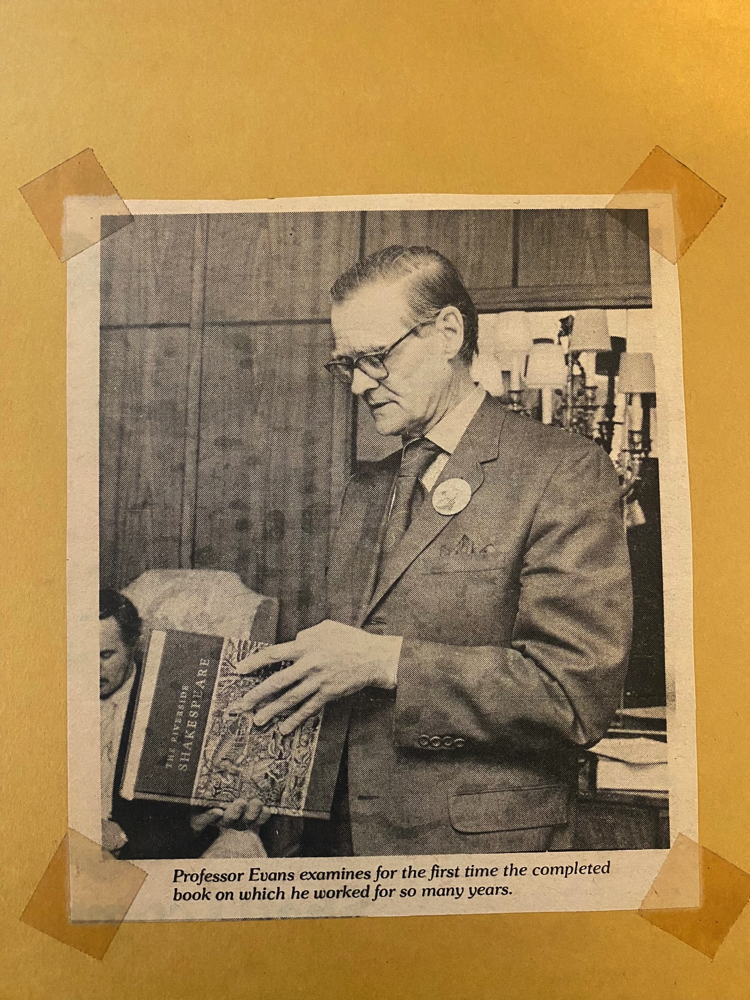

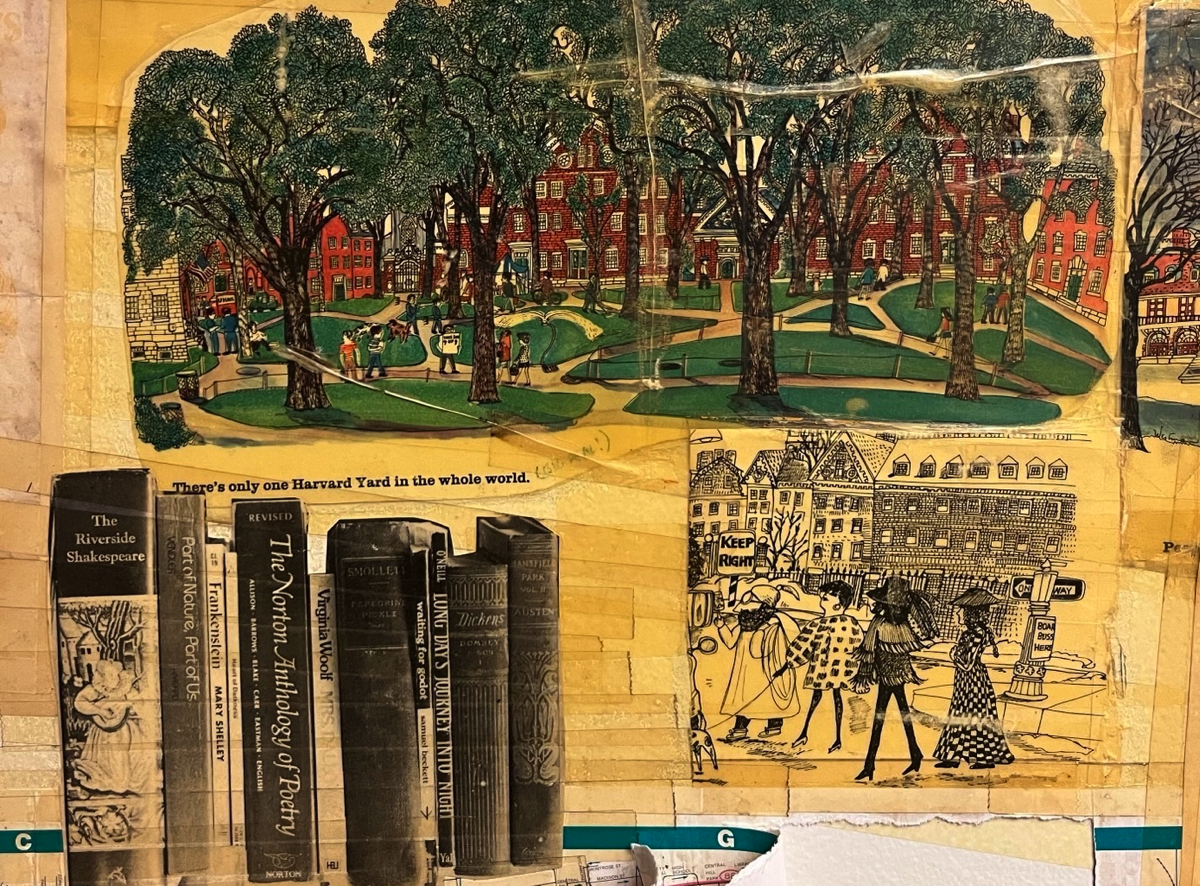

Although I entered Harvard’s graduate program in English in 1974 believing I’d focus my attention on Romantic poetry, I soon gravitated to Widener X, the oddly signified office of Cabot professor of English literature G. Blakemore Evans in the main library. His colleagues referred to him as “Gwynne.” He had just brought out The Riverside Shakespeare, and as common as colossal achievements are at Harvard, this single volume of the complete works, intended mainly for classroom use but also suitable for scholars, was a very big deal in the world of what was then referred to as English and American literature. Among its many distinctions, it was the edition to which the single-volume Harvard Concordance to Shakespeare, also published in 1974 by Marvin Spevack, Ph.D. ’53, was keyed. The pairing was formidable. As a first-year graduate student, I felt privileged to be in the vicinity. When Evans agreed to be my faculty adviser and, later, to direct my dissertation, I was overjoyed.

When I started my teaching career at Davidson College in 1980, I didn’t hesitate to make The Riverside Shakespeare my required text. For the next 43 years, I didn’t deviate from it, and a former student, now teaching at Davidson himself, has been assigning it during his tenure. It is a notoriously big book that students joke about carrying around campus. I think they’re joking; I sense that they’re generally proud of hauling around a tome even bigger than the biggest science text.

A Shakespeare class wouldn’t be complete without at least one student’s Riverside escaping the small classroom desk and crashing to the floor, shooting everyone to attention. In my first year of teaching, loathe to lose face by forfeiting control of that unwieldy volume, I painstakingly cut mine apart, unbinding it so that each play could stand alone. I kept them all in big, red three-ring binders they barely fit, the comedies and histories in volume 1 and the tragedies and romances in volume 2. When I needed to fish out a particular play to teach, I would struggle to open and close those over-sized binders while keeping all of the ring-holes in the right place. I’d put an individual play or two at a time in a much smaller binder that looked rather like a choral music holder. To my students’ initial amazement, I’d call out, “Turn to page 898.” The wonder was written on their faces: how could I have that many pages in that slender binder? Then they saw the trick and envied the convenience. But I didn’t recommend disassembling a book so well put together that it required an entire day to take apart.

Students’ experience of studying Shakespeare with me seems inextricably linked in their memories of The Riverside Shakespeare. When I retired recently, a number of them wrote to me specifically about how they still cherish it. Here’s a sampling.

- “At some point, I actually lugged that six-pound compendium back to Switzerland, where I have lived and worked for the past 20 years. Just for nostalgia” (’83).

- “…looking forward to diving into my Riverside Shakespeare later this week for a fun refresher!” (’88).

- “One of my proudest Dad moments recently was when we were arguing with our two kids over whose specific copy of the Riverside Shakespeare had just been pulled from the shelf to check a reference (one of four separate copies in one household!)” (’90).

- “The Riverside Shakespeare anthology that I got to know so well then has traveled with me everywhere since. (I just pulled it off the shelf now and found three folded notebook pages of handwritten notes about The Tempest.)” (’93).

- “This year I taught The Tempest and Julius Caesar. I so wish I had my old Riverside and notes. Alas, they were swallowed by the sands of time” (’93).

- “I was thinking of you just a few weeks ago as I handed my Riverside Shakespeare to my 15-year-old daughter” (’95).

- “I have carried my Riverside Shakespeare through 13 years and 10 moves since I bought it” (’12).

- “The Riverside anthology has the distinction of being the only textbook I did not sell back at the end of a semester” (’13).

Here’s a mini-comedy on the subject:

I have a confession to make. I have held onto my Riverside Shakespeare for 36 years now. We are about to make a move from Mississippi to Tennessee. As I packed up books, I was reminded of just how heavy that text is. I deliberated and decided to donate it instead of packing it for the move, but I realized my mistake almost immediately and sent my husband to the store to fetch it back for me! (’87).

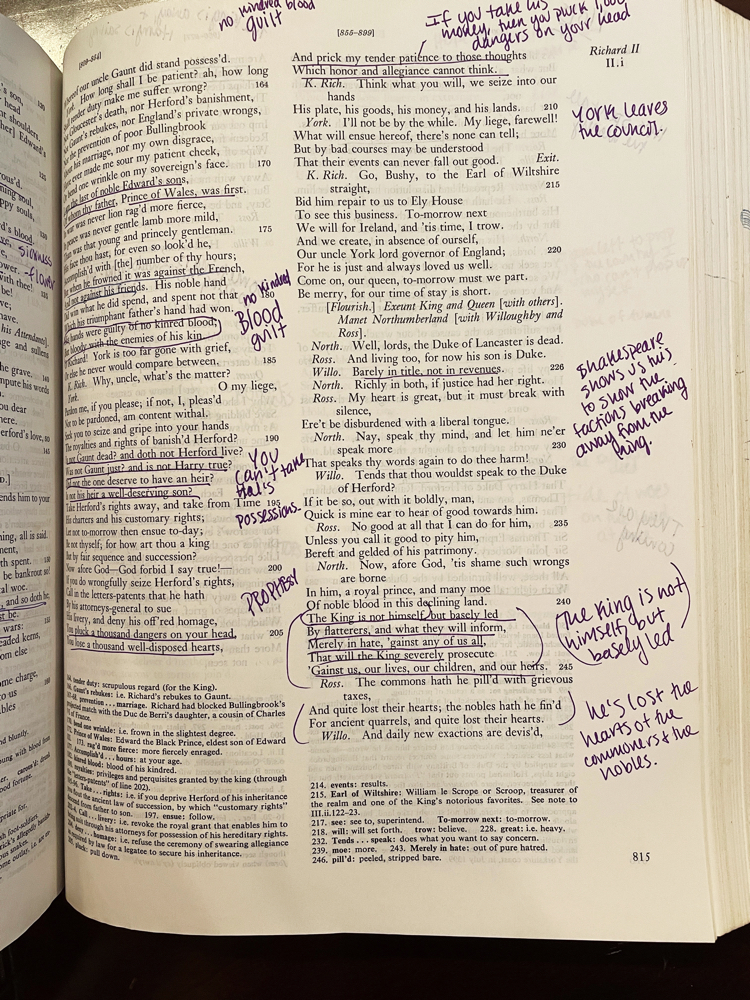

Two former students sent me photographs of a page from their Riverside. Here’s one.

The other one demarcates in pencil Henry V’s speech in 1.2 where he chastises the French ambassador for delivering the Dauphin’s insulting gift of tennis balls. Next to the speech, she has written, “The great reveal.”

Professor Evans was probably aware at the time, as I was not, that our origins ran parallel. For a long while, I ignorantly believed he was a native Welshman. But he was born in Columbus, Ohio, where his father was a German professor at Ohio State University. He graduated from OSU in 1934 and earned his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1940. I was born near Cincinnati, graduated from OSU, then traveled to Harvard for graduate school. This migration from a Big Ten state school to an Ivy League graduate program was relatively rare; most Ivy League Ph.D. programs drew from either other Ivy League institutions or elite four-year colleges, like Williams and Swarthmore. For several years after entering Harvard, I felt a little out of place and sometimes suffered from imposter syndrome. Did the admissions committee realize my B. A. was from Ohio State?

In retrospect, I remember sensing something of a kindred spirit in Evans regarding my humble beginnings. He’d taught at two midwestern public schools—the University of Wisconsin and the University of Illinois—before Harvard snatched him up as Cabot professor in 1967 just in time for him to reflect glory on the University with The Riverside Shakespeare. Did he ever feel the least bit of self-doubt about winding up in Widener X? Whatever the unknowable answer to that question, he was, to me, the least stuffy, most down-to-earth, and most endearingly self-effacing academic I’d ever known. I remember asking him why he and his Anglified colleagues pronounced the title Don Quixote like Don Quick-sot. He responded, wryly, “Well, quixotic.” I also remember expressing anxiety to him over some aspect of my dissertation (probably finishing it on time…or at all), and he reassuringly responded, “You? Worried? You’re a rock.” Although I probably just looked downward in embarrassment, inside I was beaming.

My good fortune at having Evans as an adviser extended to his appointment as director of graduate studies at the time. Harvard doctoral students in English in those years had to prove reading competency in three languages, one of them ancient. I’d had enough French in college to receive a pass for that one, but for the other two I was in trouble. I’d taken some Latin in my senior year of college, but the “innovative” method of teaching it left me incapable of reading actual ancient Latin. I kept failing the reading exams, even though we were allowed to use a dual-language dictionary. The alternative was to take two literature courses in the language—a major drain on time. When I went to Evans with a bargain up my sleeve about receiving Latin credit, I learned that languages had been a challenge for him, too. (I later discovered that his professor father had made him live with a German family to atone for failing his own German exam.) He graciously (and empathetically) agreed to my proposal: if I could earn an A in the second of the two Latin courses required in lieu of passing the reading test, he would let me skip the first course. I managed, barely, to pull out my A. Then on to the last remaining language, Spanish. Same proposal: if I could ace an upper-level class in Spanish drama of the Golden Age, he would accept that one course instead of two lower-level lit courses. Again, with the help of a sympathetic Spanish graduate student, I brought home the golden fleece.

I believe Evans was also a champion of women pursuing graduate degrees. His daughter, Pamela, earned a Ph.D. in 1976 from Northwestern in communication disorders and learning disabilities. Harvard’s graduate program in English had only recently become co-educational in 1974—a shift that disturbed some traditions and traditionalists. The number of academic jobs continued to decline as recessive markets plagued the economy from 1969 to 1980, when I began looking for an appointment. Now women had joined the competition for those rare plums and, as a result, faced no little backlash. In one of the two graduate seminars I took with Evans, a male student sat next to me muttering insults (“What a stupid thing to say” and “You’ve got to be kidding”) that only I could hear as I soldiered through an oral presentation to the cohort. I didn’t have the courage to report him to Evans, who, I now think, would have been intolerant of such behavior. Later, I also came to realize that the student was simply insecure and that I, even with my midwestern upbringing and education, intimidated him.

The seminars I took with Evans—on Shakespeare’s source material and on the age of Dryden—comprised a handful of dedicated souls (even the insult-whisperer) who met weekly in Widener X. This office, just around the corner from the huge, open, sunlit reading room, was more like a suite; each of its two spacious rooms was lined with loaded bookshelves and housed its own mammoth desk. The room we used for seminar meetings could accommodate about eight chairs for students, arranged haphazardly, wherever they would fit. Both rooms smelled of leather bindings and old wood. Oak, mahogany, and walnut cast a dark hue. The rooms were cluttered with papers, stray books, and large envelopes I was sure contained solicitations for the professor’s attention. Its disarray was utterly beautiful, inspiring, and fantastical. This was where The Riverside Shakespeare was put together in final form. It evoked the wonder that Prince Ferdinand feels about Prospero’s enchanted island when he says, “Let me live here ever.”

For the most part, The Riverside Shakespeare did not disappoint its expectant audience. Reviewers in high places effused. “The precision and abundance of the textual notes, together with the sound and consistent choices of the editor in establishing the text, compare favourably with the best multi-volume editions,” wrote J. M. Maguin, professor at University Paul Valéry Montpellier, in Cahiers élisabéthains. “This makes the Riverside Shakespeare the new standard edition the publishers claim it to be.” Writing for Shakespeare Quarterly, William C. McAvoy, English professor at St. Louis University, opened with this glowing pronouncement: “Let it be said at the very outset that Professor G. Blakemore Evans has in The Riverside Shakespeare produced what is textually the best edition of Shakespeare yet to appear.” Apparently, however, the image of the Elizabethan valance that encircled the first edition’s cover struck more than one reviewer as unfortunate. “The reviewer must confess an allergy to the cover selected,” wrote Maguin. “The…valance…makes a horribly sickly combination with the chocolate brown of the binding. Could not a book so lavishly and tastefully illustrated inside afford a plain, homely, decent cloth cover?”

Stephen Booth, reviewing the edition for the New York Review of Books, was equally offended by the book’s cover but less charitable even than Maguin. The UC Berkeley professor and distinguished scholar of Shakespeare’s sonnets wrote in the review’s lengthy second paragraph that “The one-volume Riverside Shakespeare is a big ugly book. The cover is shiny chocolate in color and has a stripe of picture around it….It may be a good reproduction of a very ugly valance.”

But Booth is just warming up. His vilification almost seems ad hominem at times; my admiration of Booth from afar notwithstanding, his animosity toward Evans and the work makes me wonder what might have been going on behind the scenes. “This edition fails,” Booth intones, “because, from its opening pages onward, its concerns are usually different from, inconsistent with, and invidious to the concerns of those who will read it.” From the publisher’s preface to the explanatory apparatus to the failure to proofread the whole work perfectly, Booth slashes through every conceivable aspect of The Riverside Shakespeare. He objects to the ranking within the list of editors that appears to place Harvard contributors above others. He finds information about textual variants too granular. He accuses the edition of being “generally secretive”—that is, difficult for the reader to find anything. He spends a large portion of the review defending his preference for The Pelican Shakespeare over The Riverside. Through a near fetishist’s lens, he commends the Pelican, which “weighs five-and-a-quarter pounds and costs $12.95” above the Riverside, which “weighs six-and-three-eighths pounds and costs $14.95.” (Those were the days!) Everyone has a favorite edition that is loved as much for nostalgic reasons as for reason itself, as a beloved stuffed animal is believed irreplaceable. But Booth’s resolve to “stick with The Pelican Shakespeare” is almost cultish.

The single positive element of The Riverside for Booth is Harry Levin’s General Introduction, in Booth’s estimation “so perfectly non-narcissistic.” (This verdict is despite Levin’s position as Babbitt professor of comparative literature at Harvard.) He wishes the whole edition were as accessible and reader-friendly, but, alas, he says, it is aimed at pedants. His praise emboldened Levin to write a response to Booth in the next edition of NYRB, in which he parries Booth’s complaints about the book with measured counterarguments inflected with correction. “When Professor Booth speaks of [textual] ‘variations,’ where presumably he means ‘variants,’” scolds Levin, “he reveals a technical naïveté.” Booth’s terse response to Levin’s letter sustains the invective, but with passive aggression:

I am grateful for the opportunity to respond to Professor Levin’s letter.

To do so, however, might unreasonably dignify the logic of his particular arguments and might just as unreasonably tend to obscure his generosity in trying to find some. The letter is an admirable gesture of loyalty and is best let stand as such.

No other text I used for teaching spanned my entire career in quite the same way as this one. Perhaps only those of us who spend untold hours poring over the same edition of a text have the experience of virtually memorizing its contours, as well as its contents. The Riverside has a distinct advantage in this arena. Unlike other classroom staples—for instance, the Norton anthologies, which come out in new editions every few years—the Riverside has undergone only a second edition, and although the page numbers are different in the second edition, the page layout is exactly the same, meaning that I can still use my disassembled first edition just by writing in a new page number in the lower corner of each page.

Rereading Twelfth Night, I anticipate the moment in 1.5 when Viola, disguised as a boy, speaks in her own voice to Olivia, whom she’s trying to woo for Duke Orsino. Until now, she’s been relying on courtly love clichés, but when Olivia asks her how she herself would woo, she spellbinds Olivia with her poetry. I would, she says,

make the babbling gossip of the air

Cry out “Olivia!” O, you should not rest

Between the elements of air and earth

But you should pity me!

Addressing Olivia by name, Viola causes the countess, inconveniently, to fall for a woman disguised as a boy. I know exactly where that speech, which I long ago learned by heart and must always recite in class, lies on the page in 1.5, just as I know that nearly the entirety of the next scene I’ll relish, 2.2, fits into the right column of its page.

There, the clever Viola figures out that Olivia is smitten by her, disguise and all. In her comic soliloquy, another speech I cannot bear to leave without reading aloud, Viola resolves not to act on the dilemma she’s created. “O, time, thou must untangle it, not I, / It is too hard a knot for me to untie.” Thus the play now has another three acts to work out its gender and love complications.

Years of notetaking in the plays’ margins accumulate into concepts that inform over-arching readings. Atop many pages of Measure for Measure appear the words “No remedy” in light pencil, signaling their appearance on those pages. None of the characters can figure out a “remedy” for preventing Claudio’s execution—an overly severe punishment, enacted by a stringent substitute for the absent duke, for Claudio’s premarital sex with his fiancée, resulting in her pregnancy. Then the actual duke, Vincentio, returns to Vienna and figures out a “remedy,” albeit one as extreme as the deputy’s punishment, for saving Claudio’s life. The words “fashion” from Much Ado about Nothing, “mock” from Henry V, and “show” from The Merchant of Venice all transcend their simplicity and gather meaning in numbers, each instance penciled in, over and over on page after page.

Year after year, I puzzle anew through the footnotes explaining Mercutio’s famed Queen Mab speech in 1.4 of Romeo and Juliet. Understanding never comes easily, but the notes carefully, gradually, clarify the meaning. The same goes for the debate over invading France in Henry V, 1.2, including the heady reasoning involving the Salic law. Here again, the constancy of this edition, its reliability over time, makes it timeless. The individual plays’ introductions, though now 50 years old, remain classic essays for beginners and returning students alike, orienting all of us to texts we’re about to discover or rediscover. True, the literary theory movement has bypassed those introductory essays, making them seem naïve to today’s scholar, but for sheer good sense, intellectual stimulation, and elegant writing, they endure. I’ve never read better introductions to some of the comedies than Anne Barton’s. I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised that Stephen Booth singles out hers as feeble in his review and extols the ones written by, in my opinion, the least dazzling of the four introducers.

G. Blakemore Evans became emeritus in 1982 and passed away in 2005, at 93. Before that time, I had visited him and his wife, Florence (“Betty”), once or twice in their apartment on Memorial Drive in Cambridge. They were married for 62 years. Evans was also survived by a son, Michael B. Evans, and the aforementioned daughter, Pamela G. Hook, who remembers that her mother helped proofread the entire Riverside text. “She was a voracious reader,” says Pamela, “and considered it an opportunity to read the plays with my father (even every punctuation mark).”