Before he became Charles III upon the death of his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, on September 8, he was the Prince of Wales. In that capacity, he was the outstanding presence at the University’s 350th anniversary blow-out in 1986. Funny, self-deprecating, and wise by turns, Prince Charles, those many years ago, showed all the attributes that have served him well during his long decades of devoted apprenticeship for his new royal role. Harvard Magazine’s November-December 1986 issue, devoted largely to covering the whole shebang, focused much of its attention on H.R.H., as he captured the crowd in Tercentenary Theatre from his first remarks:

As an old Cambridge man, and one hailing from a college not more than an easy bicycle ride from John Harvard’s Emmanuel College, I am particularly pleased and proud to be standing here ‘in the Yard.’…I must confess that I am somewhat surprised, as well…because I thought that in Massachusetts they weren’t too certain about the supposed benefits of royalty. Indeed, before coming here I noticed that at least one American newspaper had said it was a definite mistake to invite someone as appallingly undemocratic as The Prince of Wales. It just showed how out of touch Harvard was with the United States, it went on.

Lest his hearers get too full of themselves, he continued, “I confess that I have not addressed such a large gathering since I spoke to 40,000 Gujurati buffalo farmers in India in 1980, and that was a rare experience.” From there, the Prince turned serious—addressing matters of education, protection of the environment, and promotion of human wellbeing that have ranked high among his lifelong interests and concerns. “While we have been right to demand the kind of technical education relevant to the needs of the twentieth century,” he observed, “it would appear that we may have forgotten that when all is said and done, a good man, as the Greeks would say, is a nobler work than a good technologist. We should never lose sight of the fact that to avert disaster, we have not only to teach men to make things, but also to produce people who have complete moral control over the things they make.” He warned of the need for "moral and intellectual training if we are to escape from the leadership of clever and unscrupulous men.” Though not all his prescriptions may appeal today, at least in the form he spelled them out then (and some of the language seems dated in other ways, too), their underlying values and sentiments resonate still:

Surely it is important that in the headlong rush of mankind to conquer space, to compete with nature, to harness the fragile environment, we do not let our children slip away into a world dominated entirely by sophisticated technology, but rather teach them that to live in this world is no easy matter without standards to live by.

Among those challenges, he suggested, is determining how to “guard against bigotry, against the insufferable prejudice and suspicion of other men’s religions and beliefs, which have so often led to unspeakable horrors throughout human history, and which still do?” Institutions of higher learning, he concluded, had an essential role to play in resisting the “dark side” of human nature: “If they succeed in serving not just the immediate needs of the present but something greater than themselves yet to come, the chances are that they will not only renew themselves but help renew their ailing societies.”

We thank Lem Hewes, J.D. ’65, who attended the 350th and recalled the speech, for pointing us back to it, prompting this reprinting of the relevant text and accompanying images from the 1986 coverage. Thank you, again, Prince Charles. Long live the king. ~The Editors

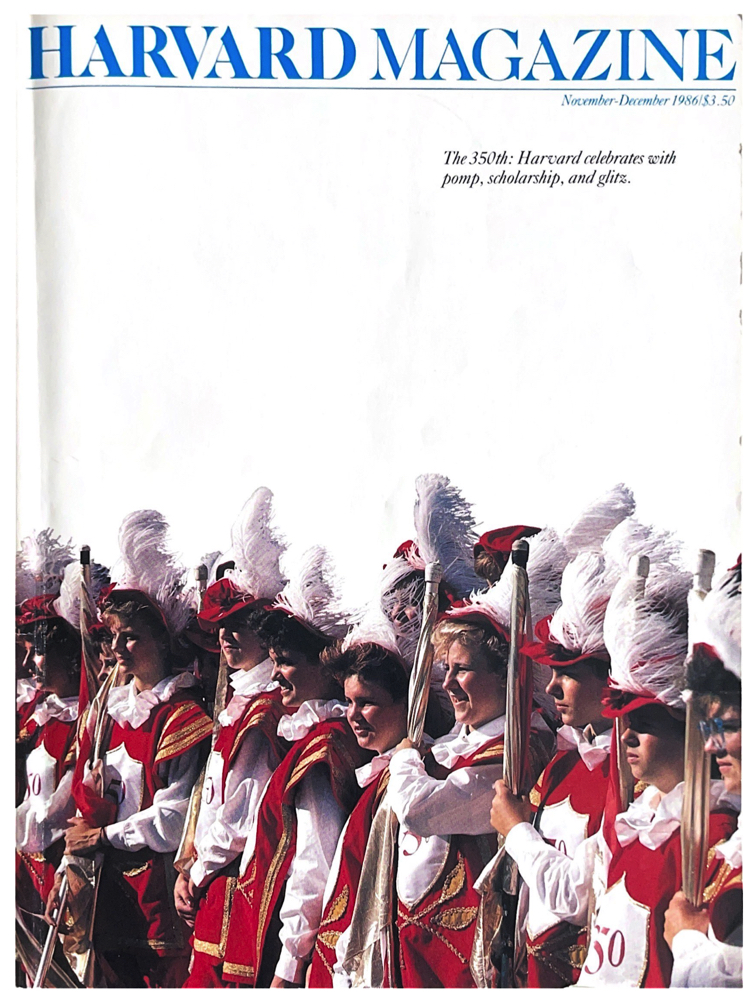

Mark Lennihan's cover photograph shows members of the Blessed Sacrament Color Guard of Cambridge and the St. Anthony's Color Guard of Everett, international champions in their métier, bringing 350th pageantry to Harvard Stadium.

VISITATION

Photograph by Mike Quan

The Prince of Wales brought glamour. George Shultz brought politics. Bonnie Raitt put song in our hearts. Tommy Walker sprayed us with stardust. Much else went on during Harvard's 350th. Covering so many simultaneous happenings was a reportorial challenge, surmounted only with the aid of loyal Ware Street Irregulars who volunteered their efforts to augment our staff's.….

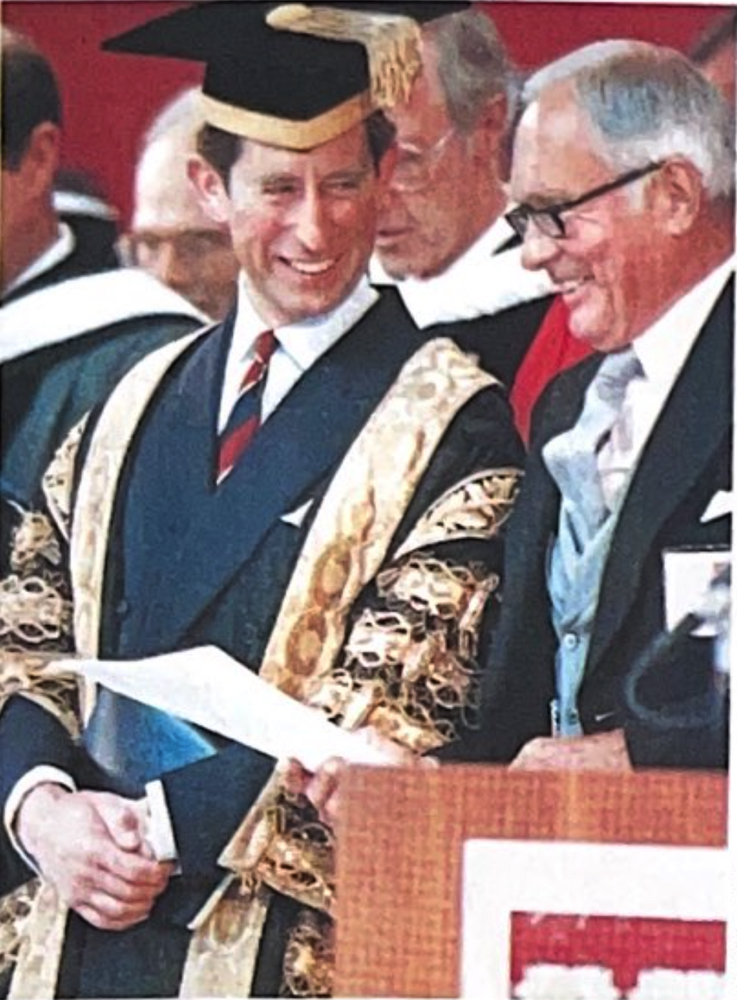

At right, above, is Francis H. Burr ’35, former Senior Fellow of Harvard College and chief marshal of the 350th. He led a 35-person committee that began making plans years ago. But then so did this magazine. Back in 1978 we consulted a classicist—Mason Hammond ’25, caller of academic processions at both the 1936 and 1986 observances—as to how to refer in Latin to a 350th anniversary. Professor Hammond advised against it, but allowed that the ancients might have sanctioned a sesquipedalian term that literally means “the seventh half-century anniversary.” It appears on the spine of this issue: Sollemnia Semisaecularia Septima.

Drawing by Dorothy Ahle in the Boston Globe.

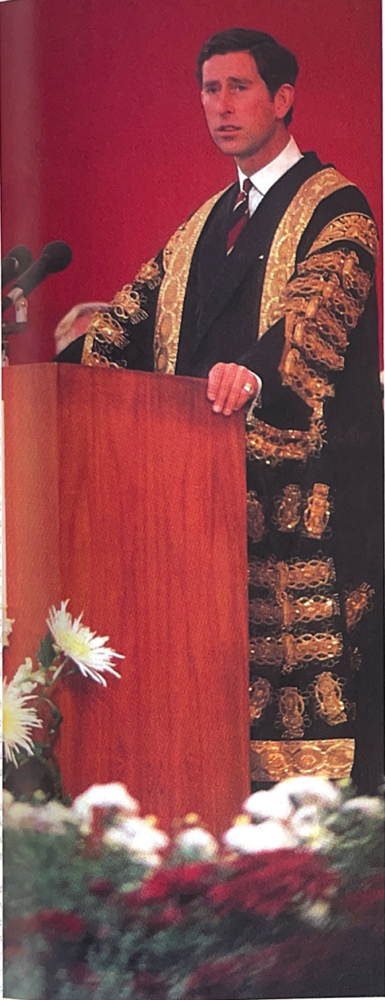

H.R.H.

His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales steals the show. Delivering the main address on Foundation Day, he speaks of the need for moral education. He wears the gown of the chancellor of the University of Wales, made of silk damask embroidered with gold lace in an acorn-and-oak-leaf design on the shoulders and with a Welsh dragon at the back.

[Francis H. Burr ’35, former Senior Fellow of Harvard College and chief marshal of the 350th] introduced the Prince of Wales. As His Royal Highness was waiting to enter Tercentenary Theatre that morning, he had, reportedly, a pronounced case of the jitters. But when he rose to speak, he seemed perfectly at ease. Perhaps he had divined that his audience wanted nothing from him that he couldn’t deliver amply.

“I can only say the suspense has been killing me,” the Prince began. “You have devised an exquisite torture for the uninitiated. But I realize now that all my character-building education, which I have endured in the past, has prepared me for this one great occasion.”

“He’s wonderful,” said a woman in the audience to her companion. “He has beautiful hands.” The Prince continued:

“As an old Cambridge man, and one hailing from a college not more than an easy bicycle ride from John Harvard’s Emmanuel College, I am particularly pleased and proud to be standing here ‘in the Yard.’…I must confess that I am somewhat surprised, as well…I am surprised because I thought that in Massachusetts they weren’t too certain about the supposed benefits of royalty. Indeed, before coming here I noticed that at least one American newspaper had said it was a definite mistake to invite someone as appallingly undemocratic as The Prince of Wales. It just showed how out of touch Harvard was with the United States, it went on. Have no fear, Ladies and Gentlemen, I am used to being regarded as an anachronism. In fact, I am coming round to think it is rather grand.…

“I have been overwhelmed by the honor you have done me in including me in your celebrations,” said the Prince. “I confess that I have not addressed such a large gathering since I spoke to 40,000 Gujarati buffalo farmers in India in 1980, and that was a rare experience.”

The heart of Prince Charles’s remarks concerned education— the sort that can produce the “balanced, tolerant, civilized citizens we all hope our children can become.” He said:

“I cannot help feeling that one of the problems gradually dawning on the Western, Christian world is that we have for too long, and too dangerously, ignored and rejected the best and most fundamental traditions of our Greek, Roman, and Jewish inheritance. I would suggest that we have been gradually losing sight of the Greek philosophers’ ideal, which was to produce a balance between the several subjects that catered for a boy’s moral, intellectual, emotional, and physical needs. While we have been right to demand the kind of technical education relevant to the needs of the twentieth century, it would appear that we may have forgotten that when all is said and done, a good man, as the Greeks would say, is a nobler work than a good technologist. We should never lose sight of the fact that to avert disaster, we have not only to teach men to make things, but also to produce people who have complete moral control over the things they make. Never has this been more essential and urgent than at this moment in man’s development. Never has it been more important to recognize the imbalance that has seeped into our lives and deprived us of a sense of meaning because the emphasis has been too one-sided and has concentrated on the development of the intellect to the detriment of the spirit.…

The faculty exits Tercentenary Theatre and mounts the steps of Widener Library set lavishly with crimson and white chrysanthemums. Most marchers descend at once at the sides and join the multitude. Others enter to lunch with Prince Charles in the Widener Reading Room.

Photograph by Mark Lennihan

Table for one. At a crowded Yard spread, a guest finds an empty place to put her plate. The Rolls belongs to the caterer.

Photograph by Mark Lennihan

“All the best thought in Greece, Rome, and Judea emphasized the interdependence of moral and intellectual training if we are to escape from the leadership of clever and unscrupulous men. There is no doubt in my mind that the education of the whole man needs to be based on a sure foundation—in other words, on the values of our own Christian, Western traditions, which in turn are the product of Hellenism and Judaism. That of course does not mean we have to deny the validity of other men’s traditions. We should indeed look for those elements that unite us rather than concentrate on the things that make us different. What I am trying to say is that if during the course of a person’s education he is introduced to the principles of a religious attitude to life, as the Greek philosophers and Hebrew teachers would have seen it, then it is perhaps possible to learn to equate human rights with human obligations. It is possible then to see a relationship between moral values and the uses of science, and for those who affect our lives in some way or other through planning and administrative committees to appreciate that at the end of the process there is always a man or a woman, or a family. Surely it is important that in the headlong rush of mankind to conquer space, to compete with nature, to harness the fragile environment, we do not let our children slip away into a world dominated entirely by sophisticated technology, but rather teach them that to live in this world is no easy matter without standards to live by.

After lunch the Prince attends a symposium on the future of the city and meets with students for tea and talk, above.

Photograph by John Nordell

Top right: Supreme Court Justice Harry A. Blackmun '29, L.L.B. '32, attends a symposium on the Constitution. Bottom right: Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger '38, J.D. '41, at a symposium on avoiding nuclear war, is handed a note and rises to say that a hostage crisis in Pakistan is over. Left: Sheik Ahmed Zaki Yamani, LL.M. '56, petroleum minister of Saudi Arabia, and banker David Rockefeller '36, at Foundation Day exercises. Yamani spoke at a symposium on the world oil market.

Photographs by Jim Harrison

"And yet, at the same time, how do we guard against bigotry, against the insufferable prejudice and suspicion of other men’s religions and beliefs, which have so often led to unspeakable horrors throughout human history, and which still do? How do we teach people to recognize that there is a dark side too to man’s psyche and that its destructive power is immense if we are not aware of it? This, of course, is the universal dilemma, but I would venture to suggest that an instrument has been lying within our reach for nearly a hundred years and is still not used enough. There is in existence a proved and tested natural science dedicated to the study of the soul of man and the meaning of his creation. As in the past religious teaching was an essential part of the curriculum, perhaps there is now a need in universities for some introduction to the natural science of psychology? We are, to all intents and purposes, embarked on a perilous journey. The potential destruction of our natural earth; the defoliation of the great rain forests (with all the untold consequences of such a disaster); the exploration of space; greater power than we have ever had or our nature can perhaps handle—all confront us for what could be a final settlement. But if we could start again to reeducate ourselves, the result need not be so frightening. Over Apollo’s great temple was the sign ‘Man know thyself.’ This natural science of psychology could perhaps help to lead us to a greater knowledge of ourselves, knowledge enough to teach us the dangers of the power we have acquired and the responsibilities as well as the opportunities that it gives us. Could man, at last, begin to learn to know himself? Could we expect institutions of higher learning to become once again keepers of knowledge that is not mere knowledge and facts but, as the Greeks called it, ‘Metanoia’—knowledge that transforms? Could they reexplore that religious dimension primitive people called the great hunger, the overwhelming and inexplicable impulse that brought man out of the remote and dangerous past to where he is today through passions of the spirit? It was a hunger that was to provide a sense of meaning and the life of meaning that conducted him in the search for truth in all dimensions—material, physical, and spiritual. Thus, however well these institutions may serve an existing social order, if their vision of themselves ends there they will diminish and perish. If they succeed in serving not just the immediate needs of the present but something greater than themselves yet to come, the chances are they will not only renew themselves but help to renew their ailing societies.”