The Connecticut capital is often seen as a bland, bypassable insurance industry hub, a messy tangle of highways endured en route to the real city of New York. But Hartford, a seat of history, arts, and culture, has a beating heart of its own.

Marking Wallace Stevens's poetic commutePhotograph courtesy of the Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens

That Wallace Stevens, A.B. 1901, among the most inventive poets of the twentieth century, lived there, composing lines while strolling from his home to his downtown office at the Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co, speaks to the city’s duality and creative undercurrents. The Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens, a group of local enthusiasts, helps keep that spirit alive. Stevens was a devout walker who never learned to drive, notes the organization’s president Dennis Barone, professor emeritus in English at the University of Saint Joseph. Working as a young lawyer in Manhattan, Stevens would amble “to New Jersey and into the hills of Ramapo,” Barone says, and later in life easily made the daily 2.4-mile route through Hartford, passing historic Elizabeth Park, referenced in several poems. Visitors on a weekend visit to Hartford can follow in the poet’s footsteps, commemorated by the Friends as The Wallace Stevens Walk, through a trail of granite markers, each inscribed with a verse from his poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.”

The city’s literary legacy dates back further, to the birth in 1758 of Noah Webster, creator of the American dictionary. Nineteenth-century authors (and neighbors) Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe also lived there, in the artistic enclave known as Nook Farm. The homes of each of these notables are now museums and educational centers open to the public.

Noah Websters's birthplacePhotograph courtesy of the Noah Webster House

The Noah Webster House, owned by the West Hartford Historical Society, was on a farm in what was a division of Hartford. Tour the restored period-furnished rooms, with samples of a lexicographer’s tools (quills and parchment), editions of early dictionaries, and artifacts like the gold ring holding hair from Webster and his beloved wife, Rebecca. Texts and a video describe his prodigious life, training as a lawyer but working as a teacher, fighting for education reform and standard literacy at a time when most children were packed into rooms with no books and ineffective instructors. Pro-independence, he championed the burgeoning American dialect and in 1783 wrote A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, a primary textbook used for more than a century. In 1828, he published the first comprehensive American dictionary, citing 70,000 painstakingly researched words. A Federalist leader, Webster also helped shape American copyright and intellectual property laws, fought against slavery, and cofounded Amherst College.

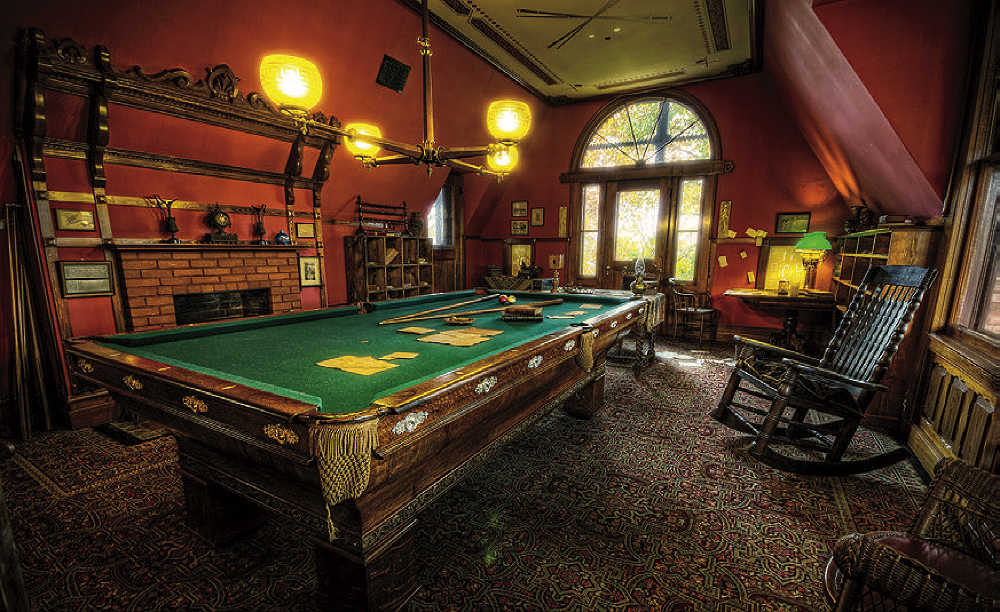

The Victorian Gothic Revival home of American writer Mark Twain (top) and his study-cum-billiards roomPhotographs courtesy of the Mark Twain House

Hartford was the first place that Mark Twain (locally known by his real name Sam Clemens) called a home. Attracted by the existing cluster of publishers, writers, and artists, Twain and his wife built an opulent house and settled in with their three daughters in 1871. There, his Missouri roots and Mississippi River explorations became fodder for narratives and humorous critiques that introduced characters such as Huckleberry Finn, Jim, and Tom Sawyer. The best part of the Mark Twain House & Museum tour is the writer’s top-floor sanctuary where he wrote, pondered, conducted business, and socialized over billiards. “Twain never tired of the game,” his biographer Albert Bigelow Paine wrote. “He could stay until the last man gave out from sheer weariness, then he would go on knocking the balls about alone.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe—writer, abolitionist, mother, and family breadwinner—was already famous for writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin (while living in Brunswick, Maine) when in 1873 she and her husband moved into the cottage-style house next door. It’s now called the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, offering tours, lectures, salons, and a research library. Guides highlight her life and work: “She was messy,” allows director of collections and research Elizabeth G. Burgess, writing in nest-like spots all over the house amid piles of papers and books. But tours also foster questions and open dialogue about the impact and legacy of the sentimental novel, an immediate sensation when first published as a 40-week serial in the abolitionist periodical The National Era. Starting in the foyer, guides point out diverse takes on the text (from James Baldwin and Laura Bush to Stowe herself). Moving into the Stowes’ sitting room, visitors can pore over copies of primary sources that gave rise to the book, among them the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and accounts of former slaves like Rev. Josiah Henson, upon whom Stowe modeled her fictional Uncle Tom. “We want people to look directly at the words that inspired Harriet,” Burgess says. “There is no way she could have done what she did without having read about the lived experience of courageous formerly enslaved people.”

Among those who spoke out, of course, was Frederick Douglass, who first visited Hartford, giving an anti-slavery speech on the grounds of First Congregational Church in 1843. I Am Seen…Therefore, I Am: Isaac Julien and Frederick Douglass (through September 24), at the downtown Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art,commemorates that trip and the activist’s contemporary influence. The film installation Lessons of the Hour is paired with nineteenth-century studio portraits of African Americans, reflecting the popularity of Douglass’s own image in his day and his insight about the new medium’s pivotal role in furthering emancipation. (The exhibit was curated by Harvard’s Fletcher University Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. and associate professor of history of art and architecture and African and African American studies Sarah Lewis.)

The Atheneum opened the year after Douglass came and is the oldest continually operating public art museum in the United States. It has a large permanent collection, notably of Hudson River School works and of early American furniture and offers year-round rotating exhibits and events for a diverse audience. Art shows this season also include Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures (through September 10), a series of photographs taken during road trips around the United States between 1997 and 2002, and Lisa Alvarado / MATRIX 192 (through September 3), featuring the Chicago-based artist’s floor sculptures and new paintings evoking Mesoamerican weavings with a psychedelic edge.

Bike, play, or lounge along Hartford’s revitalized riverfront, where festivals are held throughout the summer.Photograph by Sean Pavone/Alamy Stock Photo

From the museum, it’s a quick walk to the refurbished stretch of the Connecticut River waterfront. A 1.7-mile recreational path runs along the shore, linking Riverside Park to Mortensen Riverfront Plaza, with access to the 16.6-mile Charter Oak Greenway. The plaza is a hub of summertime events, from the Riverfront Food Truck Festival (July 20-23) to Shakespeare in the Park, presenting A Midsummer Night’s Dream (beginning August 11). The Riverfront Dragon Boat and Asian Festival (August 19) celebrates Asian and Pacific Islands culture through boat races, traditional dance and art, and martial arts demonstrations.

Robust gardens at Elizabeth ParkPhotograph courtesy of Elizabeth Park

For a quieter outing in nature, head to historic Elizabeth Park, where “there’s always something blooming,” notes Ann Drinan, director of office operations for the Elizabeth Park Conservancy, which cares for this 100-acre haven of botanical pleasures. Although the heritage roses peak in early June, the main rose garden flowers throughout the summer. Robust formal perennial and annual gardens are dazzling, or take the walking trails through the rock garden, meadows, woodlands, and along the pond. The land had been the estate and working farm of Elizabeth and Charles M. Pond, a wealthy industrialist who bequeathed the property to the city, which opened the park in 1897. Although the father of American landscape architecture, Frederick Law Olmsted, was born, raised, and buried in Hartford—and designed the picturesque Walnut Hill Park in the nearby city of New Britain—the Elizabeth Park master plan was conceived by Theodore Wirth. His rose garden opened in 1904, with 116 beds, drawing more than 200,000 people a year. Look also for the iconic weeping blue atlas cedar and the romantic stone bridge under the shade of old trees. The “Rhodie Walk,” along a swath of old-growth hardy New England favorites, runs partway around the pond and up to Prospect Avenue, where the “Sunrise Overlook” offers one of Hartford’s highest viewpoints. The park’s jazzy Pond House Café offers fine dining, and the Conservancy hosts events and outdoor concerts like those by the Bales-Gitlin Band (July 19) and Brazilian jazz vocalist Debóra Watts (August 9).

Stevens, often considered a poet of place, reveals a bond with the local landscape through verse. “Vacancy in the Park,” “Of Hartford in the Purple Light,” and “The Plain Sense of Things” suggest that whatever he noticed while meandering served his creativity. When asked to characterize the writer’s view of his adopted city, Dennis Barone offers part of “Connecticut Composed,” an essay Stevens wrote for Voice of America during the last year of his life: “The man who loves New England and particularly the spare region of Connecticut loves it precisely because of the spare colors, the thin lights, the delicacy and slightness of the beauty of the place. The dry grass on the thin surface would soon change to a lime-like green and later to an emerald brilliant in a sunlight never too full. When the spring was at its height, we should have a water-color, not an oil, and we should all feel that we had had a hand in the painting of it, if only in choosing to live there where it existed.”