Friðþórsson, who survived after his boat capsized and sank, swimming for six hours in 40-degree water.

“I really love the part where you go out into the world and find stories.”

Tsui’s love of swimming goes back as far as she can remember: “I felt the draw of liquid early on: that slide into lovely immersion, that spiraling weightlessness, that privileged access to a muted underworld,” she wrote. What, she asked, draws humans to the water over and over again, across millennia, for an activity that’s dangerous and for which we’re adaptationally ill-suited?

In both of her earlier books, “The subject matter was very personal to me,” she says. “I cared very much about the people or the place or the practice. But that drove me to examine and want to investigate, to interrogate the larger questions.”

Sarah and the Big Wave was more of a fluke: Tsui had always been interested in writing for children, but knew that market was tough to break into. Serendipitously, an editor at a Macmillan imprint for young readers saw an article she did for California Sunday Magazine on female big-wave surfers and got in touch. One of the swimmers she profiled for the magazine was Gerhardt, a chemistry professor who in 1999 became the first woman to surf the Mavericks, a northern California surf break where waves can crest as high as 60 feet.

Why We Swim came out just as quarantine was going into effect in April 2020; Sarah and the Big Wave arrives as vaccinations are easing pandemic isolation. Between the two, Tsui found an escape in swimming and surfing—and pondering her next book. “I’m thinking about all these kinds of things,” she says. “I’m really trying to let myself take the time to think about what that’s going to be. I’m open to any and all ideas.”

She does some of her best thinking in the ocean or the pool, but surfing and swimming are not an option with broken ribs. Instead, she says, she gets into the shower, just to feel the water flow over her skin.