Carolyn Gold’s memoir chronicling her long, slow recovery from a brain injury caused by West Nile encephalitis begins with a mosquito bite that she does not remember. It most likely happened sometime in August 2017, while Gold, M.Ed. ’85, was on vacation with her family on Martha’s Vineyard. A few weeks later, she fell ill, suddenly fumbling over her words during a meeting and then fading in and out of consciousness as friends rushed her home and her husband called an ambulance. Soon after, she was in the ICU, where doctors scrambled to keep her alive while trying to figure out what was happening: a bacterial infection? A virus? An autoimmune crisis? It took a month for the tests to reveal West Nile virus; in the meantime, Gold slipped into a coma and went on a ventilator and life support; at one point, her heart stopped, leading to a small stroke. Her fever hovered between 101 and 103 degrees. When, on day 10 of her coma, her husband agreed to let doctors wean Gold off of the ventilator, he prepared himself for the likelihood she would die. “You can imagine,” recalls Gold’s neurologist, James Hillis, who was a medical resident at the time, “that the discussions we were having as a team with her husband, Paul, were not the most promising from a prognostic perspective.”

Gold doesn’t remember any of this. In When I Died: Rx for Traumatic Brain Injury, which she self-published in 2020, she writes that her first memory after her initial collapse is of waking up in a stupor at Massachusetts General Hospital, confused and frightened. Those feelings would persist—along with others: anger, isolation, frustration, grief, despair—for weeks and months, as she struggled to recover, physically and cognitively. During a stay at an acute rehabilitation facility immediately after her release from the hospital, she was given high doses of steroids (intended to combat her brain inflammation) that left her disoriented, incapacitated, unable to tell night from day. “I felt insane,” Gold says of that time. “I would call my family in the middle of the night, screaming at them.” The first time she tried standing up from her wheelchair, her left leg shook uncontrollably. ““That’s your brain; it’s not your leg,’” the nurses told her. “And I thought, ‘What does that mean? Will it get better?’ And they said they didn’t know.”

Her next stop was a skilled nursing facility, where she began to improve more rapidly but also increasingly wondered if she’d ever be herself again. A few months earlier, the 72-year-old had been running her own management consulting company, serving on boards, organizing fundraising events. Now she couldn’t remember how to use her cell phone. “Whenever somebody would visit,” she says, “because I didn’t want to bomb people with too many questions—I’d ask each person just one question: ‘How do I make a phone call?’ ‘Where do I find people’s names and numbers?’ Eventually somebody showed me how to plug the phone in.” She couldn’t recognize the shower faucet in her room, even when it was right in front of her. “I searched for it for eight days,” she says. The problem wasn’t her eyesight, but her brain’s ability to process information. Finally, she asked for help from an occupational therapist, who suggested she search by touch rather than sight. Sliding her hands across the tiles, Gold felt the faucet, and then she saw it. “It was like magic,” she says. But it was also a painful lesson. “How come I couldn’t see it?” Gold asked the occupational therapist, “and she said, ‘You have brain damage. You have to accept that you aren’t able to scan a room and just look for something.’” After the therapist left, Gold cried for an hour. “Because I hadn’t accepted it yet,” she says. “I had disassociated from this brain-damaged person, who couldn’t find the faucet and couldn’t use a cell phone. I had joked about ‘my stranger.’”

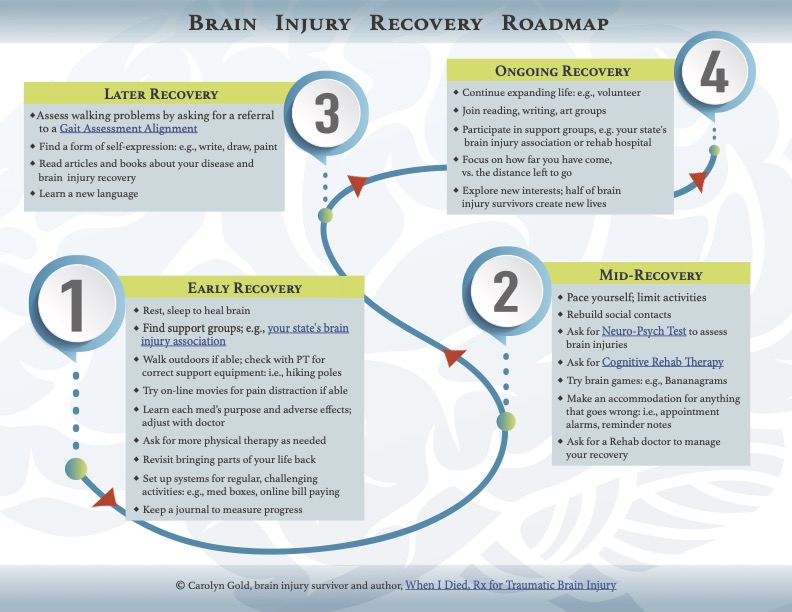

Drawing on her experience, Carolyn Gold designed a "brain injury recovery roadmap" to help guide other patients.

Graphic courtesy of Carolyn Gold

When I Died is full of anecdotes like this. Combining detailed personal narrative with plain-language medical information—which was fact-checked by Hillis—the book is meant as a resource for others who have also suffered brain injuries (and as a resource for their caregivers: the book’s final three chapters were written by Gold’s primary care physician, her speech pathologist, and her husband, each telling her story from their own perspective). Gold began writing it in late 2019, two years after she first got sick. By then, she had lots to share about illness and recovery: what to expect from one’s body and brain, where to look for help, how to deal with depression and grief, how to think about the toll on family and friends. Gold’s first days back home after rehab were some of the most difficult, she says. “Once you’re brain-injured, your whole purpose in life is gone. The hardest part was sitting here almost comatose in terrible pain, with my leg not working, not knowing if I’m going to get any better.” She remembers reading about the work of critical-care physician Daniela Lamas in a Harvard Magazine article and thinking, of Lamas’s post-ICU patients, “They’re my sisters and brothers. That’s exactly how I feel—I’m not dead, I’m not alive.” Encouraged, she found her way to other resources online: the Brain Injury Association of Massachusetts, and a now-defunct organization called Encephalitis Global. “You could ask questions, like, ‘Why am I sleeping 15 hours a day?’ ‘Why is my hair falling out?’ And they’d answer you. They said, ‘You’re getting better. You don’t notice it, but you are.’” Gold started measuring her progress: how far she could walk, how much conversation she could sustain, how many hours of the day she stayed awake.

Hillis remembers those early difficult adjustments, too. “One of the key things about people in Carolyn’s situation is just this sense of isolation,” he says. “When you end up in rehab or in the acute hospital, having lost all those faculties and functions you’re used to having, you feel so alone.” Patients are estranged from not only their former selves, but also from loved ones, who often cannot fully appreciate what the ordeal is like. “Now, having written her book, she’s brought it full circle, in a sense,” Hillis adds. “She’s involved in advocacy for brain injury patients, and she’s able to say to others, ‘You are not alone.’” And also to provide insights: “There are a lot of questions,” Hillis says, “that patients feel too embarrassed to ask—about normal bodily functions they’ve lost control of, for instance—and Carolyn’s book proactively answers those questions.”

Some of the book’s most moving sections are about coming to terms with the “stranger” she had become. “The brain-injured people I’ve met, a lot of them don’t come back to where they were,” she says. “I haven’t come back to where I was. I was the president of boards, I was doing huge fundraising—I can’t do anything like that now. If I try to do too much, my brain just shuts down.” She still sometimes has trouble summoning words, and without reminder texts, she misses meetings, even when they’re on her calendar. “I’d forget and be in the grocery store, and somebody would call me.” She still routinely forgets to stop at the mailbox when she and her husband are leaving the house, even when he reminds her as they’re getting in the car. “I say, ‘I’m going to stop at the mailbox, I’m going to stop at the mailbox,’ and then I drive right by. Some things can’t hold.”

One clarifying and helpful step she took was getting a neurophyschological evaluation. “It showed me exactly where my brain damage was,” she says: mainly in the frontal lobe, where executive functions like planning, attention, and decision-making are located. Armed with that knowledge, Gold began seeing a speech pathologist and started cognitive rehabilitation. “You have to either find another life that fits your capabilities, or learn how to adjust to what you’re missing,” she says. Gold has done a bit of both. Notes and reminders and other behavioral accomodations help her stay attentive and on task, but also … she’s no longer the driven professional she was a few years ago. She’s more patient now, more emotional and kind. One piece of her old life that still fits in the new one is her volunteer work in restorative justice circles, where empathy and patience are key. And instead of running a company, she’s now a certified spiritual director, helping other people with chronic illness.

That change was more gradual—yoga, long daily walks, Torah discussion groups, and a study of Jewish mysticism became a part of her recovery—but one important moment came about a year after she returned home from rehab. Cleaning out her bookcase, she says, “I noticed ‘who’ I had become: most of the books that remained were religious and spiritual. I even said to my husband, ‘Look who I have become!’ It was easier to let go of my old self when I had a new one to step into.”