Romolo Del Deo ’82 knew his sculpting career was going well. In his opinion, perhaps too well—unsustainably well. He was teaching at Harvard shortly after graduating himself, receiving grants, winning awards. The whole “system” of academic art seemed to embrace him, “and if a system likes you, and if you know how to work the system,” he said, “it’s like you have a magic wand.” But he was becoming less connected to sculpting itself. “I felt like the work I was doing belonged to a sort of analog version of me,” he said, “a Romolo who was on a career path going somewhere, who made sense to everybody.” So, with the pressure on him to create a “justifiable” career in the arts, he decided to do something that made little sense and was objectively bad for his career: he quit teaching, moved to Italy, and isolated himself on a Tuscan mountaintop.

The house he occupied was haunted, he thought, but in a good way. Looking out at the rolling hills, he thought about the people who had been making art for thousands of years, letting their surroundings—not career strategy—guide their work. He sculpted much of the day and, on the side, helped restore minor cultural sites for the Italian Ministry of Culture, standing on 60-foot scaffolds, washing fifteenth-century frescoes. Miraculously, 500 years of candle soot wiped away, and the artwork looked fine. Maybe, as contemporary art trended toward synthetic materials and improvised construction, there was something to learn from work that could last for hundreds of years. Maybe, Del Deo thought, “there’s a valid argument to think a little more archaically.”

Four decades later, he is still following that impulse. He is widely known for his contributions to the “Long Art” movement—which emphasizes slower processes as a way to discourage environmental waste in artistic practice—and as a proponent of classical techniques and materials that endure. Drawing inspiration from the ocean and casting his final work in bronze, he has dedicated his life to making art that is at once sustainable and sustaining.

Del Deo’s decision to pursue art wasn’t surprising. His parents, Josephine and Salvadore, were among the leaders of the Provincetown, Massachusetts, arts scene and the founders of the prominent Fine Arts Work Center. Artists constantly streamed through his childhood home to study painting with his father—and to sleep on the sofa. Del Deo, whose formal schooling was delayed due to a severe neurological injury, spent time in his father’s studio. His first exposure to sculpture came at five when Salvadore received a commission. “I thought, ‘My father is a God!’” he said. “He’s making this giant metal man, welding stuff out of scrap metal.” Del Deo used his father’s extra modeling clay to build toys that the family couldn’t afford. The clay-wheeled toothpick trucks weren’t elegant, but they were Del Deo’s thoughts realized. “I needed a language,” he said, “and that language was sculpture.”

This idea became salient when he entered school and discovered that he was severely dyslexic. Struggling to learn the alphabet, he reached again for the clay. (He didn’t learn to read until fourth grade.) Though his father enrolled him in painting lessons when he was 13, he was much more interested in sculpting and studying marine biology—learning about the local biome, collecting specimens, modeling his finds. It was partly his love of the Harvard Museum of Natural History, where his mother took him, that drew him to the College. It seemed pleasant to end up among the flowers and butterflies, the giant squid.

In a gap year before college, Del Deo studied sculpture in Italy. He returned, excited to take a sculpting course at Harvard with renowned Greek artist Dimitri Hadzi, only to be devastated when Hadzi told him that he couldn’t accept freshmen. Del Deo ran to the local art supply store, bought some Roman wax, and had his friend—football star Mike Rapposelli ’82—pose shirtless for him. Just before Hadzi had finished interviewing upperclassmen for the course, Del Deo barged in with the wax model, still warm and soft from the alcohol lamp. He got in.

Del Deo flew through the formal sculpting program and also studied archaeology and anthropology, completing a thesis on the use of color in ancient Greek sculpture. Upon graduation, he began teaching in what is now the department of art, film, and visual studies. He was popular among students and less popular among faculty and administrators, who told him to stop encouraging undergraduates to abandon their career trajectories and pursue art. Instead, he quit the job, abandoned his own trajectory, and moved to Italy in 1984. There, he drew inspiration from the natural world and the art that had lasted so long that it seemed almost natural itself. One sculpture, “Melpomene,” named for the muse of tragedy, is 20 feet tall, missing its head and one wing. The texture of its gnarled bronze resembles the wood that washes up on Cape Cod’s beaches.

When he moved to New York a few years later, this quality of earthy permanence helped his work stand out. Del Deo cast most of his sculptures in bronze and experimented with faces and figures that resembled ancient Greek or Italian art. He lived in New York for 30 years, teaching, restoring art, and sculpting works that have been displayed in galleries and exhibitions across the world. In 2022, his “The Tree of Life Which Is Ours”—a monumental winged torso and head in bronze atop a winding wood trunk and stone base—was shown at the Venice Biennale.

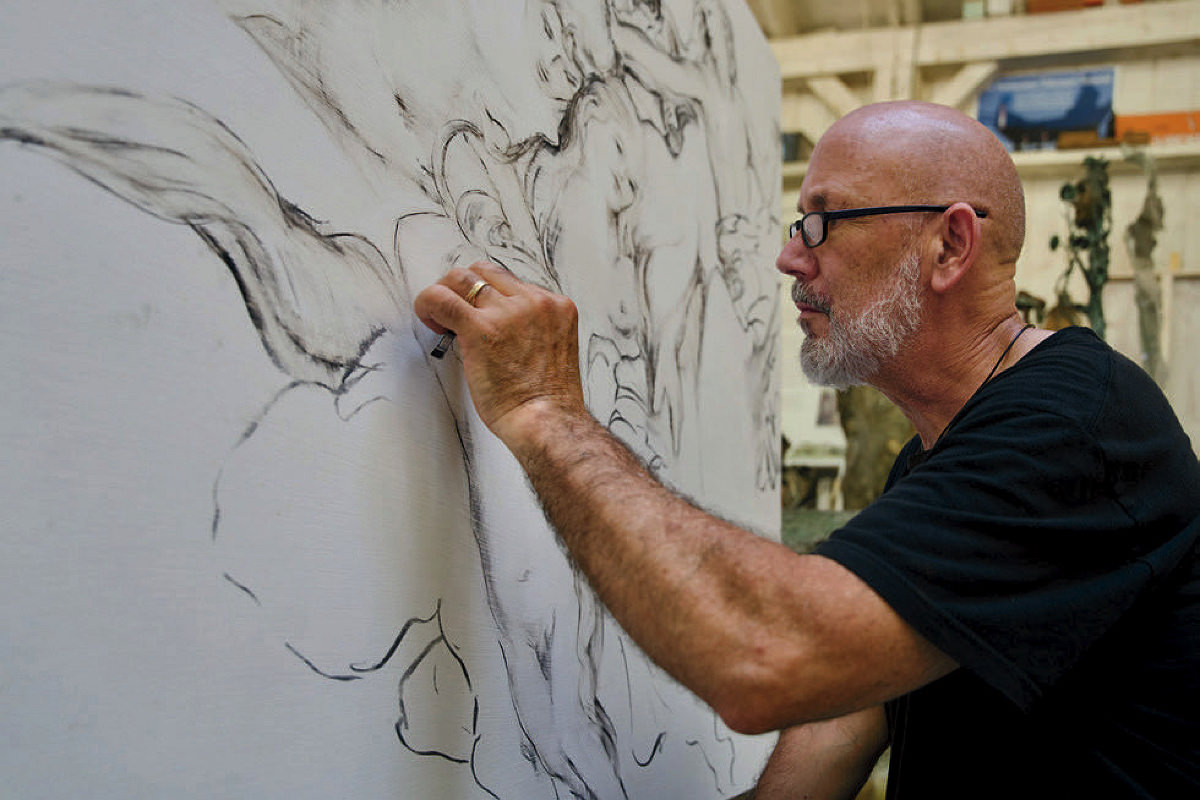

In 2011, he moved back to Provincetown. He lives next door to his father, now 95. Around lunchtime, they head to their studios together and return in the evening for a shared dinner. On an evening in October, Del Deo’s studio is packed with in-progress sculptures, tools, and materials, though he doesn’t view the space as busy. “If I can walk around,” he says, “it’s empty.” He shows off a recently discovered piece of driftwood that will work its way into a future sculpture. Before then, he’ll cast it in wax, trim off certain sections, and create a mold before casting it in bronze. From there, he’ll break pieces off, transform it, destroy it, put it back together. “There’s always a direction,” he says, though “a lot of times, it’s not clear what it is. The ‘Aha!’ moments come frequently, but most of the time, they’re wrong. It’s all part of the process. The work takes a long time. It’ll last a long time, too.”