Why Flying Is Miserable: And How to Fix It, by Ganesh Sitaraman ’04, J.D. ’08 (Columbia, $17 paper). High fares, reduced service to small cities, and rotten consumer experiences are a choice, not an inevitability, writes the Vanderbilt law professor. He declares the deregulation adopted in 1978 a failure; after $50 billion in public support during the pandemic, “[W]e now have fewer flights to fewer places at higher prices” and with overworked airline employees. Time to “choose to fix flying,” via renewed regulatory oversight of the industry, like a utility, he argues—or other, more sweeping measures.

Move Fast and Fix Things, by Frances Frei, UPS Foundation professor of service management, and Anne Morriss, M.B.A. ’04 (Harvard Business Review Press, $30). The authors have, like the rest of us, tired of the “move fast and break things” mantra that now has broken, perhaps, too many things. Leadership, they reasonably say, “is the practice of imperfect humans leading imperfect humans”—resulting in organizations in need of improvement. They thus aim at the hard work of making things better, “a deeply optimistic pursuit.” Though “impatient about progress,” they are clear-eyed about how that differs from tossing bombs and reveling in the wreckage (of the sort Frei saw firsthand during her turn as an Uber executive).

Learning to Imagine: The Science of Discovering New Possibilities, by Andrew Shtulman, Ph.D. ’06 (Harvard, $35). “The idea that children are imaginative but adults are not is a common theme in popular fiction,” observes the author, a professor of psychology at Occidental, citing The Little Prince and Peter Pan. He upsets that apple cart, noting that children “are most curious about things they largely understand”: confirming expectations, not challenging them. His clear, vivid exploration of his subject and how it works may cheer up adults, gladdened to learn the ways imagination “can be expanded through education and reflection.”

American Purgatory: Prison Imperialism and the Rise of Mass Incarceration, by Benjamin D. Weber, Ph.D. ’17 (New Press, $28.99). An assistant professor at the University of California, Davis, delivers an impassioned, at times furious, history-cum-advocacy account of the intersection of race, imperial reach (into the Philippines, and elsewhere), and the idea of penal colonies—all as prologue to contemporary U.S. imprisonment practices. James Monroe’s correspondence with Thomas Jefferson about finding a place to transport prisoners guilty of sedition or insurrection, prompted by a planned revolt of enslaved people in Virginia, is a sobering starting point for his inquiries.

The Entanglement, by Alva Noë, Ph.D. ’95 (Princeton, $27.95). A professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, challenges the notion that human beings and their culture are artifacts of “habit, custom, technology, and biology.” All are necessary, of course, but he maintains that “life and art are entangled” and always have been: witness Paleolithic cave paintings. In this sense, “Art makes life anew. We become something different in an art world. And crucially, our world has always been an art world.” Hence his title and his exploration of “how art and philosophy make us what we are” (the subtitle).

Rhetoric and Reality on the U.S.-Mexico Border, by K. Jill Fleuriet ’94 (Plagrave Macmillian, $29.99 paper). A University of Texas at San Antonio anthropologist and vice provost analyzes media depictions of the Rio Grande Valley “as a singular place of difference and threat” plagued by “failures of…health care, economy, and immigration”: the dreaded Global South drawn near. Her talks with the leaders who live and work in the area, in contrast, redefine the borderlands as “a place of dynamic innovation, growth, and potential” consistent with “classic American values of ties to the land, hard work, and entrepreneurialism.”

Stuck Moving: Or, How I Learned to Love (and Lament) Anthropology, by Peter Benson, Ph.D. ’07 (University of California, $29.95 paper). And now for something completely different: the University of Delaware’s anthropology chair melds his field with “the pop culture of my youth,” inverting the science to explore himself and his field, writing “as a white guy about angst and alienation in the privileged spaces” of his discipline and higher education. Whatever doubts may plague his peers, Benson ups the ante, foregrounding his own bipolar disorder, addiction, etc. The action begins “Stoned, sitting on the couch, glass pipe and bag of weed” at hand.

The Myth That Made Us, by Jeff Fuhrer, Ph.D. ’85 (MIT, $34.95). As populists on the right reject pillars of neoliberal economics (free trade, immigration, minimalist industrial policy), critics from the traditional center are raising a ruckus, too. The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s former director of research comes out swinging about “how false beliefs about racism and meritocracy broke our economy (and how to fix it),” his subtitle. Given unequal incomes and wealth, lousy jobs, etc., he proposes effective early childhood education, better school-to-work training, adequate minimum wages, health insurance, humane work schedules, and more.

Rich White Men: What It Takes to Uproot the Old Boys’ Club and Transform America, by Garrett Neiman, M.B.A.-M.P.P. ’20 (Legacy/Hachette, $30). The author, a serial social entrepreneur, draws on his fundraising experiences and other contacts with the 0.1 percent to attack “a central barrier blocking America from becoming an equitable nation…a collection of myths that justify inequality, which many rich white men believe in and market to the public….” Reflecting on his own privilege and powers, he aims to explain how to remake this country “into a nation that empowers every one of us to become free.”

Artifactual: Forensic and Documentary Knowing, by Elizabeth Anne Davis, ’97 (Duke, $30.95 paper). A Princeton associate professor of anthropology explores how various actors (forensic researchers, artists) tell and provide context for stories. But this ethnology of “knowing”—based on the decades of violence in divided Cyprus, with thousands of identified casualties and at least many hundreds of missing persons on both sides—is, sadly, applicable to so many other places around the world today. Davis’s subjects “work to locate, exhume, identify, and repatriate the remains” of those killed and buried in secret graves during the war, 1963-1974, and craft documentaries about the conflict. Her work, on understanding the “dynamics of secrecy and revelation,” is chilling and essential.

Our Hospital, by Samuel Shem (Berkley/Penguin Random House, $29). The fourth installment in The Healing Quartet of novels, which began with The House of God, a perennial favorite among members of the medical profession, brings matters very up-to-date as doctors and nurses struggle to provide care in a small town. The author, Stephen Bergman ‘66, M.D. ’73, knows the territory incredibly well (see “The Prodigal Doctor Returns,” harvardmag.com/comm-med-09). Readers of any background will get the context immediately from the opening page: “Late March 2020. Dr. Roy G. Basch was dead tired,” with an extra beat of meaning from those last two words.

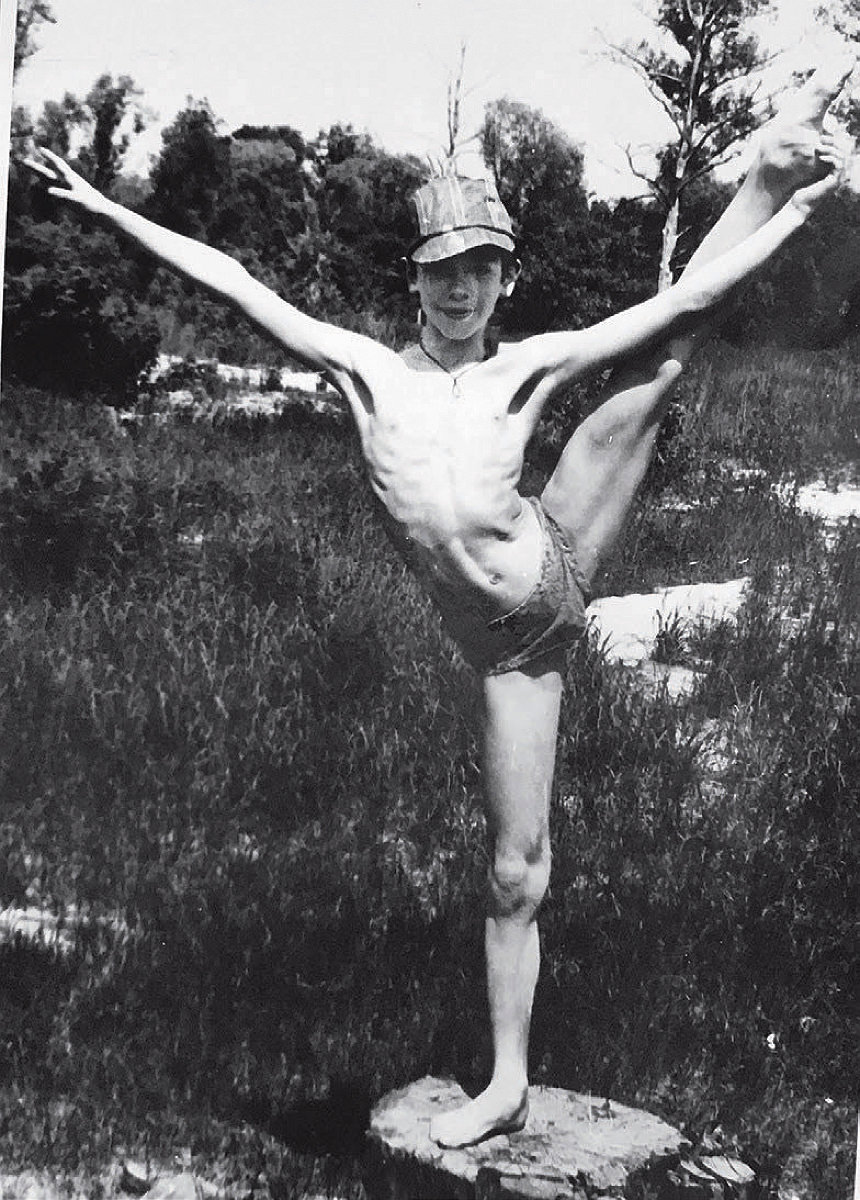

The Boy from Kyiv: Alexei Ratmansky’s Life in Ballet, by Marina Harss ’94 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35). A dance critic and translator assesses the work of perhaps the preeminent contemporary ballet choreographer, who has directed the Bolshoi, been artist in residence at the American Ballet Theatre, and is now at the New York City Ballet. Harss writes accessibly and authoritatively about this most ephemeral of performed art forms, describing her subject’s unlikely The Bright Stream, unveiled in New York on a 2005 Bolshoi tour—a “tractor ballet” farce set in the 1930s on a Soviet collective farm—as, somehow, “funny and silly and sad, filled with touching details that laid bare our flawed human nature.” Some of the source materials used in his interpretations of iconic ballets reside in Houghton Library’s Theatre Collection.

Body of Water, by Daniel J. Boyne, Ed.M. ’93 (Lyons Press, $27.95). “‘Big Ed’ Masterson shoved off from the Cambridge Boat Club dock and just sat there for a second, gazing at the half-lit sky and the still waters of the Charles.” So begins a murder mystery set in Harvard’s front yard, composed by a devoted rower. Allowing for that kind of prose, the jacket copy promises readers the inside dope on “the privileged world of Ivy League rowing, family ties, money, and sex,” in 198 compact pages.

.