In the wake of the Israel-Palestine protests during the 2023-2024 academic year—especially the pro-Palestinian encampment in Harvard Yard during April and May—the University faced further challenges pertaining to its opaque and seemingly inconsistent disciplinary proceedings. Today, an ad hoc committee to review the College and Graduate School Administrative Boards recommended to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) that:

• ladder faculty members become much more directly involved in and knowledgeable about undergraduate discipline;

• appeals of disciplinary sanctions be modified so they are handled by people more deeply familiar with the disciplinary process; and

• FAS train members of the disciplinary bodies more consistently and educate the faculty at large about their work.

Together, these proposals represent reforms of the disciplinary structure and processes (which are under the faculty’s supervision), but not a blueprint for a wholesale restructuring.

The committee’s work was not focused on the disciplinary morass arising from the events of last spring, but obviously took place in that context. Its report reaches the faculty just one week after Columbia University, under severe pressure from the Trump administration, made adjustments in how its disciplinary process reports to the senior university administration, among other measures.

The committee deferred considering a Harvard Undergraduate Association suggestion that students participate in the disciplinary process. Nor did it address whether or how disciplinary decisions might be more descriptively communicated to a wider University audience for educational purposes.

Its report is on the agenda for the FAS faculty meeting for an in camera discussion next Tuesday, April 1, but none of the recommendations entail legislation, so they may be adopted as FAS Dean Hopi Hoekstra and the Administrative Boards think appropriate. In a letter to the chair dated March 28, Hoekstra hailed the committee’s work for providing “a clear path forward for strengthening these vital boards” and endorsed its recommendations (see below for specific measures).

Given the complex matrix of College and Graduate School disciplinary bodies and processes, which the ad hoc committee accepts as its starting point, its report made two overarching observations pertinent to the challenges of upholding norms of conduct and standards for behavior.

• Disciplinary culture. The committee recommended that the College and Graduate School Ad Boards “continue to adhere to the general principles of assessing individual student behavior and of focusing on the behavior itself without regard to the content of accompanying speech and without trying to assess the merits of the motivations for that behavior” (emphasis added). As a matter of approach or philosophy, in other words, “even when disciplinary measures are imposed, the primary purpose of college discipline is pedagogical and restorative” (emphasis added).

The ad hoc committee report quotes the 2009 review of the Ad Board, to the effect that “except in the rarest of circumstances, students involved in disciplinary cases ultimately will graduate from Harvard; thus the imperative is to help students understand the rules and the consequences of their actions so that they can learn greater responsibility within the College, the University, and beyond.” In other words, Ad Board discipline is not a “criminal justice,” focused on punishment and legalisms.

• The speech and protest challenge. Second, and pertinent to the context of the ad hoc committee’s work, it observes, “[I]n the aftermath of the campus protests of 1969, and continuing up to summer 2024, efforts have been made to develop alternative means for handling cases of expressive speech or political protest. The failure of earlier efforts suggests that this is an ongoing problem.”

Within a community committed to sustaining the conditions for academic freedom and to free speech, in other words, it is particularly challenging to balance rules on permissible protests (so-called time, place, and manner regulations) with speech, or to protect speech while defining hate speech or speech that invites or incites harm to others or constrains other community members’ speech rights.

And that matter of principle is complicated by a logistical problem. “From time to time,” the ad hoc committee report notes, the College Ad Board “faces a cluster of cases that tax its capacity to handle cases” during its routinely scheduled meetings, Moreover, “Especially complex are those cases that reach the [Ad Board] shortly before Commencement,” because students with a pending disciplinary case are not in “good standing” and may not receive their degrees.

That, of course, describes the perfect storm that crashed into the College and Graduate School disciplinary machinery last spring: a cluster of cases, taxing the Ad Boards’ capacity, on difficult issues concerning protest and speech—and falling, as protests often do, in the spring semester shortly before Commencement.

The Context and Committee Charge

To summarize matters briefly: following the Harvard Yard encampment that ended last May 14, 13 undergraduates were suspended or placed on probation by the College Administrative Board, thus becoming ineligible to graduate. The FAS voted the Monday before Commencement to overturn the Ad Board ruling. The Corporation two days later found that those punished had not been restored to good standing, and so could not receive their degrees. Commencement proceeded the next morning, May 23, but protestors and their sympathizers (students and faculty members) walked out. And finally, following student appeals to FAS’s Faculty Council (an elected group of FAS members who advise the dean and prepare Faculty Meeting agendas), the suspensions were reduced to probations, other probations were shortened—and 11 of the undergraduates got their degrees two months late. (For a blow-by blow recapitulation, see “Locked In,” July-August 2024; for further reporting and an analysis of disciplinary challenges from 1969 to today, see “Own Goals,” September-October 2024.)

More important than the chronology was the collateral damage: people outraged by the mildness or severity of the punishments; reliance on the protestors themselves for information about the outcome of the disciplinary process (since the College, Graduate School, and University provided no information); and obvious confusion within FAS itself about its disciplinary standards and processes, and disagreement about both.

Although the University acted during the summer to clarify and unify processes for protests involving more than one school, and restated the rules for protests twice before the semester began, discipline resides principally in the FAS and the professional schools. Hence Dean Hoekstra ‘s October 29 commissioning of the ad hoc committee to review the College and Graduate School Administrative Boards (the last comprehensive review occurred in 2009). She charged it with:

• reviewing the composition of the boards, including the terms of members’ service;

• reviewing the boards’ processes of determining whether rules have been violated and, if so, what sanctions should apply;

• evaluating the sanctions applied, and the consistency of their application;

• reviewing the mechanism for bringing appeals from Ad Board decisions;

• considering the definition of whether students are in “good standing” and its practical implications for fellowships, participation in academic or extracurricular activities, and so on; and

• developing recommendations for educating students, faculty members, and administrators about the work of the Ad Boards.

None of this suggested a wholesale redesign of disciplinary mechanisms stretching back to nineteenth-century Harvard. But the committee’s brief was nonetheless broad.

Hoekstra entrusted this necessary, if perhaps thankless, work to Pforzheimer University Professor Ann Blair (chair); professor of astronomy Edo Berger; Knafel professor of music Suzie Clark; Pierce professor of psychology Matthew Nock; Diston professor of music Anne Shreffler; Baird professor of history Daniel Smail; director of admissions Joy St. John; and professor of organismic and evolutionary biology John Wakeley.

Discipline at Harvard: A Roadmap

The committee’s work and report performs the incredibly useful service of providing a coherent guide to a complicated set of entities and processes. The underlying research involved the committee’s historical and other inquiries, and broad consultation with the Ad Boards, College and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences [GSAS] deans, faculty members who served as personal advisers to students appearing before the boards, resident deans, faculty deans, students who have appeared before the boards, and others. (Because the entities and processes are so little understood, they are summarized here, from the committee’s report.)

Professor Blair (who is a past member of the Harvard Magazine Inc. Board of Directors) said in a conversation about the committee’s work, “We discovered how little we…knew about how the Ad Boards worked”—itself a fair statement of the problem, given that the Boards operate on FAS’s behalf, upholding the faculty’s rules.

To simplify matters, the committee confined its work to the handling of social misconduct (excluding cases of academic misconduct). Even so, it helps to have a navigational aid. The report accordingly focuses on:

the Disciplinary Committee of the Harvard College Ad Board (DCAB), excluding the Petitions Committee (which hears student petitions of academic policy exceptions, such as exam delays or course registration issues) and the Honor Council (which hears cases of academic dishonesty); and

the social misconduct cases heard by the GSAS Ad Board (which hears academic misconduct cases as well).

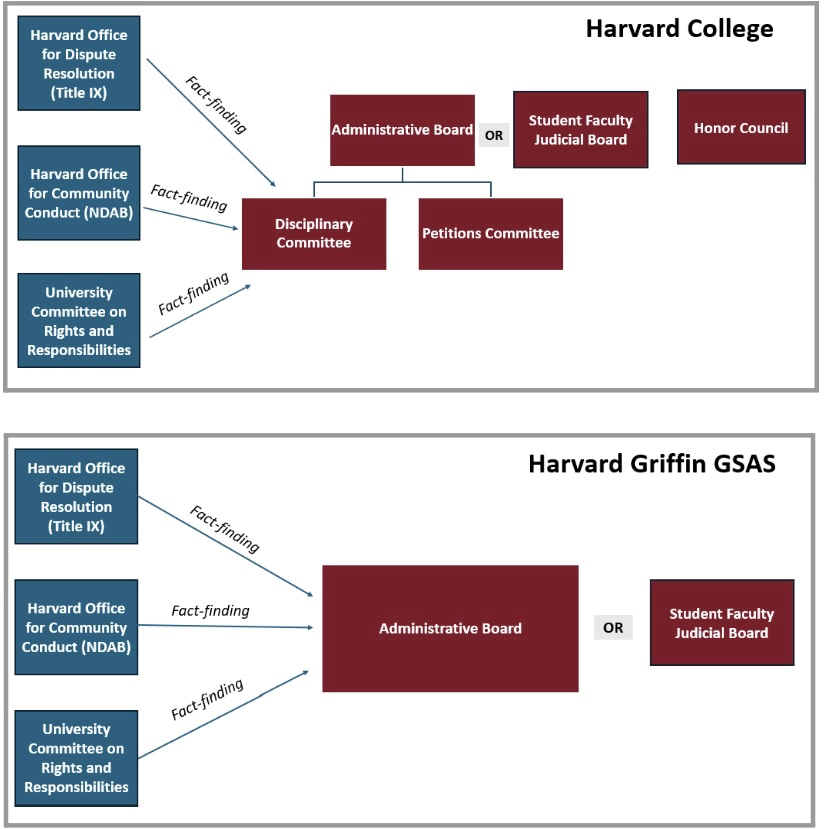

The report documents an alphabet soup of acronyms, covering the entities responsible for investigating sexual assault and gender equity (Title IX) complaints, both under the Office for Gender Equity; the College Honor Council and DCAB, both under the Office of Academic Integrity and Student Conduct (OAISC); and the University Office for Community Conduct (OCC), which administers the Non-discrimination and Anti-bullying (NDAB) policies. (As previously reported , the University earlier this year revised its NDAB policies to incorporate new definitions of antisemitic and of anti-Palestinian, -Muslim, and -Arab discrimination and harassment.)

The DCAB, chaired by the Harvard College dean, acts in two distinct ways:

For cases investigated by specialized fact-finders (the Office of Dispute Resolution for Title IX cases, the OCC for NDAB cases, or the University Committee on Rights and Responsibilities for multi-school cases involving the University Statement on Rights and Responsibilities), the DCAB receives reports and determines sanctions.

Separately, the DCAB investigates cases of misconduct in its areas of responsibility and determines sanctions.

The latter responsibility is hardly narrow in scope. According to the report, the DCAB oversees cases involving (among others) underage possession or use of alcohol, illicit drugs, physical violence, hazing, harassment, disorderly conduct, vandalism, lying or incivility to Harvard officers, misuse use of campus resources, theft, weapons cases, ID cases, and, of course, those matters arising from protests.

At a minimum, Blair said, she hopes that the committee’s report will help FAS members face future disciplinary matters—routine or extraordinary—“with our eyes open.” Even in the context of the difficult, divisive, stressful, and emotionally taxing issues of community behavior and discipline that arose last year, she said, “As a community, we can manage [challenges like] that and be proud of how well we managed it. These institutions functioned pretty well,” but can be improved. It is in that spirit that the committee made its recommendations, based on its members’ much-deepened understanding of the disciplinary process and the ways it is administered.

How the Process Works

The DCAB “has limited fact-finding capabilities of its own and is not designed to conduct extensive investigations,” so it relies on other bodies’ reports, a response from the student, and other evidence (written and oral statements, etc.). A DCAB subcommittee considers the case and then makes a referral and recommendation to the whole DCAB. The student is represented throughout by the Resident Dean and may request that a personal adviser (an unrelated University officer) be present. The DCAB as a whole assesses the evidence (including the student’s prior disciplinary record, if any) and determines an appropriate disciplinary response.

During most of the current academic year, the DCAB has had 20 members, according to the report: eight senior College administrators, five Resident Deans, and seven other faculty members (three senior lecturers, four ladder faculty members)—but in past years ladder faculty representation has been scant (none in 2022-2023 or 2023-2024). This would seem to be taking delegation of the faculty’s disciplinary responsibilities to an extreme.

The GSAS Ad Board investigates and sanctions academic integrity and social behavior cases; the GSAS dean is chair, and its 18 other members this academic year include six GSAS senior administrators, the FAS Dean for Student Services, the Registrar, one senior lecturer, and nine ladder faculty members.

The Ad Boards may conclude cases with these outcomes:

• scratch: no finding of responsibility (total exoneration)

• take no action: the facts were not or could not be substantiated

• admonish: a warning that suggests serious consequences if a pattern of misconduct or careless behavior develops—notice that a student is in a state of jeopardy

• probation: a one- or two-term period during which any further violations will result in a requirement to withdraw; the student is not in good standing (but that notice is withdrawn from transcripts after the probation ends)

• requirement to withdraw: generally, separation from Harvard for two terms, and a permanent record to that effect on transcripts

• dismissal or expulsion, subject to enactment by vote of FAS’s Faculty Council; dismissed students may be readmitted in rare circumstances by Faculty Council vote, but expulsion is permanent. Dismissals and expulsions are not appealable.

In reviewing these outcomes, the ad hoc committee questioned whether they are “genuinely educational and restorative in nature, in keeping with the [Boards’] philosophy.” (They also seem unaligned with FAS’s December 2023 debate on restorative justice, such as requiring students found to have violated rules to write an apology to those affected, make restitution for loss or damage, undergo mandatory education, or undertake community service—ironically, discussed midway through an academic year that culminated in traumatic disciplinary issues.)

Students may ask the DCAB or GSAS Ad Board to reconsider a ruling, based on either the availability of material new information or evidence of a procedural error.

GSAS students may appeal a requirement to withdraw for more than one term. Undergraduates may appeal a requirement to withdraw or a probation for more than one term. Appeals must be based on a claim that the Ad Board made a procedural error sufficiently significant to change the outcome of its decision, or that the sanction imposed was inconsistent with usual Ad Board practices and inappropriate for the case. When an appeal is filed, the Ad Board sends the case to the Faculty Council’s Docket Committee; if it rules the appeal appropriate based on the allowable criteria, it proceeds to the Faculty Council, which reviews the matter with the Ad Board and votes whether to ask the Ad Board to revisit its decision.

Recommendations for Reform

The ad hoc committee’s most significant recommendations—deliberately cast at a high level, inviting FAS leaders and the Ad Boards themselves to craft and effect the most pertinent changes—include the following.

• Increase ladder faculty engagement on the DCAB. FAS’s rules emanate from the faculty, which are responsible for disciplinary enforcement, so it stands to reason that tenured and tenure-track faculty ought to be more involved in serving on the College’s principal disciplinary body. The committee suggests forming a pool of candidates who are available and willing to serve three-year stints. Doing so, the committee believes, would properly engage FAS in administering discipline, and build a cohort of faculty members who could educate their peers about the process—ultimately “build[ing] trust and confidence in this body to whom the faculty have delegated the administration of discipline.” That “trust and confidence” have been critically absent at moments of crisis, in 1969 and again last spring—as evident in FAS’s May vote to overturn the disciplinary outcome for the students who participated in the Harvard Yard encampment, forcing the ensuing confrontation with the Corporation.

The committee sees two further gains from this recommendation, if effected:

• creating a pool of faculty members informed about discipline who could serve on DCAB subcommittees needed to hear cases when multiple cases arise at once, as in the protests last April and May; and

• building a cohort of experienced faculty members to hear appeals from disciplinary cases, when necessary, under the new appeals process being recommended (see below).

Given current ladder faculty representation on the GSAS Ad Board, the committee saw no need to recommend any changes there.

• Institute a new appeals mechanism. Appeals of Ad Board decisions are now directed to the Docket Committee, and from there, to the Faculty Council. But as the ad hoc committee observes, “members of the Docket Committee and of Faculty Council who currently hear appeals typically have no prior experience of the procedures of the DCAB”—a significant impediment to their work when they are called upon. Instead, the committee calls upon the FAS dean to form an appeals committee—a small group of ladder faculty who have prior experience on the College or GSAS Ad Board, who would be better equipped to decide on appeals when presented. (Alternatively, such a committee could hear the preliminary presentation, as the Docket Committee does now, and then refer it to the Faculty Council to determine whether to direct an Ad Board to reconsider its decision.)

A related recommendation is to limit appeals to cases where the sanction imposed is the requirement to withdraw. If adopted, this change would mean that undergraduates would not be permitted to appeal in cases where the sanction is more than one term on probation. (As noted, GSAS students may not appeal such sanctions.) As a result, appeals would focus on the most serious cases; students could still file requests for reconsideration with the Ad Boards in instances where they are to be placed on probation.

• Other recommendations. The committee recommends that DCAB subcommittees determine whether a rule violation has occurred, through referral from other fact-finding bodies or their own investigations, but not recommend the resulting sanction. (Sanctions are decided upon by the entire DCAB in any event.)

It also recommends that the DCAB and GSAS Ad Board report to the Faculty Council at the end of each semester, briefly summarizing the highlights of their work during the preceding term or academic year. This could at least minimally increase faculty awareness of discipline, desired changes in procedures, and so on, should the Council bring the matter to FAS for discussion.

The committee recommends training for Ad Board members and faculty members who serve on appeals committees. It further recommends that the College and GSAS “develop ways to further educate the FAS community about the work of the Ad Boards.” It recommends no changes in the definition of whether students are in “good standing,” but does recommend developing ways to find out from students subject to FAS discipline what their experience was.

As noted, such changes could be effected, for the most part, through modifications of the language in the Ad Boards’ detailed procedures.

In her letter to Blair, Dean Hoekstra began the process of implementing the recommendations. She specifically endorsed two measures: “to increase ladder faculty involvement in the College’s Administrative Board,” following the “successful model” of the GSAS Ad Board; and “to create an appeals committee comprising faculty members with experience” serving on an Ad Board. She cited the committee’s reasoning that an expanded cohort of faculty informed about the disciplinary processes would in turn educate their FAS peers and “build trust and confidence” in the Ad Boards. Finally, she will “charge the Administrative Boards to review annually their practices, guidelines, and activities”—with the first such review this summer.

Assessment

The ad hoc committee has a reformist mission, in the context of obvious strains in FAS’s disciplinary processes, at a time of extreme community and external interest in the results of those processes. Its recommendations, if adopted, would clearly make FAS members more responsible for owning, and implementing, their rules and norms, and enforcement of same.

In two respects, the committee’s work reflects the limitations of its charge.

Undergraduate advocates of student participation in the DCAB’s work may be disappointed. But Harvard history may not be on their side. Student participation in discipline following the campus upheavals of 1969 and the few succeeding years gave way to criticism of and disengagement from the process. In light of the past 18 months on campus, where students have been sharply divided from one another, it might be especially difficult to introduce any of them to formal disciplinary roles as Ad Board members. Finally, given the committee’s recommendation to build knowledge of disciplinary processes among FAS faculty members through extended service, a set of rotating student members might have the opposite effect. But FAS and Ad Board leaders will have to weigh these issues further.

The recommendations on how to communicate about the Ad Boards’ role and work are also somewhat limited. OAISC and the GSAS Ad Board post broad statistical summaries of their cases each year. Cases are reported within categories covering academic procedure, social behavior, alcohol, drugs, and sexual matters. That satisfies state reporting requirements and complies with federal regulations governing the privacy of student records enacted in 1974—but result in reports that are otherwise unenlightening. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, when there were many disciplinary cases of an extremely serious nature, and before the 1974 regulations, disciplinary reports carefully explained the nature of offenses, ameliorating or aggravating circumstances, and the rationale for the associated sanctions: highly useful, educational material for community members. No such reporting exists now, and the committee did not address whether any such communication is or ought to be possible. In the absence of such materials, no one outside can determine exactly what the bounds of behavior are, nor whether disciplinary measures are applied consistently across Harvard’s schools. (After the 2024 encampment, there were reports that graduate and professional school students were, at most, given probations; it cannot be determined exactly whether that is so, and if so, whether the violations differed from those committed by undergraduates who were more severely sanctioned, or disciplinary bodies ruled differently, or the involved students had differing prior disciplinary records.)

That said, the committee’s report, and its recommendation for regular reviews of discipline in the future, are both an important encouragement for continual self-improvement under FAS members’ scrutiny, and a reminder that FAS members must engage in disciplinary work themselves. That would be consistent with the nature of discipline within an academic community, which is ultimately intended to be restorative and educational. The most important takeaway might be in a concluding reflection, in which committee members underscored the challenges of striking the right balance, but striving to do so by focusing on individual community members’ behavior relative to FAS and University rules and norms, the better to foster the necessary conditions for effective academic discourse:

Reading an [account of 1972 disciplinary proceedings] is a sobering reminder that in a context of significant and politicized disagreements on our campus, it will be difficult for any committee to reach decisions in politicized cases that will prove broadly convincing. The review committee feels strongly that the DCAB and…GSAS Ad Board should continue to adjudicate instances of misconduct that may arise in a broad range of contexts while honoring the University’s commitment to free speech. Specifically, disciplinary procedures should focus on individual behaviors without assessing their motivations or the content of accompanying speech.