Wayne Shorter, the 88-year-old, 11-time Grammy-winning saxophonist “generally acknowledged to be jazz’s greatest living composer” (New York Times), once said, “For me, the word ‘jazz,’ means, ‘I dare you.’” Last Friday, November 12, at the Cutler Majestic Theater in Boston, Shorter and Harvard professor of the practice of music esperanza spalding (who does not capitalize her name) brought that spirit to the opera world with the debut of …(Iphigenia), presented by ArtsEmerson and the New England Conservatory.

Shorter’s score and spalding’s libretto reimagines Euripides’s last tragedy, Iphigenia in Aulis. In the original myth, the goddess Artemis demands that Agamemnon, commander of the Greeks, sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, in exchange for favorable winds on their voyage to Troy. But in this reimagination—with set design by Frank Gehry, a cappella arrangements by Pulitzer-prize-winner Caroline Shaw, and direction by Lileana Blain-Cruz—Shorter and spalding “de-script” the tragedy, allowing a “multiplicity” of Iphigenias to imagine a new sequence of events.

In act one, the Greek soldiers sacrifice five separate Iphigenias, symbolizing both the ubiquity of the virgin sacrifice in myth and the “cyclical time of trauma,” according to the opera’s dramaturg Sunder Ganglani. However, in act two, the myth pauses for a moment and the previously sacrificed Iphigenias share their stories with the not-yet-sacrificed sixth Iphigenia (“Iphigenia of the Open Tense,” played by spalding), in the hopes that she can write a new ending. Finally, in act three, Iphigenia of the Open Tense is forced back into the story and, as Ganglani wrote, “offered the opportunity to let go of the myth and show us all how to make something else.”

Writing an opera about a Greek tragedy may seem a bit unexpected from Shorter and spalding, whose names are basically synonymous with two-generations-worth of jazz. Thirty-seven-year-old spalding, named “The 21st Century’s Jazz Genius” by National Public Radio, made a name for herself in as an upright bassist, composer, and singer with a talent for improvisation, but she entered the popular music consciousness when her classical-jazz fusion album, Chamber Music Society, won her the 2011 Grammy Award for Best New Artist (and beat out the favored-to-win Justin Bieber).

Since then, her work has spanned genres like funk and pop, but what seems to interest her most is sound itself. Her latest album, Songwrights Apothecary Lab, was designed with neuroscientists and music therapists to have healing effects on the listener, and she’s currently developing the Sonic Healing Lab at Harvard with a similar aim. Shorter’s work is equally undefinable. He was integral in many of jazz’s greatest groups and moments—first as the primary composer of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, then as the “intellectual musical catalyst” of the Miles Davis Quintet (according to Davis)—but he brought jazz into new territory with his group, Weather Report, that pioneered jazz fusion.

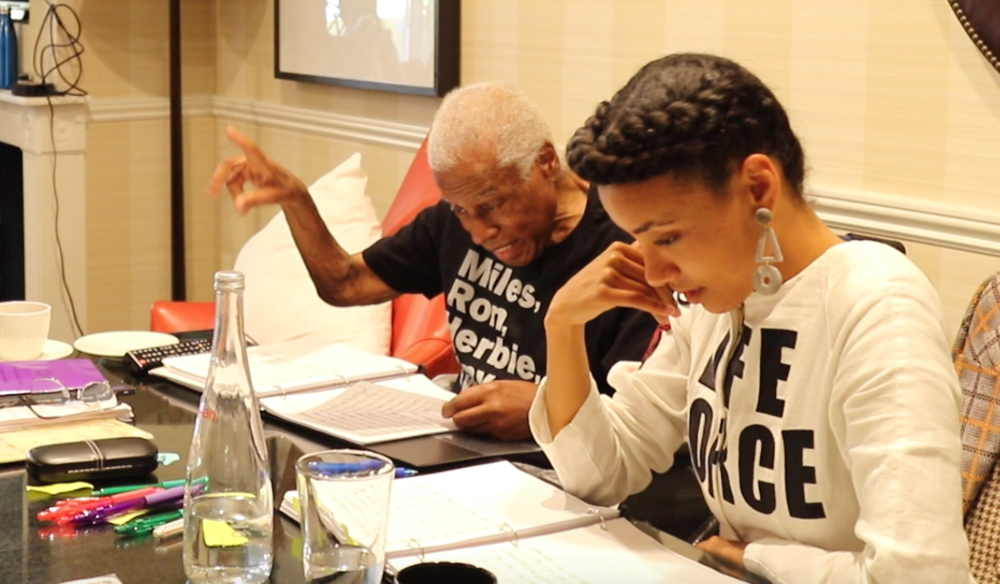

Shorter (left) and spalding (right) in rehearsal.

Photograph courtesy of Real Magic

Shorter’s score, written for a 28-piece chamber ensemble, is not designed to be jazz. spalding says he has never called the piece anything but opera—not even a “jazz opera.” The production’s conductor, Clark Rundell, has said that there’s an inescapable “Wayne-ness” to the orchestration—“a subtlety of meter, a complexity of syncopation, and the most unexpected flicks of harmonic beauty”—but that the sound isn’t confined to jazz. Musical dramaturg Phillip Golub ’16 said, “If people think the opera sounds like jazz, it’s just because all modern jazz sounds like Wayne.”

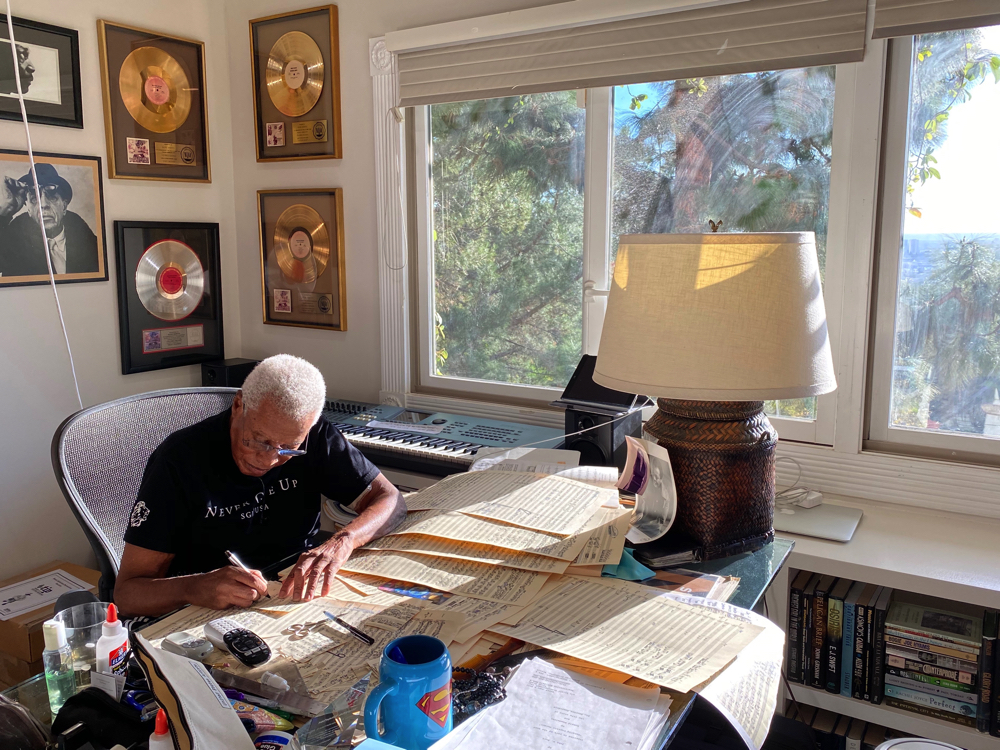

Shorter has dreamed of writing an opera since his teen years, but when his health began deteriorating a few years ago, the project became more urgent. spalding took a leave of absence from teaching at Harvard to move to Los Angeles, where she and Shorter worked together out of Gehry’s house (sometimes conducting rehearsals in his kitchen). Unlike most operas where the score is written after the libretto, spalding wrote the libretto to Shorter’s music. He was initially too ill to write by hand, but as the process continued, he regained enough strength to produce beautiful handwritten scores, sometimes waking at 3 a.m. to write. The sheet music was artwork all on its own, says Golub—full of Wite-Out, and new pieces of paper glued over old ones until it looked “almost like a Rauschenberg painting.” Shorter says that his goal throughout the composition process was to make “real magic, no gimmicks.”

Shorter, pictured here in his office, composed the entire score painstakingly by hand.

Photograph by Jeff Tang; courtesy of Real Magic

Some of this “real magic”—and the most obvious jazz element in the opera—is Shorter’s jazz trio (Danilo Pérez on piano, John Patitucci on bass, and Jeff “Tain” Watts on drums). The group plays onstage during acts two and three, with no musical notation to follow besides the “windows” Shorter wrote into the score, during which they’re invited to improvise. The “open tense” of spalding’s Iphigenia is improvisational as well, as she uses wordless vocal improvisation to break out of the myth, its notation, and its orchestration. In act three, the “open tense” takes over, to the extent that no one in the company on or off stage knows precisely what will happen. spalding did not write a pre-defined ending. “There was something about being a writer collaborating with a very important figure, where I was feeling this kind of creepy power of telling this story and getting to put my spin on it. That’s not inherently bad, but I just thought, wow, wouldn’t it be fun, when you finally have the baton, to be like, forget batons, you know?” she said in a panel discussion after the debut. She decided to “let go of the reins of the tyrannical storyteller,” and allow the ending to be “co-devised by the people who are actually in the room bringing the story through their bodies” in real time instead.

This meant that the company of opera singers had to musically improvise, not in an imitation of the African-American jazz aesthetic, but as themselves. The opera ends with the Greek soldiers improvising with one another and the jazz trio, singing “regular-degular,” as spalding called it. “After all that profound, high-level, athletic singing, it’s so impactful and there’s such intimacy just hearing these men search for sound together,” she said. “There’s no room for it to be performative because it’s improvisational.”

As the opera travels from its debut in Boston to the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.; Berkeley, California; and the Broad Stage in Santa Monica, the theme of re-writing and “open tense” will remain alive in the production process. Even just a few days before the opera’s first public performance, Shorter sent 21 new pages of music he hoped would “help the vocalists break out and create good trouble.” spalding said the work will continue to evolve, given its improvisational elements. And while the touring production might not be “jazz” per se, it will still embody Shorter’s definition of the genre: “I dare you.”