Nearly six feet tall, Winthrop Bell (A.M. 1909) was a handsome, blond, blue-eyed philosopher, prisoner of war, and MI6 spy.

An athletic outdoorsman, he had survived arduous employment as a surveyor in the wilds of northern Canada before coming to Harvard. But he wasn’t just good looks and rugged backstory. Sackville, New Brunswick’s, newspaper described his “amazing capacity for hard work” and “studious, friendly, gracious, attractive” personality. The philosopher Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, called him brilliant.

Recently declassified papers reveal him as the earliest enemy of the Nazis. As British secret agent A12 reporting from Germany, he gave the first warnings of the nascent Nazi ideology in 1919, and later warned of their plans for race war. Two decades later, in 1939, he published the first predictions of the upcoming Holocaust.

Bell was born in Halifax in 1884 and raised in a prosperous, academically inclined family. His father, Andrew, owned a successful ship-outfitting business. He was a genial, humble man who gladly stood against injustice. Winthrop’s mother, Mary, a perfectionist unto exhaustion, studied music in Boston before teaching piano in Sackville. The parental tendencies to perfectionism, humility, geniality, musical appreciation, and righteous anger combined

in their son.

After graduating with honors from prestigious Mount Allison University in Sackville, Bell came to Harvard to study philosophy in 1908, at the “greatest department in the greatest of universities,” as his professor Ralph Perry put it. Harvard pragmatism taught that the world is full of problems, and thinking is designed to solve them.

After receiving his A.M., Bell continued studying philosophy at Cambridge University’s Emmanuel College and Leipzig. In 1911, he arrived at Göttingen, Germany, to study with Husserl. Bell was making his final dissertation revisions when Britain entered the Great War in August 1914. As a Canadian, and thus a British subject, he was an enemy alien.

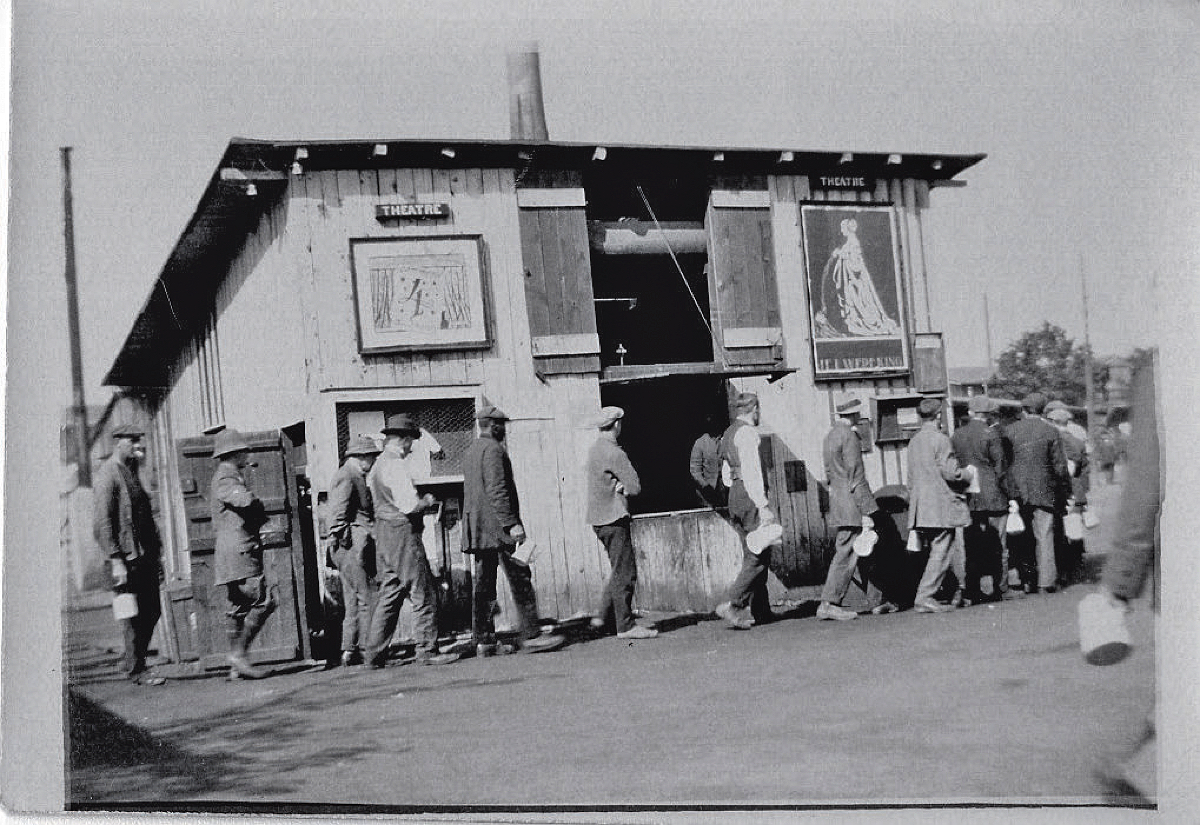

Soon he fell under suspicion as a spy. He ended up in Ruhleben prison camp near Berlin, where British civilian prisoners were housed in a former horse-racing track, six men to a horse stall. Despite the crowded conditions, the prisoners, among them academics and musicians caught in Germany at the outbreak of war, created a thriving culture. Bell taught philosophy and history at Ruhleben Camp School.

From 1914, Harvard worked with the U.S. State Department to bring him to the then-neutral United States, but the warring sides couldn’t agree on prisoner exchanges. Yet living near Berlin turned out to be an advantage for his future career, as he stayed near friends with sensitive positions in German military intelligence.

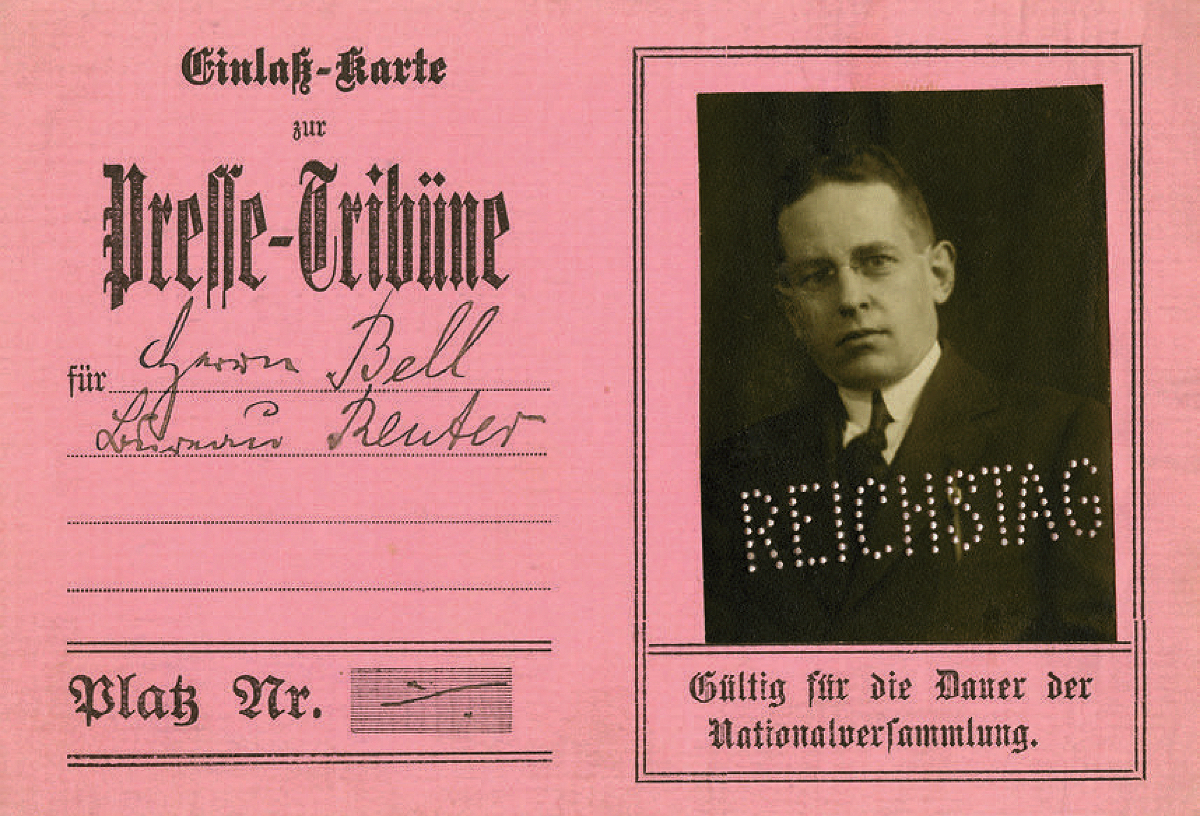

At war’s end, Bell spent weeks in Berlin engaging in conversations with his well-placed sources. Because of those connections and his fluency in German, MI6 hired him as a secret agent in desperate, starving 1919 Germany. Democracy barely survived while a vicious civil war raged between right-wing and communist forces. Evading gunfire, explosions, and assassins, Bell learned that antisemitic forces had finally gained the upper hand. By late 1919, they were the strongest organization in Germany and planned race war.

In Versailles and London, Bell developed a plan to thwart the evil and befriend democratic Germany. Despite support from prominent quarters, influential British politicians blocked his proposal. Some were single-mindedly obsessed with fighting communism, while others worked to block America’s rise to power.

Still, Bell succeeded in showing important people the emerging danger. They included the founder and head of MI6, Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming, and its future World War II chief, Sir Stewart Menzies. Thanks in large part to Bell’s early warning, Britain kept pace with German rearmament during the 1930s. Without him, the Nazis might have won the war.

In 1922, Dr. Bell took up a position as philosophy instructor at Harvard and married Hazel Deinstadt, a fellow Nova Scotian and former war nurse. Owing to prudent investments and careful saving, he retired from teaching and business pursuits before the age of 50. The Bells moved to Chester, Nova Scotia, and a life of service and contemplation.

In 1939, he put his retirement on hold to study the Nazis. He soon cracked their secret plan for racial extermination. Bell sent the revelation to his intelligence contacts, including his Harvard friend Francis Deak, who later served in the U.S. State Department during World War II and was a principal figure in the Pond, predecessor organization of the CIA. Leading Canadian newspaper Saturday Night published Bell’s warnings under the headlines: “Exterminate Non-Germans, Dogma of Mein Kampf” and “Hitler’s Extermination Policy Is Worldwide.”

Bell understood the Nazis meant to kill all non-Aryans, including Jews, Slavs, Blacks, and Asians, everywhere in the world. “Hitler’s European policy,” he wrote in Saturday Night, “is merely the first stage.” His Holocaust warning was the earliest by years. The next appeared in secret intelligence files in 1941 and in the press in 1942. Hitler’s plan required utmost secrecy, but Bell was the first to lift the veil.

After the war, Bell took up reading detective stories. It was a fitting pastime for one of history’s greatest secret detectives.

He died in Chester on April 4, 1965, in his home by the sea.