On Thursday, during a Zoom media conference the day after announcing his retirement, Tim Murphy was informed by Harvard director of athletics Erin McDermott that no one could hear him because he had muted himself. In the oft-voluble Murphy’s 30 years at Harvard, this was a first.

The news that Murphy—formally, the Thomas Stephenson Family head coach for Harvard football—was stepping away was a surprise but perhaps not a shock. In October he will turn 68. This past season was a rugged one. Murphy was coaching with a heavy heart. His lifelong friend, Dartmouth football coach Buddy Teevens, died in September after being injured in a traffic accident the previous March. “Buddy and I had often talked that we would go out [from coaching] together,” Murphy said. Sometimes last season, particularly when he spoke with the media after a close game, the strain showed.

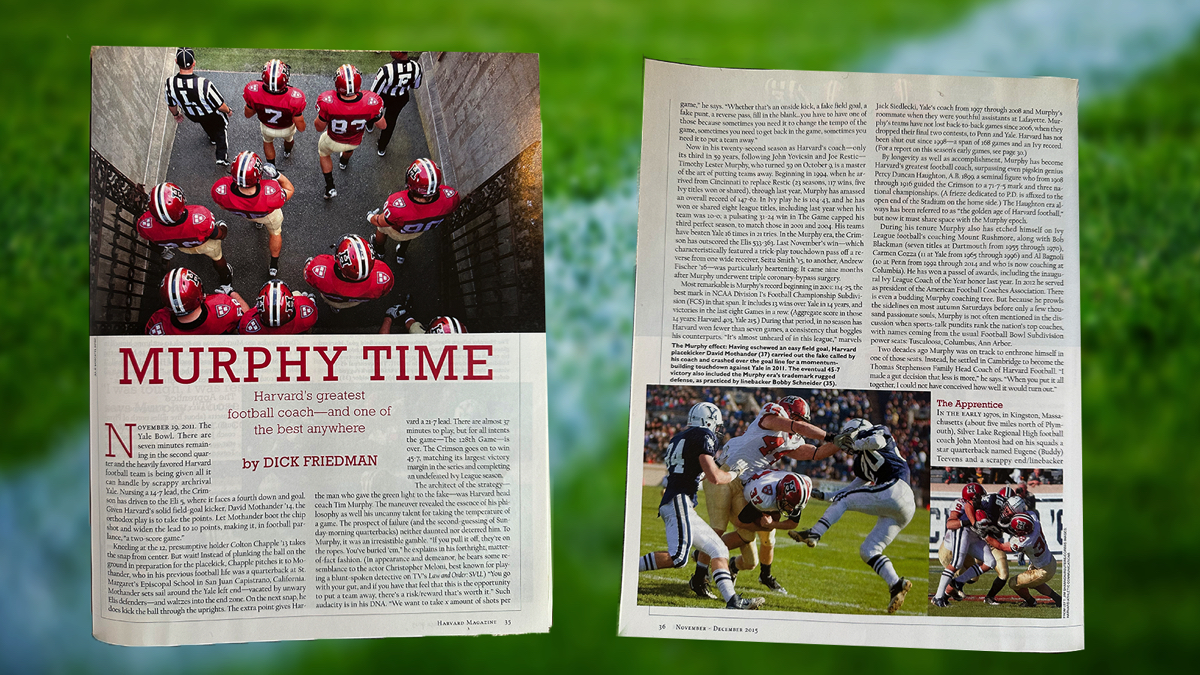

As tributes scrolled on social media from many of his 1,000-plus former players and 80-plus past assistant coaches, Murphy could take pride that he went out on top. In the 2023 season the Crimson finished 8-2 and shared the Ivy title with Dartmouth and Yale. It was Murphy’s tenth crown, outright or shared, tying him with Yale’s similarly iconic Carmen Cozza for most all-time. In a year that Harvard football celebrated its 150th anniversary, Murphy added two more record-setting milestones of his own: his 200th victory in Cambridge and his 141st Ivy League victory, surpassing Cozza as the winningest coach in league games. (Murphy’s final coaching record, including previous stops at Maine and Cincinnati, is 224-132-1.) Now, there would be no need for Murphy to pad his resume. A lock for the College Football Hall of Fame, he is not only Harvard’s greatest football coach but also is on the Mount Rushmore of Ivy coaches, along with Cozza, Bob Blackman of Dartmouth and Cornell, and Al Bagnoli of Penn and Columbia.

On Thursday Murphy acknowledged the toll his job had taken. “Coaching college football is not dog years, but it is very intense,” he said. The decision to step down was clinched by his spouse, Martha. She had drawn four zeroes on a whiteboard. “My wife pointed out to me some really weird sort of numbers”—namely, that four of ’23’s milestones (30-year tenure, 200 wins, 10 titles, 150th anniversary)—ended in a zero. “She goes,‘Zero, zero, zero, zero. I think someone's trying to tell us something. It's time to pack it in.’”

Last season’s title came after the Crimson had been picked in the pre-season media poll to finish fourth. Harvard began the season without an experienced starting quarterback or running back. By November sophomore Jaden Craig had seized the quarterback reins, and junior running back Shane McLaughlin had become a first-team All-Ivy selection; after the season McLaughlin was elected 2024 captain. Moreover, a host of other previously untried players had emerged to play important roles. Accordingly, many observers deemed this Murphy’s best coaching job during his tenure.

Murphy is one of many successful longtime college football and basketball coaches to step down recently. Earlier in the month Alabama football coach Nick Saban, 72, a friend of Murphy’s, had also announced his retirement. Age is not the only reason for the departures. “College football is changing dramatically, and not for the better,” Murphy said on Thursday. “It’s absolutely, positively professional football, but without any rules whatsoever….Right now it’s [for] the highest bidder, and the rich get richer.” Coaches in college sports now must contend with such developments as student-athletes school-hopping via the transfer portal and haggling for the most lucrative name/image/likeness deals. (In fact, with the coaching change, Harvard’s players will be granted 30 days to put their names into the transfer portal should they desire.) This is not what coaches such as Murphy and Saban signed up for. Murphy’s system was predicated on players being around for four years and usually submitting to two or three years of careful apprenticeship before they would be entrusted with significant playing time.

For the foreseeable future Murphy will be around his base of three decades. “In a very small way,” he said, “I will consider myself connected to Harvard for life.” He now will be free of the many obligations that have consumed him: game-planning, recruiting, and dealing with the pesky media. (On a personal note, I can say that he was unfailingly cooperative even after difficult losses or rough seasons. Sometimes he was the one doing the consoling.) It remains to be seen whether he will continue to run on fabled “Murphy Time” (the title of this magazine’s 2015 profile of the coach)—starting all his engagements five or more minutes early.

During the upcoming hunt for his replacement, Murphy will be hands off. If asked to supply advice and counsel, this time he will not be muted.

“We’ll do a great job with the search, led by our director of athletics,” he said. McDermott, who announced a nationwide search, said she’s looking for someone who knows the game and who can win, but who is also an “educator-coach” who “embraces the Ivy model.” One thing we know: the brave man who takes the job will have an impossible act to follow.

And here’s a wild notion: this month, besides Murphy and Saban, two other foxy future Hall of Fame coaches, Bill Belichick of the New England Patriots, age 71, and Pete Carroll of the Seattle Seahawks, 72, left their jobs. Shouldn’t some enterprising NFL team make a package deal for this over-the-hill gang? Between them, there’s not a play they haven’t seen.