At twilight, the bulbous hoodoos and sculpted plateaus of the Sonoran Desert lose their depth, standing like cardboard cutouts against the dim blue sky. The illusion lasts only a few minutes, but that’s when photographer Stephen Strom ’62, Ph.D. ’64 is in his element behind the lens. “Your senses are highly elevated and your mind is quite active,” he says, “when the three-dimensional desert suddenly becomes a two-dimensional entity.”

Stephen Strom

Photograph by Stephen Strom

Before he knew it as a photographer, the 80-year-old Strom encountered the desert as an astronomer. Those two-dimensional moments fell on either side of his nights spent observing stars at Tucson’s Kitt Peak National Observatory, where he chaired the galactic and intergalactic program. Even as he built his adult life and career in the Southwest, the New York City native still hesitated before the desert’s endlessness and unpredictability. “I had to overcome fear of this rather strange environment with creatures far different from those that wandered my apartment in the Bronx.”

That apartment is where Strom first found photography. His father, a high school teacher, supplemented the family income by “photographing all the Baby Boom babies,” and converted a closet in their 500-square-foot apartment into his dark room. There, he introduced his son to photo development and processing, which the school-age Strom appreciated with the “level of interest you’d expect from a curious child,” and not much more than that. He was too busy thinking about stars.

He devoured the astronomy section of the Book of Knowledge (a children’s encyclopedia Strom says was “a multi-step down from the Encyclopedia Britannica”) and overran the family apartment with his scientific doodads, including, but not limited to: a chemistry kit, model train, ham radio, Galilean telescope, and of all things, a large beer barrel—whose curved edge he used to grind new telescope mirrors. “Nothing salacious,” he says.

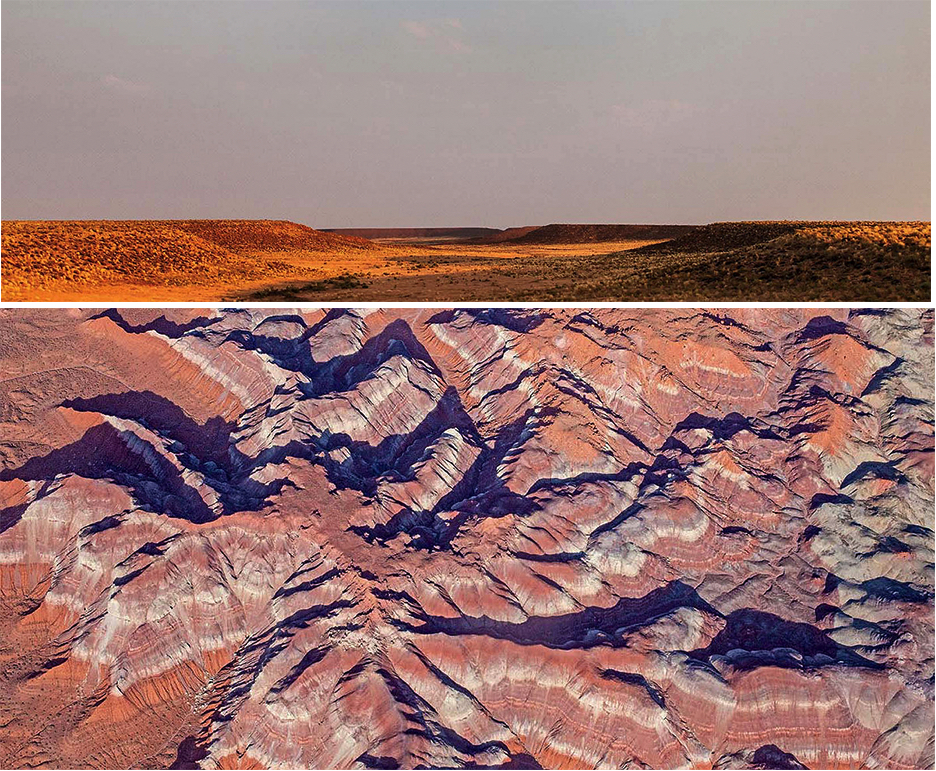

Top: Mesas at Lime Ridge, southwest of Bluff, Utah (2017); bottom: aerial view of badlands near Clay Hills, Utah (2016)

Strom earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees, and completed his Ph.D. in astronomy, at Harvard, where he worked as a lecturer before eventually moving to the Southwest to work at Kitt Peak. Photography was always part of his astronomy career, in a technical sense. He and his astronomer wife, Karen Strom ’64, used photographic plates to record light spectra and determine how galaxies were assembled. It wasn’t an artistic outlet for him until Strom’s youngest son enrolled in a photography course at the Tucson Museum of Art. He was a minor, so the art teacher said his parents had to come to class, too.

The course “ignited something” in Strom and his wife, and they enrolled in more classes and started photographing the desert landscapes near them, namely areas on the Navajo Reservation. “I know this sounds kind of trite, but we realized we’d been gathering photons from the landscape, treating the landscape as an object rather than the home of people,” he says. “We decided that we wanted to learn more about the people who lived there and maybe give something back.” The Stroms taught elementary-school math, as well as arithmetic courses for un- and underemployed Navajo adults—“not calculus, but stuff that’s actually useful to people.”

Strom met Creek poet Joy Harjo, the twenty-third poet laureate of the United States, while teaching. Harjo, with whom he collaborated on a joint photography/poetry book, Secrets from the Center of the World (1989), has written that Strom’s work captures the mysterious beauty of the landscape which the Navajo people call “the center of the world”: his “photographs lead you to that place. The camera eye becomes a space you can move through into the powerful landscape he photographs. The horizon may shift and change all around you, but underneath it is the heart with which we move.”

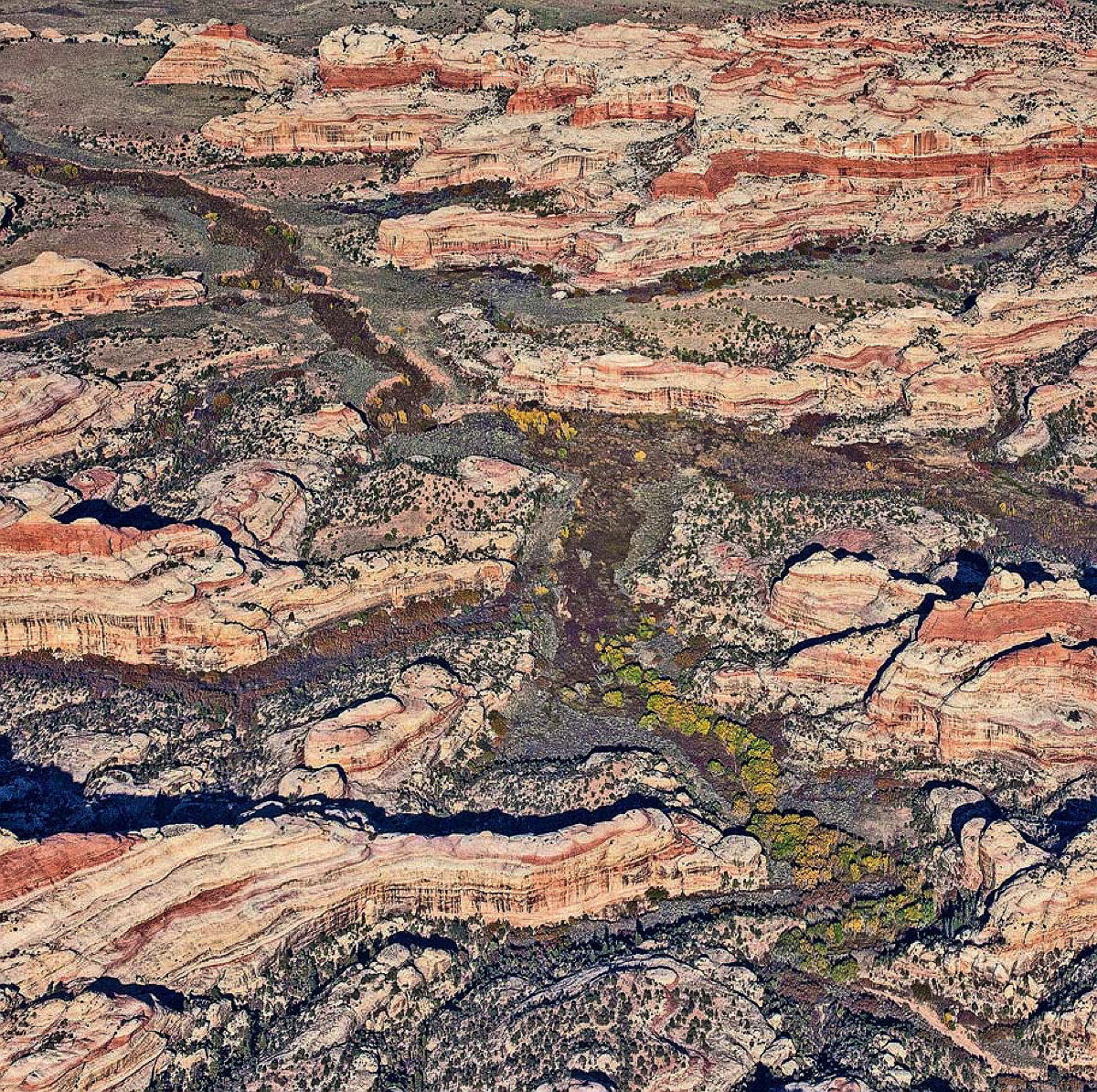

Aerial shot near Salt Creek Mesa (2015)

Photograph by Stephen Strom

He is not the desert photographer of citrus-colored sunsets bathing sandstone and saguaros in dramatic, saturated light. He says he tends toward “a rather pallid palette, instead. I like to think it’s understated.” His photographs—often captured in those two-dimensional moments or in the harsh, shadowless light of mid-day—lay bare the sculptural and chromatic rhythms of the desert, without any of the romantic accoutrements. Limiting the contrast reveals new forms in the landscape: in the aerial shot “Mudhills, Painted Valley,” 90-foot crevices flatten to resemble spindly poplar tree branches, and in “Abandoned Hogan south of Bluff, Utah,” a traditional Navajo dwelling is virtually indistinguishable from the roan-red, shadowless desert around it.

Both as a photographer and an astronomer, Strom finds patterns in places some find too vast and desolate to have coherence. “This is rather a pious hope,” he says, “but I hope that when viewers look at the way I’ve presented a landscape, they don’t walk away saying, ‘Wow.’ Instead, I hope they invest time in an image, and then the next time they go into that landscape, they’ll look at it in a far less casual way than they would have, had they seen it through another lens.”

His work has a call to action. Rather than focusing on gallery exhibitions, Strom collaborates with scientists, poets, and writers on books about land conservation and preservation. His recent book with writer Jonathan T. Bailey, The Greater San Rafael Swell: Honoring Tradition and Preserving Storied Lands, details how ranchers, miners, conservationists, and Native American tribal nations in Emery County, Utah, worked together to preserve public lands while supporting the land uses of people who have relied on it for generations. “Simply doing photography for aesthetic reasons and internal satisfaction just isn’t enough for me,” he says. He wants viewers to find his landscape beautiful, yes, but also to “wonder why mining the heck out of various parts of that landscape would be an offense to nature and the people inhabiting it.”

Even now at 80 years old, Strom returns to the desert again and again to photograph, sometimes lugging heavy equipment. “I wouldn’t exactly call me ripped, but I am motivated,” he says. He describes himself as very impatient (“I’ll dive into anything”), but it takes a patient, or at least a very persistent person, to spend hours hiking for just one shot, or to spend all night in an observatory to witness a single astronomical event. He is patient enough to have spent a life finding patterns, and patient enough to await a two-dimensional world, even if it’s there for only a few moments.