Joyce E. Chaplin, Phillips professor of early American history, is a multitool scholar, working across fields including the history of science, climate, colonialism, and environment. That breadth of expertise is reflected in her affiliate appointments, ranging from the department of the history of science to the Graduate School of Design’s department of landscape architecture—and others within and beyond Harvard.

All those threads of inquiry come together in her new book, The Franklin Stove: An Unintended American Revolution (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). It at once pursues inquiries into a polymath about whom Chaplin has written before, material culture, what she calls a “project” (a set of inventions, investments, and improvements pushing some solution to a problem ever forward), and Pennsylvania’s central role in the making of early industrial America.

Even more, it is an exploration of American “techno-optimism,” and of a multifaceted attempt to address eighteenth-century energy and climate crises. The former concerned the looming exhaustion of native forests, as colonialists burned their way through the natural bounty to fuel their fireplaces; the latter, the Little Ice Age, which brought a period of sometimes-devastating cooling to the North Atlantic from roughly 1300 to 1850.

This excerpt, from Chaplin’s introduction, conveys what was at stake then, and why it pertains now. —The Editors

-Make haste slowly

—Poor Richard

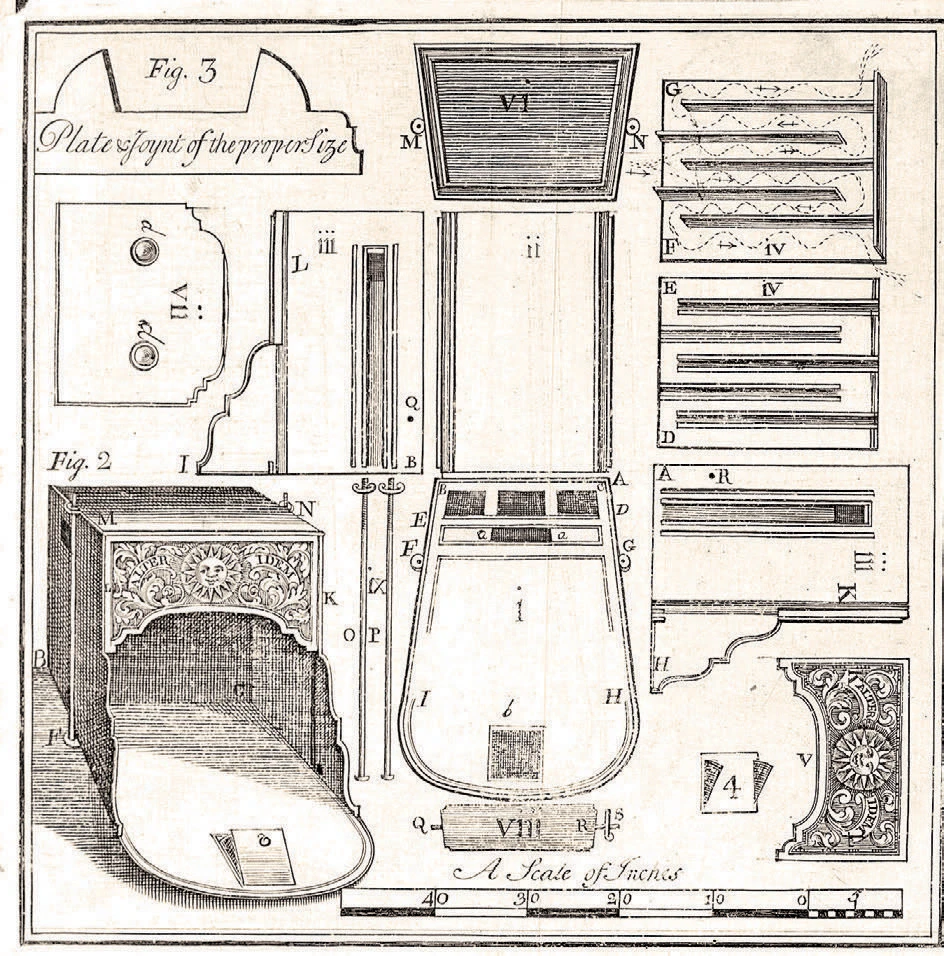

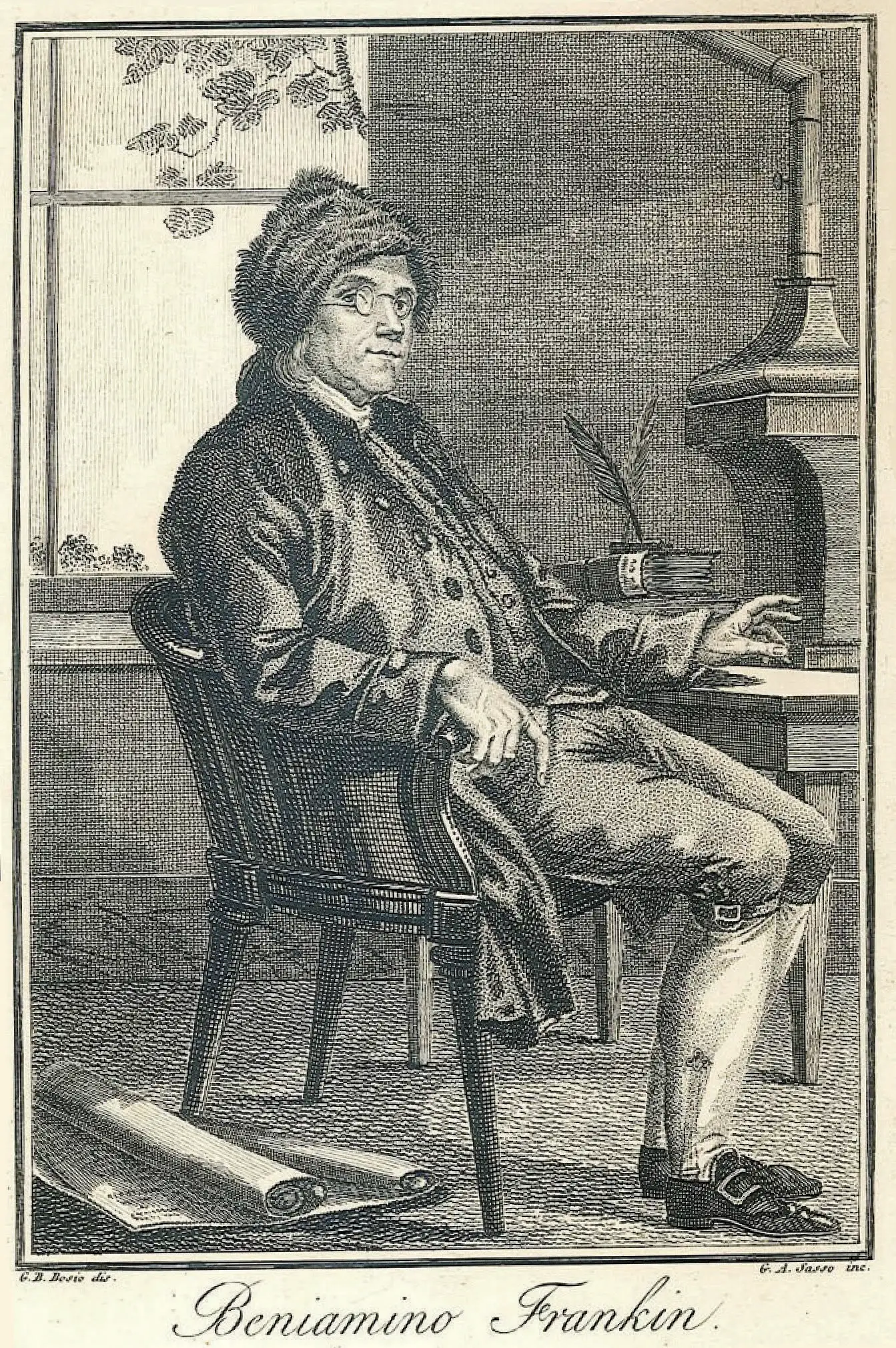

Yesterday’s technology is trash, or maybe it gets recycled—unless it goes to a museum. Those were the fates of Benjamin Franklin’s famous stoves, only one of which survives and now resides in the Mercer Museum in Pennsylvania. It’s roughly the size of a side table (30.75 by 27.5 by 35 inches) and, like many side tables today, originally came as a flat pack with instructions for assembly into what the museum describes as “a cast-iron stove.” But it wasn’t just a physical thing, forged from iron. The stove was a hypothesis. Franklin was proposing that, armed with science, he and others could invent their way out of a climate crisis, creating comfortable indoor atmospheres for buyers of new stoves during a period of natural cooling (yes, the exact opposite of our problem) now called the Little Ice Age. He believed his stove could accomplish this in spite of another, related crisis: a widespread shortage of wood fuel. And he conceived of his invention as equal parts scientific instrument and home appliance, its many iterations identifying basic principles of atmospheric science that might allow him to figure out why the climate was changing in the first place. It may seem ironic that an old wood stove is now coddled by a museum’s modern HVAC system, but it’s a logical outcome. The search for better heating was part of a seismic shift in material life, the most important revolution of Franklin’s era: the industrial revolution, with its historically unique rate of burning things, eventually resulting in the artificial heating of our entire atmosphere.

Given the high hopes today for inventing a way out of our own climate crisis, the history of the Franklin stove is useful, even if the physical object no longer is. Physical objects, I should say, because Franklin didn’t invent a stove—he invented five of them. He kept reinventing them because he and his contemporaries were worried (like us) that two grim trends—climate change and resource depletion—were converging on them, with the added threat (like us) that war might at any time further compromise access to resources; Franklin lived during what historians call a Second Hundred Years’ War, beginning in 1688 with the War of the League of Augsburg (before his birth) and ending with the close of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, after he died, taking in the Seven Years’ War and American War for Independence along the way.

With five different versions, “the” Franklin stove was an ongoing project, preoccupying Franklin for more than half of his life, from 1738 to 1784, and eventually involving a great many other people, including the proprietors and workers at three Pennsylvania ironworks, a couple of Franklin’s brothers, his London landlady and her daughter, several of the era’s biggest scientific names, many aristocrats who liked buying the latest tech, two famous steam-engine inventors, and the chief of police in Paris.

It’s from Franklin’s era that we inherit our techno-optimism, hope that a single device might solve a huge problem. Faith in technology was part of an eighteenth-century rage for “improvement,” the belief that planning and scientific knowledge could better the human condition. As an early incarnation of the charismatic scientific inventor who makes big promises, Franklin proposed a way to manage an emergency with a technical device whose virtues, he shrewdly hinted in his marketing materials, were uncountable: “&c. &c. &c.”

We now expect even more from technology, maybe too much. Electronic consumer devices are our friends, glowing presences that make us feel autonomous and yet connected, an intoxicating combination. AI is our rival, a hypothetically self-governing power that might do us in and replace us. Other new technologies are our saviors—electric cars, solar panels, heat pumps, carbon capture, geoengineering, gigantic orbiting parasols—that are supposed to solve the climate crisis without our having to make any other changes to our society or economy. But all three of these possibilities ignore how new inventions tend to remain tethered to their human creators and users. Devices depend on the social relations around them; their designers encode preferences into them, deliberately or inadvertently. We should ask: what gets encoded when technology is supposed to tackle climate change, as in Franklin’s era?

The Little Ice Age was the biggest change in climate before our own. This period of inter-glacial cooling in the North Atlantic lasted (roughly) from 1300 to 1850. It wasn’t global, nor caused by human beings, but its effects were sometimes devastating. People disagreed as to whether they could warm up the weather, but they knew they had to adapt to the cold. And so, in their adaptations—including a growing reliance on science and technology—Franklin and his contemporaries conducted a kind of fire drill, one we can study in retrospect.

If the stoves were hypotheses about inventing a way out of a climate crisis, their story shows that surviving climate change is not just a technical problem: there is no magic bullet. Climate change is a social and political problem, one with a much bigger history, though one early and important chapter conveniently fits into a device the size of a side table.

The Franklin stove is an icon and a mystery. It’s always there on the lists of the celebrated man’s celebrated inventions (lightning rod, bifocals, glass armonica, swimming fins, stove …), but there are few serious investigations of it. Many details about material life in Franklin’s era get brushed away, as if they’re traces of backwardness. This is above all true of energy use.

Consider the movie Barry Lyndon (1975). Famously, Stanley Kubrick shot footage in historic places, used only natural light or candlelight, and demanded period-correct costumes and makeup. But in the entire film, there’s not a single lit fireplace. In one scene, the title character morosely chops wood. It’s as if getting fuel and keeping warm worry only the powerless rustics, while the rich characters have hidden HVAC systems and keep their fireplaces just for show.

Kubrick began filming Barry Lyndon in spring 1973, right before the first energy crisis, but more recent representations of colonial America—many crises later—follow its odd logic about indoor heat. In John Adams (2008), John and Abigail show their sturdy origins by chopping and toting firewood at home in Massachusetts. And they share scenes with some fireplaces lit for specific tasks, like ironing clothes or burning government documents. But as in Barry Lyndon, the fires fade as the Adamses ascend the social ladder: no hearth gleams in the episodes set during Adams’s diplomatic service in Europe. Things are better in the miniseries Franklin (2024), where the French foreign minister, at least, has a cheery fire in the winter of 1776 when Franklin arrives, though no one else does. A couple of winters later (episode four), everyone’s chamber is aglow, but only with the open, wood-burning fireplaces Franklin deplores. The fireplaces are set design, signaling a past that’s passé—except when that amazing transhistorical HVAC is softly purring somewhere out of sight.

Beware any household fire that does burn in a historical film, however, because it’s usually there to signal the wretchedness of premodern life. Consider the doomed colonial family in The Witch (2015), whose passage to death and damnation is tracked by the growth of their woodpile, which in the end collapses onto the dying puritan patriarch who built it up for a winter’s warmth in which no one will live comfortably.

The fires burn to highlight the movie’s real form of energy: sorcery. The assumption seems to be that colonial people must have had some demonic equivalent to modern technology, the wood-burning kind being so obviously ridiculous.

The real horror was not, in fact, having to chop your own wood, but having no wood to chop. Hollywood’s disdain for material needs reflects a modern prejudice that stockpiling firewood was beneath anyone of consequence, reflecting how fossil fuels have, for a great many people, made energy use magically invisible.

Meanwhile, most historians also edit early America’s fuel and fireplaces out of the picture to keep the spotlight on other developments, above all the American Revolution. But is that the most important transformation of its era? The events bundled under the label of industrial revolution, with its fateful turn to carbon-based energy, may have been at least as momentous. As I write, plans are afoot to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the United States in 2026. But 2030 marks the date when, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has warned, CO2 emissions must be halved to prevent the worst consequences of anthropogenic climate change.

Franklin, famous American founder, may have had a greater impact on this other revolution, whose consequences now overshadow everything else.

The technology that epitomizes the industrial revolution is probably the coal-burning steam engine, ancestor of anything powered by fossil fuel, including any electronic device that gets its spark, ultimately, from coal- or natural gas-fired power plants. The steam engine’s eighteenth-century inventors wanted to escape the limits of organic energy—sun, wind, water, wood, and food for humans and animals—by burning coal to generate power; they also wanted to make money and help other people to do the same—industrialism is the directly planet-eating part of modern capitalism. Few people in Franklin’s era (including Franklin) foresaw what steam power would do, however. In their lifetimes, most engines pumped water out of mines, dirty, dangerous, and out-of-the-way places most of them would never visit. Meanwhile, they thought new heating designs, distributed among too many households to count, might have huge impact. By the 1780s, improved fire-grates would be one of the most commonly patented consumer items in Great Britain. And indeed, household consumption of coal, long before factory industrialization, was the gateway to fossil fuel dependence. Franklin designed his first stoves to consume wood—and conserve wood—but in the end he built heaters that burned coal.

Really, what Franklin and his fellow stove inventors thought they were inventing was an artificial atmosphere big enough to live in. It was this new idea, eventually to converge with the relative novelty of burning coal, that was the first step towards central heating (and a regulated indoor climate) becoming the default in the industrialized world. Iron stoves were history’s first consumer durable, ye olde ancestors of washers, dryers, dishwashers, and HVAC systems. Keeping warm under Little Ice Age conditions was a tall order, and yet the era’s many heating innovators were promising indoor climate control that saved fuel. An artificial indoor climate was a snug hub of new confidence that nature could be controlled, defying conditions that might otherwise have caused fatalism.

Franklin’s more distinctive ambition was to use indoor atmospheres to figure out the big one outside. His first two stoves generated his primordial insight: through convection, they heated the first atmosphere he investigated, a room in his family’s home, which became his model for interpreting heat and the motion of air within the planet’s atmosphere. Having turned the outside in, harvesting natural resources to control indoor climates, he then turned the inside back out. He conjectured that the Northern Hemisphere’s climate was colder than it had been in the remote past. He described climatic phenomena (such as Atlantic storm systems and the Gulf Stream) as complex thermal systems that crossed multiple latitudes. He hypothesized that volcanic activity could cool the atmosphere.

Finally, Franklin examined the human impact on natural atmospheres. He questioned whether the deforestation of North America would result in a warmer climate, something his white contemporaries insisted was a benefit of their constant extraction of firewood, but which he worried might not work—or else might lead to catastrophic overheating. Relatedly, he observed what we now call microclimates, often the result of human modifications to dense urban spaces. Also, he refused to accept that atmospheric pollution from household fires was inevitable and tried to design heating to minimize it—a friend teased him for being a “universal Smoke Doctor.”

Franklin’s efforts, widely discussed, show that awareness of links between human and natural atmospheres began in the eighteenth century. True, no one proposed that collective, everyday fuel consumption might eventually transform the Earth’s entire atmosphere. But several eighteenth-century observations suggested that, if humans could modify atmospheres indoors, they might be forging a different one in the world beyond. Two centuries (plus) later, we live with the consequences.

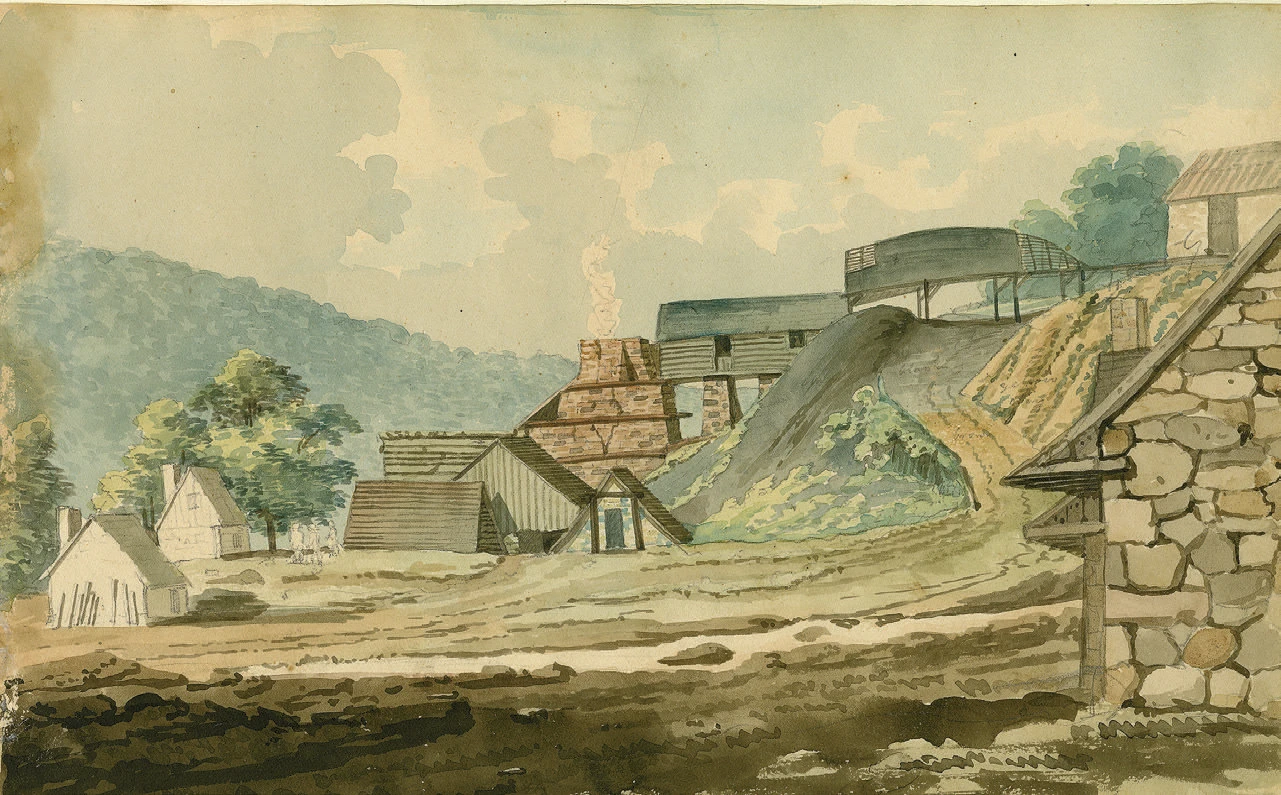

Like any successful revolution, the creation of modern industrial society produced deep cultural inertia, a thousand reasons not to change a thing. Most revealingly, Franklin’s adopted colony of Pennsylvania was in the vanguard of this new materiality, which makes his fireplace (and fire drill) distinctively useful to consider. Once upon a time, the industrial revolution was assumed to have begun in Europe, especially Britain, motherland of coal mines and factories. In fact, Europe’s overseas territories supplied much of industrialization’s raw material and capital, and some of its ideas—including Franklin’s. Above all, Franklin’s colony was the most obvious prototype for North American industrialization.

Virginia has been proposed as the quintessentially American of the original states because it was the first English colony to invest in enslaved workers from Africa, the first to forcibly remove Native American populations, yet also a leader in creating the independent nation, given Virginia slaveholders’ outsized role in the Revolution and early republic. This idea of Virginia as the United States in miniature does not acknowledge, however, the nation’s eventual industrialization, which is usually associated with the northern colonies or states, especially New England and New York, and later with the Midwest, especially Chicago.

But Pennsylvania contained all these elements. It would by the nineteenth century be called the Keystone State for its geographic position, midway among the thirteen original states, and for being the heart of the American Revolution, the place where both the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution were written. It would also be the heart of US industrialization, the first American state to rely on free, waged labor, and first to produce and burn coal on an industrial scale, then do the same with liquid petroleum. These outcomes had their genesis in the colonial iron industry that cast Franklin’s stoves. The colonies were already, by the 1770s, producing one-seventh of the world’s supply of iron, with Pennsylvania not just a follower in industrialization, but a leader.

The colony’s early industrial revolution was distinctive, as well, in exposing the limits of organic energy, the fuel and food produced photosynthetically by the sun. Long before Pennsylvania became a land of coal-burning, steel-forging factories, white settlers were burning through woodlands appropriated from Natives at a dangerous rate, and the colony’s ironmasters were exploiting every kind of labor available, including underfed enslaved people. In his project, Franklin would validate the European-led transition to coal, but only by hiding the American aspects of his original stoves, their reliance on Indigenous removal and forced labor. This was cheating in any number of ways, but especially by foreshadowing the biggest cheat of all: industrialization’s promise, through fossil fuel, to transcend the limits of organic energy sources like wood and human labor, and therefore triumph over natural limits entirely.

That premise bolted a glitch into industrialization because nature always has limits. Franklin both knew and denied this, much the way we know but deny it. He would hypothesize that plentiful natural resources guaranteed rapid population and economic growth—gloriously apparent in the British colonies—but admitted that even American abundance might falter, hence his fuel-conserving stoves. The sunnier half of his hypothesis became the core of growth economics, correlating human happiness with development of natural resources.

This too was part of an age of improvement, when people were cooking up projects for profit on every possible scale. Adapting the Greek word for household, oikos, the English used “economy” to describe household management from the 1440s onward, then “political economy” to plot the wealth of entire nations—the origin of modern economics—starting in 1687, not 20 years before Franklin was born. Reflecting his era’s confidence that wealth was easy to generate (and enjoy), he would describe human material desires with the most outrageous word possible: “infinite.” No wonder he thought consumer discipline might be necessary; no wonder he didn’t assume it would be a universal virtue. Only much later, in 1875, would “ecology” describe nature’s households, belatedly recognizing a symbiosis of humans and nature, but with no assumption that nature can support infinite economic growth, an expectation, for better or worse, made in Pennsylvania.

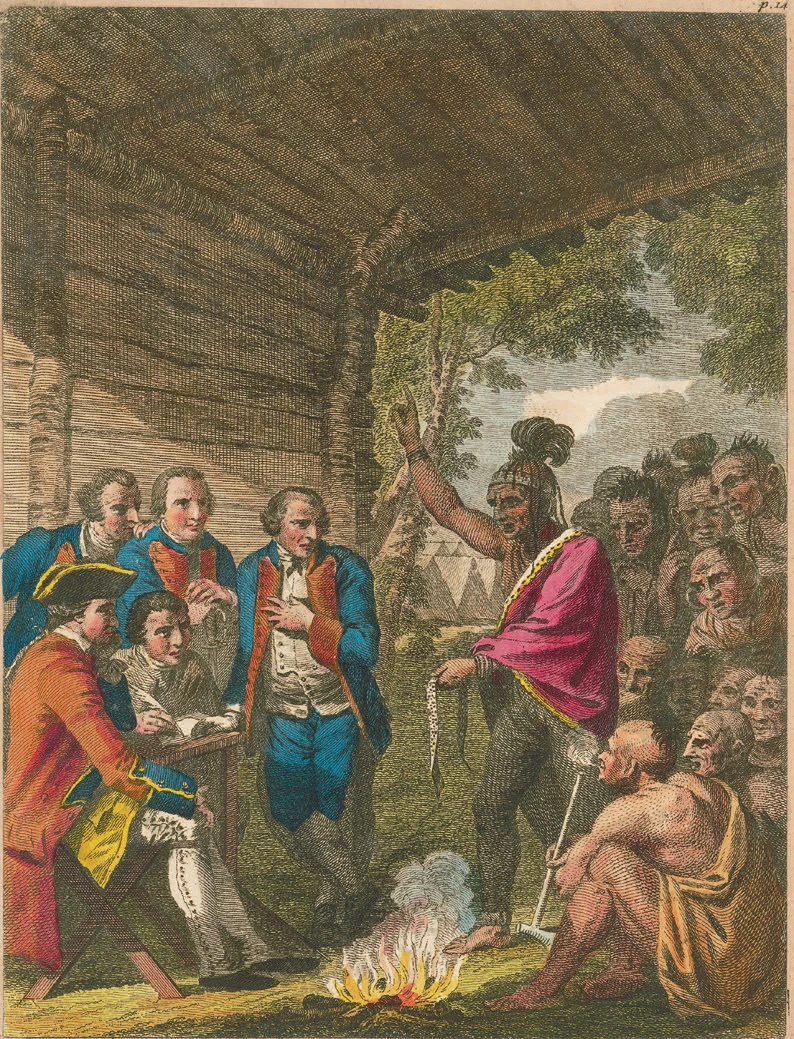

To promote economic growth, Franklin had to ignore two powerful Pennsylvanian counterexamples. First, Indigenous Americans rejected an ethics of human command over nature; they did not separate economy and ecology. For them, natural things were not passive assets. They burned fuel as part of diplomacy, for instance, in council fires that united people and even nonhuman species. It’s no use thinking Franklin didn’t know this. As official printer to the colony of Pennsylvania, he printed the treaty negotiations conducted around council fires. Those treaties, which now define Indigenous rights in relation to the United States, have always rejected the industrial revolution’s split between humans and nature.

Likewise, in suggesting that humans derive economic value from material things but are not raw materials themselves, Franklin ignored how enslavement violated this logic. Pennsylvania’s Native Lenapes and its enslaved Black people protested this debasement, decades before the state launched a formal program of emancipation that Franklin would in the end support, rectifying his earlier assertions that some people made economic value while others were made into it, including some of the ironworkers who produced his stoves.

In the end, Pennsylvania’s history shows that industrialization was not—is not—an irresistible force. Some people have suggested that coal prompted abolition, steam power making slavery seem unnecessary and backward. The corollary is that without fossil fuels, humanity will descend into a Hobbesian war of all against all. But Pennsylvania’s history doesn’t bear this out. Some people questioned and resisted enslavement long before the state’s dependence on coal, let alone petroleum. Franklin, for example, wanted to improve everyday life by crafting stoves made by enslaved workers, only later realizing that this amalgam of conservation and exploitation was not a step forward—an ethical dilemma for which he (and others) did not suggest coal as an easy fix. Liberation and societal uplift are possible because people make them possible, not because nature hands them the means to do it.

Franklin’s project was both the violent capitalist machine in an Edenic garden and far-out, new-age, redeeming alt-tech.

As an adaptation to climate change, Franklin’s stove project met only one of three desired criteria: it worked (certainly enough to be adopted and imitated), but it validated a short-term solution—fossil fuel energy—with its own colossal drawbacks, and, at least initially, it accepted social inequities rather than confronting them. The stove’s story is complex—and must be told that way. A progress narrative might celebrate the stove for using applied science to improve material life and lay groundwork for climate science, with these good outcomes canceling out anything else. A tragic narrative would, conversely, stress the human costs as outweighing any benefits. I think the story is incomplete without all its elements. If we are to understand energy and climate and technology in their fullest historical impact, comfortable domestic spaces must feature within them. Franklin’s project fits into optimistic and pessimistic visions of American technology; it was both the violent capitalist machine in an Edenic garden and far-out, new-age, redeeming alt-tech.

A complex history suits a complex challenge. Climate change is what ethicists call a wicked problem, something with so many variables, with overlapping (and mutating) qualities, that solutions must themselves be multiple, overlapping, and quickly adaptable. Technologies never solve wicked problems unless they’re linked to social transformations, because technology (correctly understood) is always a system of things and people. If anything, inventions that tackle such problems risk embodying any bias that fueled the crisis in the first place. Today’s solutions to climate and energy are unlikely to be free of the legacies of colonialism, for example, unless the inventors confront that history.

A project leans forward in time—it’s an experiment projected to run into the future. The Franklin stove, object and project, was supposed to solve historically atypical cold weather and the threat of future deforestation and loss of fuel. As Franklin put it: “By the Help of this saving Invention, our Wood may grow as fast as we consume it, and our Posterity may warm themselves at a moderate Rate, without being oblig’d to fetch their Fuel over the Atlantick; as, if Pit-Coal should not be here discovered (which is an Uncertainty) they must necessarily do.” Franklin believed human technology could mitigate climate change, but he knew this begged other temporal questions, especially in terms of growth economics, predicated on change over time, and demanding new energy, as with that “Pit-Coal,” which most definitely would be discovered in Pennsylvania, just after his death.

If a project runs into the future, we are Franklin’s “Posterity,” participant-observers in a continuing experiment in energy efficiency and resource conservation. Can climate-crisis technology operate on a suitable timescale? How fast can any adjustment be made, can it keep pace with population growth or consumer demand, and might it introduce a competing chronology in which resource depletion or toxic emissions undercut any benefit? The problem is choosing and implementing enough solutions in time. This is a particularly wicked feature of the wicked problem, the mismatch of timescales. Consumption of carbon-intense energy has, in a matter of centuries, damaged ecosystems that are thousands of years old and compromised an atmosphere millions of years in the making. Now, we need actions even swifter than those that brought us to this predicament—but without somehow making things worse.

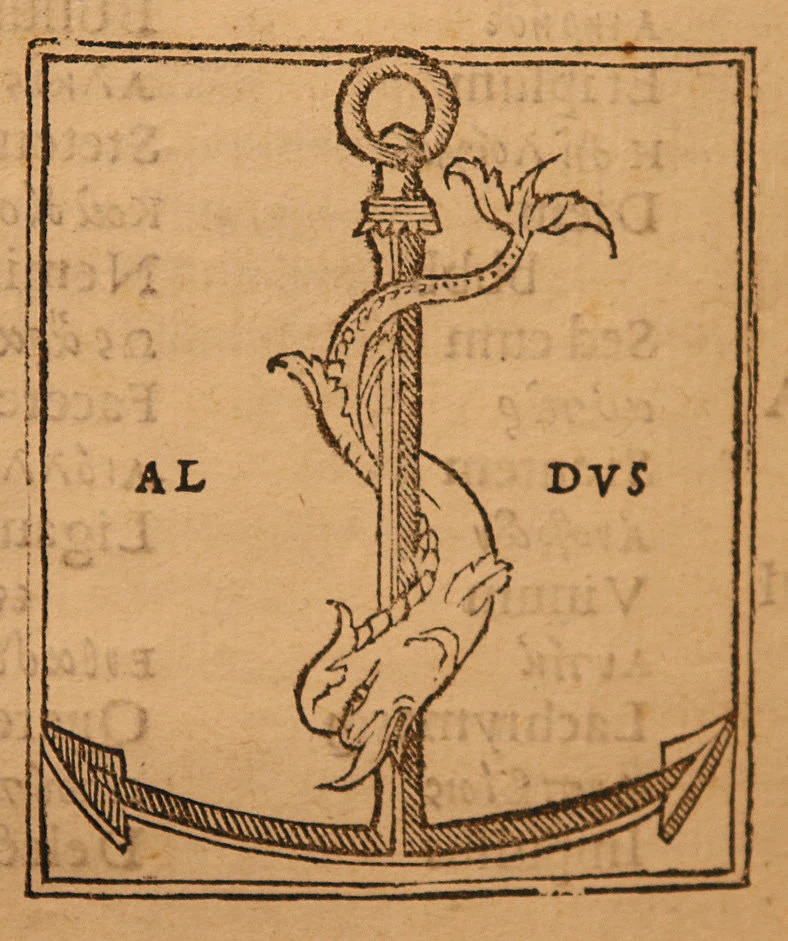

For all his faults, Franklin had some good advice about this. His famous almanac’s alter ego, Poor Richard, adapted a Latin proverb, festina lente, to advise that to get anything important done, you’ve got to “make haste,” but, paradoxically, you’d better go “slowly.” Since ancient times, people have translated the saying into visual emblems: a tortoise, proverbial for its steady progress, zips along with a sail rigged on its shell; a dolphin, a creature built for speed, is tangled round an anchor, which slows it down.

Each design suggests that technology can improve on nature, but that nature matters, too.

Festina lente: both haste and resolve are necessary. To fix a wicked problem, people must get moving, but with intelligence, correcting errors both old and new as they go. The worse the problem, the greater the need for speed but also care. In any techno-optimistic rush to invent a way out of our current crisis, remedies require the swiftness of a sleek dolphin, even as awareness of errors committed in the past must be a steadying anchor, which I hope this history of Franklin and his stoves provides.