The matchup this Sunday between the Harvard and Howard men’s basketball teams may seem routine—the two schools have been meeting on the court for almost a decade—but the opportunity to play the game might not exist if not for an early-twentieth century Harvard student and Howard alumnus named Edwin Bancroft Henderson. Known as “the Grandfather of Black Basketball,” Henderson learned the sport at a Harvard summer session, formed Howard’s inaugural varsity squad during the 1910-11 seasons, and was the first person to introduce the game to black players on a wide-scale, organized basis.

For Henderson, who was posthumously inducted in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, it was all part of a broader career that included teaching, coaching, activism, and writing.

Henderson was born in 1883 in a small house in a Washington, D.C., alley. He shone as a student in the city’s segregated public schools and in 1902 graduated with honors from the high-achieving M Street School, where he played football and baseball. Two years later, he graduated first in his class from Minor Normal School, a teaching college in the district. Afterward, he’d planned to teach elementary school, but Anita Turner, a physical training instructor in the city’s segregated public schools, encouraged him to attend Harvard’s Summer School of Physical Education. The program was led by Dudley Allen Sargent, assistant professor of physical training and director of Hemenway Gymnasium, and Turner had been one of the first black women among its graduates. Henderson borrowed money for carfare, tuition, and lodging and waited tables at a boarding house for meals.

At Harvard, he studied innovative approaches to physical education and chatted with professors like psychologist William James and philosopher Josiah Royce when they exercised at Hemenway. There were painful experiences too: Henderson was one of only two African Americans in his class of 114, and in a later interview, he recalled going to a local barbershop and requesting a trim, but the white barber instead shaved off a strip of hair, from the back of his head to the front, and laughed. Henderson did not return to a barbershop operated by whites for decades.

While he was in Cambridge, Henderson also learned to play basketball, a game that at that time was only two decades old. When he returned home from his first summer at Harvard (he went back to the program in 1905 and 1907), he began teaching physical education to black students in Washington schools. His curriculum included basketball. The students at first saw it as a “‘sissy’ game,” Henderson later wrote, especially compared to the “rugged” (and also new) sport of football; but basketball grew more popular after he organized exhibition contests through the Inter-Scholastic Athletic Association of Middle Atlantic States (ISAA), an all-black amateur sports conference he had helped establish. In 1908, the ISAA created a basketball league featuring squads from local schools and athletic clubs. Henderson was the instructor and administrator for the league, which played games on Saturday nights, charged 25 cents for admission, and featured performances from a local orchestra.

Henderson himself was an elite basketball player. Beginning in 1909, he was the center on a team featuring the best black players in Washington. During his squad’s first contest, a matchup with a New York City club, Henderson missed three first-half free throws but made what the New York Age described as “four pretty goals” in the second half to secure a win. His team, which included numerous Howard students and was affiliated with the Twelfth Street Colored YMCA, went undefeated during the 1909-1910 season, giving them the unofficial title of Colored Basketball World Champions. Henderson played his final game on December 26, 2010 (a victory for the Twelfth Streeters in New York): his wife, Mary Ellen, whom he’d married two days earlier, felt the sport was dangerous. Afterward, Henderson arranged for the Twelfth Streeters to become Howard’s first varsity basketball team, and during the 1910-1911 season, he coached them to another undefeated, world championship campaign.

Henderson and his wife moved to Falls Church, Virginia, in 1910, where he got involved in civil rights activism. In 1915, after the Town Council approved an ordinance restricting black residents to a small area—which would have forced two-thirds of the town’s African American population to sell their homes and move—Henderson organized the Colored Citizens Protective League. The group filed a lawsuit to block enforcement of the ordinance and fought the case all the way to the Virginia supreme court; in 1917, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Buchanan vs. Warley outlawed forced housing segregation. Less than a year later, in June 1918, Henderson formed the first rural branch of the NAACP in Falls Church. He received threats from the Ku Klux Klan during these years, incluing a letter threatening to tie him to a tree and whip him. He kept his phone number unlisted for 50 years.

Harvard’s Stemberg Coach Tommy Amaker began scheduling a regular matchup with Howard in 2013 to celebrate the schools’ connections and shared tradition of excellence (Howard is often referred to as the “Harvard of the HBCUs”). For him, contests with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) carry extra significance. After last year’s game against Howard, a 77-69 Crimson win, the coach pointed out that there was a time when, for black Americans pursuing higher education, HBCUs were really the only option. Adding HBCUs to Harvard’s schedule (the Crimson have played Howard six times since 2013 and opened the last two seasons against Morehouse) fosters unity, Amaker believes.

Tommy Amaker (with his back to the camera) greets Howard head coach Kenneth Blakeney at the start of last year's game.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletics

The connection runs even deeper than that, though. Amaker grew up in Falls Church, and his mother, Alma Amaker, was once a student of Henderson’s wife there. Mary Ellen Henderson, an educator like her husband, taught in Falls Church’s black schools; she also advocated for better facilities for African American students, including a new elementary school, which opened in 1948. One of its early students was Alma Amaker, then a fourth-grader. She later told the Falls Church News Press that the water fountains at the new school (an upgrade from the dipper and water bucket more common in black classrooms at the time) were the first ones she’d ever seen without a sign that read, “For Whites Only.” Alma Amaker became a longtime educator herself in the Fairfax County Public Schools, and she spoke of Mary Ellen Henderson as a teacher and mentor. Decades later, Tommy Amaker said he went into coaching and teaching in part because of his mother’s example.

Harvard foward Josh Hemmings goes up against two Bison defenders in Lavietes Pavilion.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletics

Despite living in Falls Church, Edwin Henderson continued to play an influential role in Washington. He took the colored streetcar into the city to work in the district’s segregated schools, where he became director of physical education, safety, and athletics; among his students over the years were jazz great Duke Ellington and Charles Drew, a pioneer in developing blood banks. Henderson earned a bachelor’s degree from Howard in 1930 and a master’s in 1934 from Columbia University’s Teacher’s College. He successfully fought discriminatory practices in numerous local institutions, including Uline Arena and Constitution Hall.

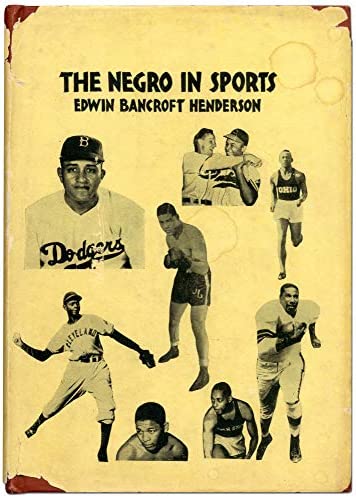

After retiring in 1954, he remained a powerful advocate for racial equality, writing thousands of letters to the editor to local newspapers in Virginia and Washington; his myriad articles and books include The Negro in Sports (1939), the first survey of the black experience in athletics. In 1974, Henderson was inducted into the inaugural class of the National Black Sports Hall of Fame, along with Muhammad Ali, Jesse Owens, and Willie Mays.

Henderson died in 1977, and in 2013 he was inducted into the Naismith Hall of Fame, recognition that came after a campaign led by Henderson’s family. The effort—which included letters of support from broadcaster James Brown ’73 and Fletcher University Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr.—also contributed to Henderson’s nickname: the “grandfather of black basketball.” Henderson’s grandson, Edwin Bancroft Henderson II, an historian and educator who is writing a book about his grandfather, explains that the moniker “father of black basketball” already belonged to John McLendon (an innovative coach who broke down racial barriers) and Robert Douglas (owner and coach of the New York Renaissance, a dominant black team). Because Henderson preceded them, he became the “grandfather of black basketball.”

To author Claude Johnson, whose book The Black Fives: The Epic Story of Basketball’s Forgotten Era chronicles early black basketball history, Henderson’s induction is significant in part because of his role introducing the sport to black players. “Without him,” Johnson told the Washington City Paper in 2008, “who knows if it ever would have been embraced as it was.” Remembering Henderson’s story, Johnson believes, is integral to the stewardship of the game. He likens it to tending to an ever-expanding “quilt of basketball.” “We’re all part of this quilt,” Johnson says, “Everybody has to take care of this game.”

On Sunday, Harvard and Howard will add another stitch.