The life of Lawrence S. Bacow, Harvard’s twenty-ninth president, has been shadowed and shaped by the Holocaust. His mother, Ruth Wertheim, survived Auschwitz and, as he has related, arrived in the United States on the second Liberty Ship that brought refugees from Europe. Her experiences as a refugee (at one point being denied entry into France) informed some of his decisions as the University’s leader. As he told the Harvard Gazette in a May 2023 interview reviewing his presidency:

I didn’t know that in my second year, we’d have a freshman who would be turned away at the border—at Logan Airport — basically because of his ethnicity. That offended me, so we went to bat for Ismail Ajjawi. I never anticipated…after we announced we were going to continue to be all remote in the fall [as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic], the federal government would announce that any foreign student at an institution that was teaching remotely had to leave the country. I was greatly disturbed by that.

The latter action prompted Bacow to organize a lawsuit by Harvard and MIT that resulted in reversing the federal order.

In a personal, rather than an official, capacity, he traveled to Londorf, Germany, on September 14, 2022, to speak at the dedication of a memorial to the Jews of Londorf, who were transported to concentration camps on that date in 1942. On that wrenching occasion, he said:

Thank you, citizens and residents, for acknowledging the Jews of Londorf, for recognizing the injustice and inhumanity to which they were subjected in life.

It is never too late to do right, and I appreciate the kindness that this effort represents. Thank you for this mitzvah—Hebrew for “good deed.”

I stand before you—together with my sister—together with my children—as the descendants of the only survivor among those taken from this town—taken from their homes 80 years ago today.

My mother, Ruth Wertheim, was transported to Theresienstadt along with her parents, Leopold and Emma, and her grandfather, David. Her sister, Inge, had already been arrested. My mother was 15.

My mother’s family all perished in Auschwitz. They were among six million Jews murdered.

Six million is a number beyond understanding.

So, here I am, one man. My sister, one woman. My sister’s children and my children have children of their own.

The sweetness of life cannot be put into words.

The bitterness of life can.…

It is one thing to recognize the dead, one thing to place a plaque in their memory. It is another thing—more important and more difficult—to speak up for the living.

May each of us pledge—here, today—to do the mitzvah—the good deed—of raising a moral voice in response to bigotry, hatred, and injustice, not just where we live but everywhere. May we give voice to those to those whose voices have been silenced; to those who may appear different from the majority.

If we are successful, we will spare future generations the sad task of holding ceremonies like this one. We will create more opportunities for more people to do mitzvot—good deeds. And we will remember the power that lies within each and every one of us to do right.

But he had never brought himself to visit one of the death camps. When the University asked him to represent Harvard at the ceremony observing the eightieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and Birkenau this January 27, Bacow agreed—knowing that the date was especially resonant for him as the anniversary of his mother’s death, in 1994. He attended with his wife, Adele Fleet Bacow.

Appropriately, at the event, the speakers were survivors of the death camps; the world leaders in the audience were silent witnesses to their testimony.

President Bacow wrote these reflections at Harvard Magazine’s request.

—The Editors

People were drawn to my mother. In my family, she was everyone’s favorite aunt. Growing up, my friends always wanted to play at my house because she made them feel so welcome. She was warm and compassionate, cheerful and fun, positive and optimistic. Everyone loved her.

Less visible and less known was my mother’s extraordinary strength and resilience. Born and raised in Germany, she was deported to Theresienstadt, a concentration camp in what is now the Czech Republic, on September 14, 1942, at the age of 15, along with her family and the other 120 Jews from her town. Three years later, she would be the only one to return alive. She survived the horrors of Auschwitz, where more than one million Jews were murdered. She lost her mother, her father, and her sister. She lost her family and friends. She lost her community.

I once asked my mother how she could have lived through such trauma and still seem so normal. Her response:

By the age of 18, Hitler had taken away from me everyone and everything that I loved—my family, my friends, my home, and my youth. I realized if I remained bitter and angry, he would also destroy the rest of my life. Living well would be my revenge.

January 27 marked the eightieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. Harvard was invited to send a delegate to the commemoration, and, knowing my family’s history, President Garber asked if Adele and I would represent the University. Though I had avoided visiting any of the death camps previously, we agreed to make the trip. We were hosted by Harvard Law School alums who were wonderfully sensitive and attentive: Agata Mazurowska-Rozdeiczer, President of the Harvard Club of Poland, and her husband, Lukasz Rozdeiczer, Executive Vice President of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation.

Saturday, January 25–Private Tour

Even though my mother had described her time at Auschwitz in some detail, Adele and I were still unprepared for what we saw.

Auschwitz is immense. Upon entering, one encounters barracks almost as far as the eye can see, flimsy wooden structures with dirt floors, in many cases former stables. Here, my mother and tens of thousands of other prisoners were housed with little food, less heat, and only a latrine for sanitary facilities. Despite attempts by the Nazis to destroy them completely before the end of the war, the remnants of the gas chambers and crematoria are also still visible. The Nazis designed Auschwitz for only one purpose: to murder people as quickly and efficiently as possible. To put the scale of the place in context, 2,977 people died on 9/11. By contrast, more than one million Jews were murdered in Auschwitz.

In 1944, my mother and her family were jammed into a cattle car with others from Theresienstadt for the trip to Auschwitz. With no food or water available, many did not survive the trip. Those who did emerged onto a large platform. A Nazi officer separated those who could work from those who could not, the sturdy from the frail, the young from the old. Since most prisoners were already emaciated from detention in other concentration camps, about 80 percent of those who were transported to Auschwitz were sent immediately to the gas chambers.

As Adele and I stood on the same platform, the gas chambers and crematoria were visible to us just as they had been to my mother and all other deportees arriving at Auschwitz. We recalled her description of being separated from her parents, the heartbreak of knowing that she would never see them again. If you closed your eyes, you could imagine the desperation: the cries of the families being separated, the smoke rising from the crematoria, and the stench of burning flesh that my mother said constantly hung over the camp. I kept thinking not only of my mother who survived, but those who did not, especially the young children who immediately went to their deaths upon arrival—all 250,000 of them. Both Adele and I were overcome by emotion.

Auschwitz has been preserved for posterity as a museum. A few of the buildings now contain exhibits that document the indescribable cruelty of the Nazis. Those who were marched off to the gas chambers were first stripped naked and had their heads shaved. We saw a room filled with human hair; we saw the ponytails and the pigtails of children. Another room was filled with nothing but thousands of pairs of children’s shoes. Another room was filled with images of those who were gassed, their faces and their names preserved. The Nazis were meticulous record keepers. They photographed their victims before murdering them.

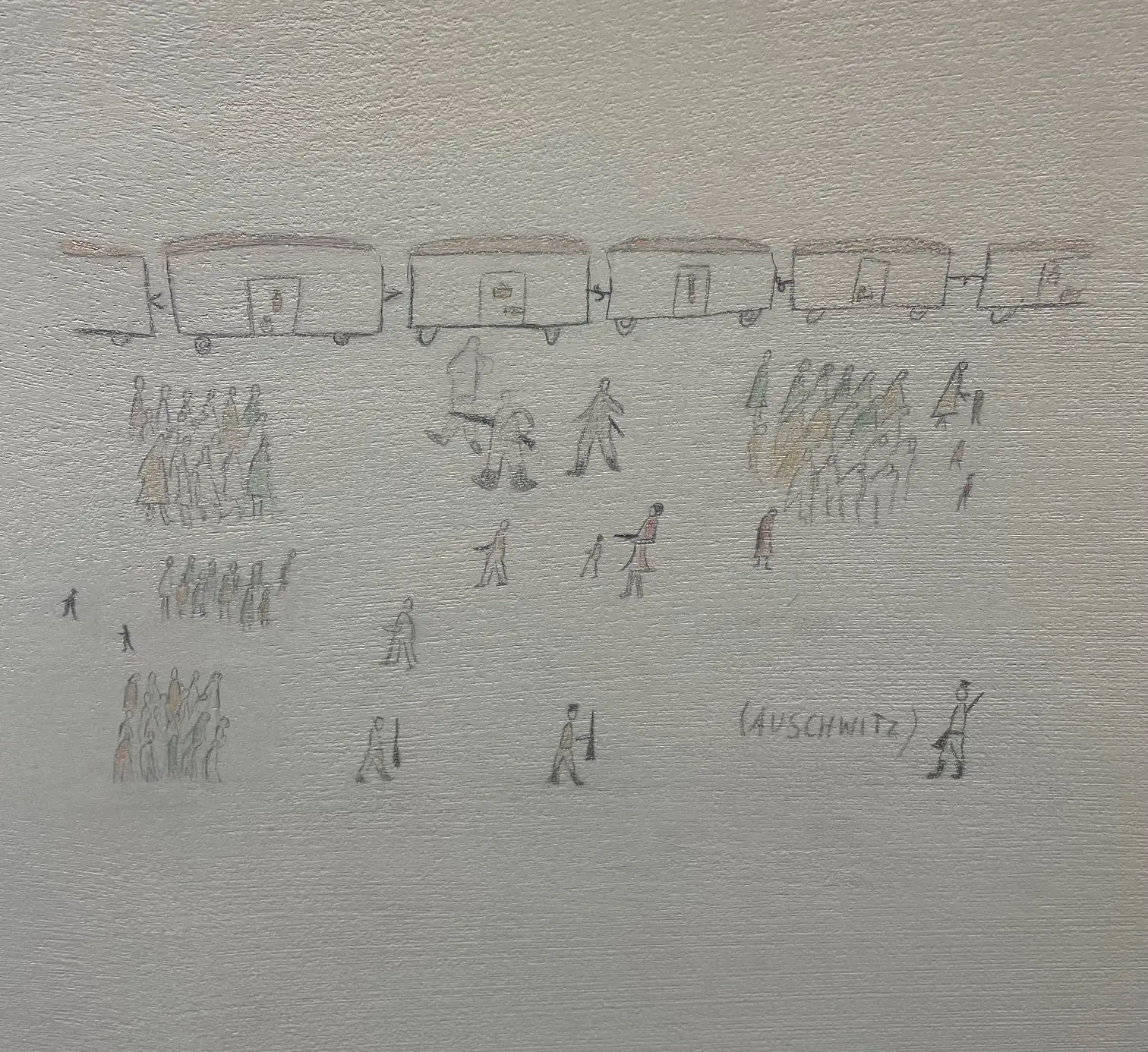

One of the most powerful exhibits was by an Israeli artist, Michal Rovner. She reproduced drawings made by children of their experience in the Warsaw Ghetto, Theresienstadt, and other camps. Seeing the horrors of these places through the eyes of these young artists—drawings of cattle cars, families being separated, bodies carried on stretchers—was devastating. Sights no child should ever have to witness, let alone document.

Our tour of Auschwitz ended with a visit to the Book of Names, where the six million victims of the Holocaust are recorded. I searched and found the names of my family: my grandfather, Leopold Wertheim, for whom I am named; my grandmother, Emma Wertheim; and my aunt, Ingeborg Wertheim. Like all of the six million, they have no graves, they have no headstones, but they are not forgotten. They are in the Book of Names.

Monday, January 27—Commemoration Ceremony

After passing through security, we boarded crowded shuttle buses for the short ride to the event. As we entered the venue, a large tent constructed over the entrance of Auschwitz-Birkenau, our first sight was a cattle car used to transport deportees. I suspect I was not alone in contrasting how we had arrived at Auschwitz with how those who we were gathering to remember did. [Late in Bacow’s presidency, a replica Holocaust train car was displayed in Harvard Yard, as part of a nationally touring “Hate Ends Now” exhibition.]

Some two dozen heads of state attended the ceremony, including King Charles of Great Britain, the King and Queen of Spain, President Macron of France, Chancellor Scholz of Germany, President Zelensky of Ukraine, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada, and many others. None of them spoke. They were there, like the rest of us, to bear witness to the survivors.

As each survivor entered the tent, those assembled rose and applauded. Most survivors were in their mid- to late-90s, and quite frail. Many used walkers, canes, or other assistance as they slowly made their way to their seats. There were about 50 in total, down from the 300 who attended the seventy-fifth anniversary ceremony five years ago. Five survivors spoke along with Ronald Lauder, the head of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial Foundation, and Piotr Cywinski, the head of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

Their age and frailty only added to the power of their testimony. Each survivor painted a raw, vivid picture of his or her personal tragedy of Auschwitz—the death of family, the horrendous conditions in the camp, the cruelty of captors, and the combination of luck, determination, and strength of spirit that enabled survival. They talked with pride about their children and grandchildren, and the lives they made for themselves after the war. But, perhaps most importantly, they spoke passionately about the dangers ahead. The rise of antisemitism worldwide was on everyone’s mind. As one speaker said, “we cannot let our past become our children’s future.” As I listened to their remarks, I kept looking over to the heads of state, hoping that they, too, were listening intently. As Elie Wiesel once said, “the opposite of love is not hate. It is indifference.” The world right now cannot afford indifference.

At the end of the ceremony, clergy were invited to come forward to lead in prayer. Many denominations were represented. Jews often mark major ritual events by sounding a ram’s horn, a shofar, and so it was at Auschwitz. Following a number of prayers in English and Polish, a group of rabbis led in the recitation of Kaddish, a prayer that Jews recite in memory of loved ones. Observant Jews recite it daily for 11 months in the year following a death and then every year on the anniversary of the loved one’s death.

Adele and I stood and said the prayer together, not only in commemoration of those many who were murdered at Auschwitz but also for my mother, Ruth Bacow. January 27 is the day she died. Saying Kaddish for her at the place where the ashes of her mother, father, and sister are scattered is something that will stay with me for the rest of my life. I am proud to have represented Harvard—and our community—at this solemn ceremony.