It looks like something out of a science fiction novel. Architect Étienne-Louis Boullée’s 1784 drawing, “Cénotaphe de Newton,” which imagines Isaac Newton’s fantastical final resting place, is the first piece visitors see when they enter Dare to Know, Harvard Art Museums’ new installation of prints and drawings from the Enlightenment era. The cenotaphe is as imaginative as it is slightly unsettling: a great sphere (planned to be taller than the Great Pyramid of Giza) features terraces around its circumference like the rings of Saturn, and a seemingly inaccessible second-story entrance. Out-of-this-world and physically improbable, it looks more like a design sketch for the Death Star in Star Wars than an architectural drawing from an era deemed the “age of reason.”

That’s part of the point. “We wanted to shake up our visitors at the start and get them to start questioning what they think they know about the Enlightenment,” says Weyerhaeuser curator of prints Elizabeth Rudy. The exhibit brings together 150 prints, books, and drawings from Harvard and collections around the world, including the National Gallery of Art and the Musée du Louvre.

Ideas may have been the engine of the Enlightenment, but paper was the fuel, says co-curator Kristel Smentek, an associate professor of art history at MIT. “Prints and drawings are constitutive of the Enlightenment’s debates and of its mixed legacies. They allowed for inventiveness in subject matter, and because works on paper are very mobile, they could be dispersed to a wide audience.” The period was “awash in paper,” according to Rudy. It was the medium of everyday life—as displayed in the exhibit with a shadowbox of common miscellanea like lottery tickets, ball invitations, and paper money—and the medium of intellectual exchange.

Drawings and books during the Enlightenment made both new and familiar things visible, according to the curators. William Hamilton, British diplomat to the Court of Naples, visited Mount Vesuvius countless times to create a richly illustrated book to show uninitiated audiences what volcanos looked like and how they worked. Another illustrated book, Religious Ceremonies and Customs of All the Peoples of the World, attempted to investigate and detail global religious customs.

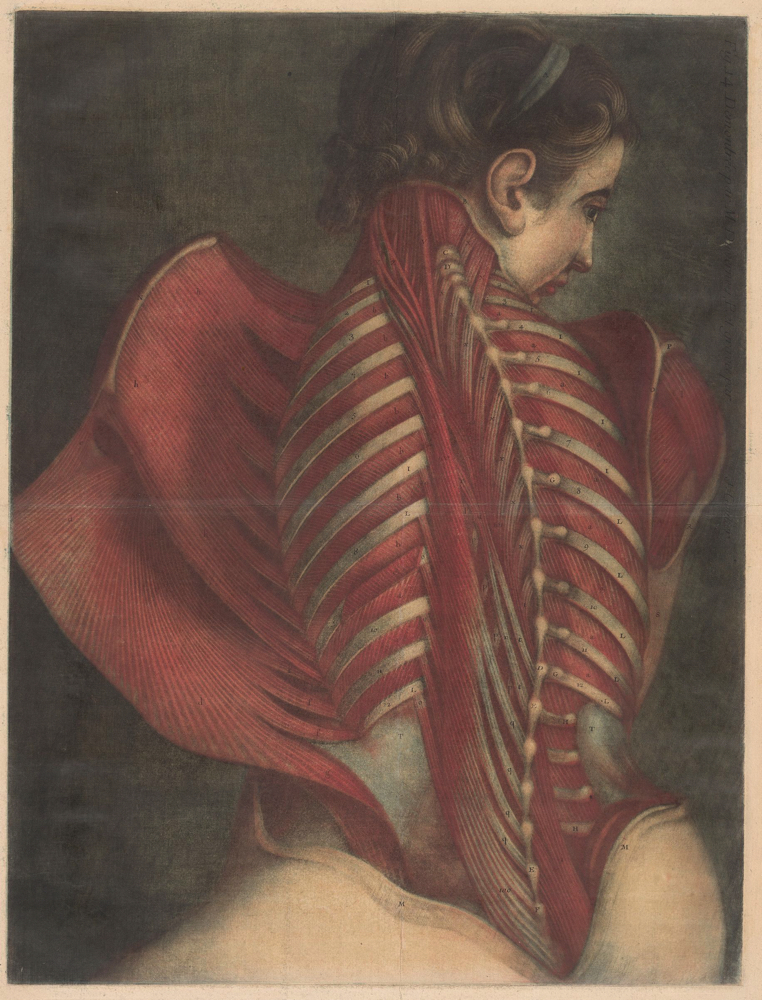

Jacques-Fabien Gautier d’Agoty (French, 1710–1781), "Muscles of the Back," Plate 14 from Myologie complette en couleur et grandeur naturelle (Complete Scientific Study of Muscles in Color and Life-Size), by Joseph Guichard Duverney (Paris: Gautier, 1746). Color mezzotint. Sheet: 76 × 53 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the SmithKline Beckman Corporation Fund, 1968, 1968-25-79n, TL42415.2.

Image: Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Photo: Joseph Hu.

Other drawings on display focus on human anatomy, but like many objects in the exhibit, “They’re not always what they immediately appear,” says Rudy. Jacques-Fabien Gautier d’Agoty’s “Muscles of the Back,” at first appears to be only a striking anatomical print of a woman’s back, dissected to reveal her ribcage and muscles. But it’s as much fantasy as it is science, her muscles unfolding like wings about to take flight. Rudy says, “Many Enlightenment drawings were investigative, but they were also meant to provoke your imagination.”

“There’s not one Enlightenment, but many,” she continues. “It was a very complicated time where things were constantly evolving, because thought was constantly changing. You can see that in these sources.” The exhibit features two strikingly similar broadsides with diagrams of slave ships. One, produced in 1770, portrays the Marie Séraphique, which sailed from the large slave-trading port of Nantes and celebrates the ship’s large carrying capacity for “human cargo.”

The other broadside, produced just 20 years later, uses a similar diagram of a slave ship to enumerate the many atrocities being inflicted on enslaved individuals. It was one of the most influential anti-slavery prints of the eighteenth century. “Virtually the same image is being used to opposite ends,” Rudy says. “They’re both using the graphic arts to persuade people to think differently.” Although many people think of the Enlightenment as a period characterized by cool rationality and scientific investigation, the works it produced were not necessarily objective. According to Smentek, “Prints and drawings were actually active agents in the thinking of the time and not passive documents of what was happening at the time. Often, they were used to persuade.”

Those appeals could be emotional ones. “The Enlightenment is often understood as ‘the age of reason,’ but one can equally well make the argument for it as ‘the age of feeling,’” she says. Printed materials like the abolitionist broadside made appeals to empathy: “This speaks to the real emphasis in the eighteenth century on the moral and social value of humans’ inherent capacity to identify or empathize with other human beings.” She adds, “Those emotional appeals were mobilizing a shared human emotion as a catalyst for change.”

The final room in the exhibition centers on the imagination that characterized the Enlightenment, highlighting pieces like Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle’s 12-foot-long watercolor, Figures Walking in a Parkland (c. 1783-1800). The countryside landscape was painted on conjoined sheets of translucent paper and wound around rollers in a backlit box—producing an early form of moving images. Other pieces, like Augustin Pajou’s Diamedes Attacked by the Trojans (1756), playfully reimagine classical forms or architecture of ancient Rome and Greece. The curators say perhaps this focus on ancient empires was a way of making sense of the political upheavals that rocked the Enlightenment era: the French, American, and Haitian revolutions. “These recent events were violent, and they transformed social-political order. There was anxiety about the latent irrationality within the rational human being,” Smentek says. “There was an unease underlying this study of fallen civilizations, realizing that civilizations fall, and they may not come back.”

The exhibition ends with artworks from revolutions now viewed as the culmination of Enlightenment ideals. “All the artwork was made when these moments of revolution were provisional—when they were still ongoing,” Smentek says. Given paper’s relative ease of circulation, the drawings capture differing attitudes about the revolutions at critical moments in time.

The curators hope visitors find connections between the problems Enlightenment thinkers wrestled with, and those prevalent today. “For example, using the same image to tell two different stories is still very much a modern-day issue. Turn on CNN versus Fox and they’ll use the same image to tell you two completely different stories,” says Heather Linton, curatorial assistant for special exhibitions and publications. “With all the pieces in this exhibit, the problems then may not be identical, but the issues still persist today.”

Dare to Know runs until January 15 at the Harvard Art Museums. An illustrated catalogue with 26 thematic essays—an A-to-Z exploration of the Enlightenment, written by leading scholars—accompanies the exhibition.