Tributes to trees, in form and metaphor, have appeared in art, music and poetry for millennia. “And this our life, exempt from public haunt,/Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,/Sermons in stones, and good in everything,” wrote Shakespeare. Trees of knowledge and trees of life have deep taproots in human culture. And if trees really had tongues, they might tell the story sketched in the prefatory chapters of Smithsonian Trees of North America: of dwindling habitats, precipitous climate shifts, and even extinction.

The book is the work of a decade by W. John Kress ’73, distinguished scientist and curator emeritus of botany at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Now living in Vermont, he spent most of his career studying plants of the tropics. But in the early 2000s, he began thinking about putting together a book about North American trees. He was well begun on the project, crisscrossing the continent to photograph the last of the 326 common native and introduced tree species featured in the book, when COVID restricted travel. To overcome the lockdown, he writes in the acknowledgements, he turned for help to botanical colleagues across the map, who sent him specimens by overnight mail to photograph in his home studio.

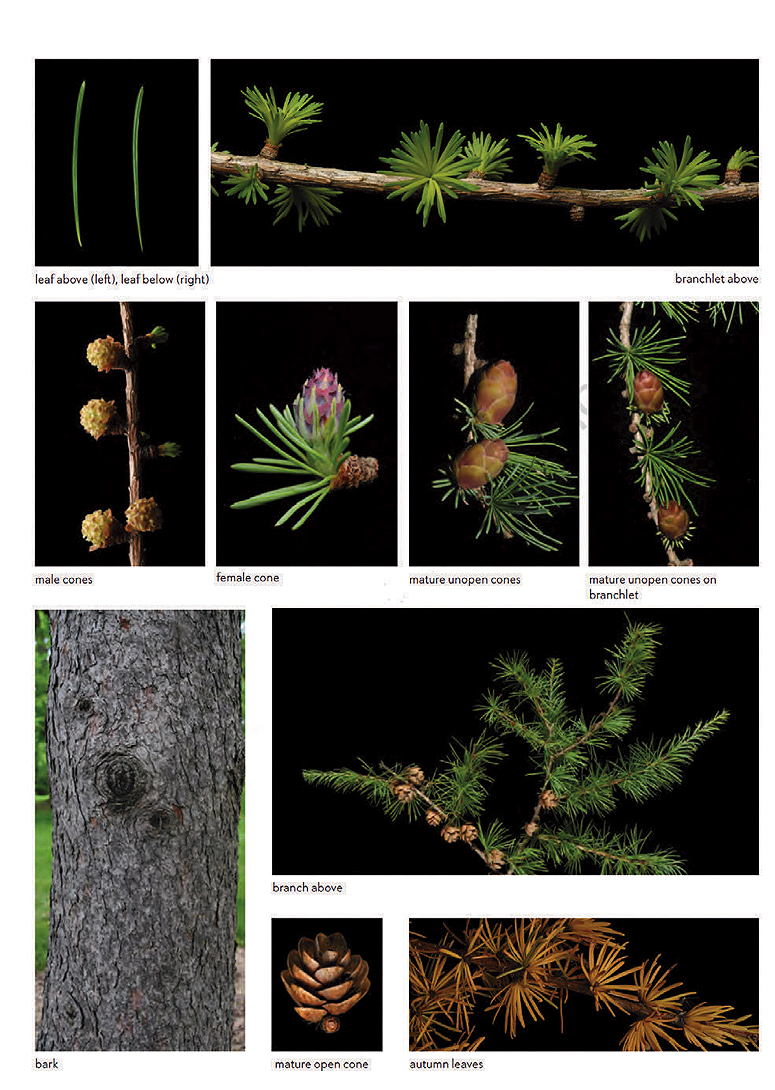

The result is stunning. The photographs, silhouetted against a rich, black background, elevate tree fruits and flowers, buds and branches, leaves and seeds to an art form that rivals any other. Together with the detailed descriptions of each species, they aid in the identification of the common trees of the North American continent. Many of the images were originally assembled during the author’s work on a free tree identification app for smartphones called Leafsnap (no longer available; Kress instead recommends iNaturalist, a crowdsourced alternative for identifying plants, animals, insects and fungi). But this beautiful book is not intended as a field guide—or, at least, not in its 800-page physical manifestation, which weighs a hefty six and a quarter pounds (for portability, consider a second copy in one of the digital formats that will be available upon publication). Instead, Kress hopes that the book will encourage readers to identify with trees.

Each species entry, listed in order from oldest to most recently evolved, includes abundant photographs, Latin and common names, a range map, a physical description, a discussion of its uses and value, ecology, vulnerability to climate change, and conservation status. What sets Kress’s book apart from existing field guides is that the photographs have been taken, chosen, and presented with an eye for morphological difference—critical for distinguishing related species. Still, identifying trees can be complicated. Kress introduces readers to leaf shapes, structure, and orientation; to the appearance of bark and wood grain; and to the diversity of cones, flowers and fruits. Leaves are the best first clue, but as he acknowledges, a consequence of evolution is natural variation that can sometimes be misleading. Fruits and seeds—“the glue that holds forest communities together”—aid identification, too, but learning about their variation can be “overwhelming.” The number of seeds makes the difference between a drupe (one) and a berry (many), for example, but what distinguishes a pome from a follicle, nut, samara, or capsule? Kress helpfully compares these types of fruits by setting photographs of each form side-by-side on a full page, as he does for cones, and for flowers and inflorescences, too.

Kress, who won the 2021 Sargent Award from Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum to support his research for the book, wrote it for three reasons, as he explains in the preface. Foremost, he believes that acquainting people with the names of the trees they encounter will enrich their lives. Identifying the species is an initial step.

His remaining aspirations perhaps reflect his training as an ecologist. First, he answers the question: What do trees do for humans? He hopes to “instill in readers a sense of the value of trees” to them personally, and to make plain trees’ role in maintaining the health of forest communities, ecosystems, and the planet generally. In the foreword, conservation biologist Margaret D. Lowman enumerates their many virtues. Besides housing an estimated half of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity, trees provide “medicines, foods, timber, shade, climate change amelioration, soil conservation, oxygen, energy production, and a spiritual heritage,” she writes, “for over two billion people on earth who practice religions that seek sanctuary in forests.”

If recognizing the ecological benefits that trees provide humans is one facet of a two-way relationship, the other is human understanding of what trees need to survive. This is his final impetus, Kress says, for writing the book. With exceptional clarity and authority, he outlines the case for conservation, and provides a basic introduction to tree morphology and ecology. The explicit subtext of the complex diversity in tree reproductive strategies (human sexual activity is humdrum compared to tree sex and asexual reproduction) is that many tree species, and the ecosystems they support, are vulnerable to human environmental interventions.

Kress delves briefly into the nature of this vulnerability. While there are an estimated three trillion stems (individual trees) globally—half as many as before the dawn of agriculture between 10,000 and 12,000 years ago—a small number of species accounts for most. In the Amazon, for instance, 1.4 percent of species account for half the trees. “It is astounding to think that the other 98.6 percent of the tree species in the Amazon are mostly rare,” he writes. “Many have not yet been discovered or described by botanists.” Astoundingly, an estimated 15 billion trees are lost each year, Kress reports. The principal threats are loss of habitat; commercial exploitation; environmental pollution; urbanization; invasive species; and the spread of animal and plant diseases and pests.

Although the scientific case for forest conservation is compelling—a natural woodland, with its intricate web of plant diversity, for example, sequesters as much as 40 times the carbon of an equivalent area of tree plantation (see “Plants on a Changing Planet,” May-June 2024, page 38)—cultivating a deeper human connection to trees involves more than facts. And that is what Kress seeks to achieve with Smithsonian Trees of North America in photographs and words. Peppering the introductory chapters are references drawn from popular culture—the song “Hickory Wind,” co-written by Gram Parsons ’67 (see “Sound as Ever,” July-August 2023, page 44); a poem about poplars by Gerard Manley Hopkins—and reflections on what it means to get to know a tree. Chapter five, on tree names and identification, begins with a quote that neatly sums one of the book’s principal aims: “To know a tree’s name is the beginning of an acquaintance—not an end in itself,” writes Julia Ellen Rogers in The Tree Book. “There is all the rest of one’s life in which to follow it up. Tree friendships are very precious things.”