One fall day in 1967, Neil L. Rudenstine, Ph.D. ’64, a “recently minted assistant professor,” found himself walking by Mallinckrodt Hall, where a crowd of students had blocked the entry to impede the work of a Dow Chemical Company recruiter, on campus to interview job applicants. “I had never before seen a university disruption,” he writes, and was not much up to snuff on the emerging antiwar movement. But recognizing some of his graduate literature students among the protestors—and sensing a threat to the institution’s “fundamental values”—he stayed to debate with them. They ultimately disbanded, but foreshadowed many more, and far more disruptive, protests to come. Rudenstine, recognized for his role in that nonconfrontational outcome, began his own progress toward a life in administration (as dean of students and later provost at Princeton, his alma mater, and ultimately Harvard’s president from 1991 to 2001): a career that overlapped a tide of rising campus disruptions from those turbulent decades—beginning with Vietnam and extending through black and gay rights and representation, apartheid, and climate change—to the present confrontations over terrorism and war in the Middle East.

Among many other virtues, his new memoir, Our Contentious Universities: A Personal History, is a sensible, calming account of the nature and implications of unruliness within the academy—its title a pitch-perfect example of Rudenstine’s careful diction, and very much of a piece with his worldview and character.

It is no surprise that he mounts a vigorous, ringing reaffirmation of liberal arts, and of the humanities within the liberal arts. Perhaps more of a revelation, to those who don’t know Rudenstine’s academic leadership experiences well, is his perspective on the wider society and culture and their effects on universities. Also his institutionalism: on the differences, say, between a Princeton and a much larger university like Harvard.

More broadly, he is astute in explaining why universities, places for ideas in contention, have become more contentious in the context of changes in society, and the parallel changes in the institutions themselves over time—their vastly expanded scope and scale, creating an increasingly complex and impersonal ethos—and the resulting challenges to leading such communities and sustaining their culture as places of learning.

Two excerpts follow. The first, on the living-wage sit-in at the end of Rudenstine’s presidency, has valuable things to say about the nature of the Harvard community and the new era of protest that has been vastly magnified during the past couple of years (and about a modulated, academic way of responding to such demonstrations). The second presents broader reflections on what the evolution of higher education from liberal arts toward something much more instrumentalist has meant for universities and those they serve: what has been gained, and what lost—but perhaps not, one may hope, irretrievably. —The Editors

A New Age of Protests

In my eighth year as president—in 1999—a new issue (and what I began to believe was a new age) began to emerge among a number of students: the concept of a “living wage.” It was an issue that had already been raised and addressed…by several institutions. Moreover, in the Cambridge area, at least three townships had accepted the idea, and it seemed to many people that Harvard should adopt such a policy for its nonacademic workers.

Part of the reason for the Harvard dispute arose from the fact that some of the less well-endowed professional schools had recently decided to “outsource” their janitorial services to private companies that could do the job less expensively….This helped to relieve the considerable budget pressures of some of the smaller underfunded schools. These actions (plus the fact that a committed group of students believed that Harvard paid many of its workers too little) led to a steady, growing, and more outspoken campaign on the living-wage issue.

When I was asked my views, I said that the university should be seriously concerned about its pay scales, making certain that they were fair, but that I was not in favor of the concept of a “living wage” because it was…really impossible to define. In fact, the few local communities that had already endorsed the concept had arrived at completely different conclusions about the actual pay level that constituted such a wage. Some were noticeably lower (or higher) than others. That seemed completely irrational to me. If the issue were a minimum wage, that was eminently discussable, and if we were paying too little, we could find a way to raise the pay scale.

May 25, 2000, upon announcing his planned retirement as Harvard’s president | Photograph by Jon Chase/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

My response was—I thought—a reasonable one, but it did not have any effect on those who were now publicly and more intensively committed to having Harvard adopt the new policy. Moreover, they demanded that the lowest-paid workers at Harvard should receive at least $10 per hour (which was a much more significant figure in the 1990s…). Most of our schools or units could well afford this (and paid it), but a few might face deficits if the new level went into immediate effect. Nevertheless, it was a reasonable—and definable—goal that we could at least address.

The response of most of the university was revealing. I received hardly any letters or messages from faculty on the issue, although a large number of them later signed a full-page advertisement in the student newspaper, advocating adoption of the proposed new policy. Meanwhile, the main organized union on campus let it be quietly known to us that it would not support a student-led campaign: It had its own distinct agenda and concerns….I continued to feel confident, however, especially because so many Harvard workers were unionized, and we continued to have very good relations with the union leadership. Indeed, a survey of Harvard workers also revealed that more than 90 percent of them were already paid $10 or more per hour.

Then, in the very last months of my final year as president, a group of students, led by Progressive Labor (and SDS) members, became more strident. One day they suddenly took advantage of our building’s open-door policy and entered en masse, taking over the ground-floor offices, setting up a “command-post,” and essentially filling most of Massachusetts Hall.

I was taken totally off guard, and told our staff that we should continue with our work as much as possible. The students, however, were a different breed than I had known from my days at Princeton: This was mainly an angry and bold group and they paid…absolutely no attention to the plight of the Mass Hall secretaries, treating them rudely and impatiently. The irony of how they acted in the presence of “real” workers was not lost on us, and my assistant—Beverly Sullivan—quickly made her way through all our offices, warning the students to change their behavior. This actually had an effect, but did nothing else to alter the basic situation.

Meanwhile, in part of the Yard (in front of our building), many students had begun to set up small tents, creating a kind of camp in support of their fellows inside. This complicated the entire situation, and the two groups communicated regularly by two-way radio. Food was brought to the protestors through our downstairs windows—something that we decided to allow.

The entire action was far more organized, determined, and impervious than anything I had ever before encountered. I immediately convened all my senior staff, including the head of security. What were our alternatives?

I began with two main points: We would not accept the idea of a “living wage,” and we would not call the police to break up the sit-in. The last thing I wanted was to emulate Grayson Kirk of Columbia [1968] or Nate Pusey of Harvard [1969] by having police batter students and throw the entire institution into turmoil…. That left us with two main options: Wait for the students to exit (because we were approaching the end of term, with exams and then graduation); or ask the courts to intervene, ordering the students to evacuate the building or be held in contempt.

We did not come to a conclusion in our first session, but meanwhile the entire situation began to take on even greater proportions. The national leaders of two major unions flew to the university; the elected Cambridge City Council walked through Harvard Yard in a show of support for the students; and Senator Ted Kennedy made a statement, urging the students to continue, stating that Harvard should immediately adopt a living-wage policy.

So the university had suddenly become a national target…: If Harvard changed course, that could help enormously to legitimize the living-wage policy, and other places would be pressed to follow suit. Our options…were suddenly much more complicated, with national union leaders and Ted Kennedy in the battle.

I met with the labor leaders in a long, tense session. They were in one sense respectful, but there was no way that we could possibly agree. By this time, a few days had already passed. My senior staff and I had essentially reached the conclusion that we should wait until the sit-in eventually dissolved. Given the media interest, the national attention to the situation, the national union leaders, and the tent camp on the lawn, I was reluctant to bring in the courts, because there would almost certainly be riot police in attendance—with very unpredictable consequences. If even a few tent-camp students tried to interfere with the court officials or the police, the results could be disastrous. Meanwhile, some alumni and other hardliners were calling for police action and wondered why I did not forcefully move ahead.

It turned out that the wait was very long, and stretched beyond one week into a second, and then beyond. Tempers flared on all sides, and several of us moved to offices outside the building to get our work done. The students showed no sign of being worried about their academic obligations, and I began to seriously doubt myself—wondering whether I had made a major mistake in not going to the courts. The tent camp outside grew larger and I made certain that our security guards would not attempt to physically remove or interfere with anyone who was there.… [W]hat had begun as a local sit-in was now a major public event.

I decided not to change course, even though it was obvious that the students were far more committed and forceful than I had initially imagined. There was not much time before the end of term, however, and in spite of everyone’s growing frustration, it still seemed right to carry on as planned. I remembered that President Ed Levi of the University of Chicago had once waited out a 16-day sit-in, and that gave me a modicum of comfort!

At that point, I was surprised to receive a phone call from Larry Summers, who had recently been elected to succeed me as president. Larry suggested that we should announce the creation of a faculty-led committee to study the entire living-wage issue over the course of the summer….This would provide a legitimate process to help resolve the issue, and I immediately agreed with him. The students would be given a form of victory, while I felt confident that a thorough examination of the issue would not lead—given the unpredictability of defining a “living wage”—to such a major shift in university policy. Outsourcing was a somewhat different issue, and could be dealt with on its own terms. But the living-wage matter…could now be addressed squarely in an orderly, probing way. Meanwhile, a superb committee was established, with University Professor Sid Verba, Tim Scanlon (from the philosophy department), Larry Katz from economics, and other equally thoughtful and exceptional people.

Once the announcement of the planned committee was made public, the students felt victorious, leaving Massachusetts Hall to the cheers of their fellows outside. So my last sit-in ended almost exactly 30 years after my first one. That evening, Angelica [Rudenstine] and I were having a small dinner for some friends at home, and I arrived in good spirits. We had not called the police. We did not agree to the “living-wage” issue. There were no injured students. There would be an excellent committee in place.…The entire experience had in its way been harrowing, but the finale seemed to justify the “harrow,” despite the obvious difficulty of it all. Meanwhile, established disciplinary procedures would move ahead to hear the student cases.

Looking back, I was struck again by the fact that the student protestors had remained steadfastly “detached.” They did not occupy any building related to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences but focused only on the president’s isolated domain. That in itself separated them from any direct relationship with (or influence from) their dean and his staff, quite apart from their teachers. In addition, they were…highly organized, with radio connections not only to other students but also to the media. In other words, they allowed themselves no real human contact that might influence them. No one in Massachusetts Hall, including myself, knew them personally. In all these ways, I felt once again that the scale of Harvard and the idiosyncratic nature of its structure made it difficult to try to build a university community or a unified single institution. If that were true in Cambridge, I thought, what must it be like at larger institutions—or at the “multiversities” described nearly four decades earlier by Clark Kerr [LL.D. ’58; first chancellor of Berkeley and then president of the University of California]?

The sit-in was revealing in another way: It suggested that the future might involve…major societal problems (such as the wages of workers). A new era was awakening, and it was to be a time when various social issues would come into play—and into contention….

Preserving Room for the Liberal Arts

Several large-scale developments in colleges and universities…during the past two to three decades…have made many of our institutions larger and more complex, and often more difficult to run as coherent, unified entities. These institutions are also more controversial [and] more subject to sustained media criticism, as well as to campus protests.…I…concentrate here on a limited number that seem to me to be highly consequential.

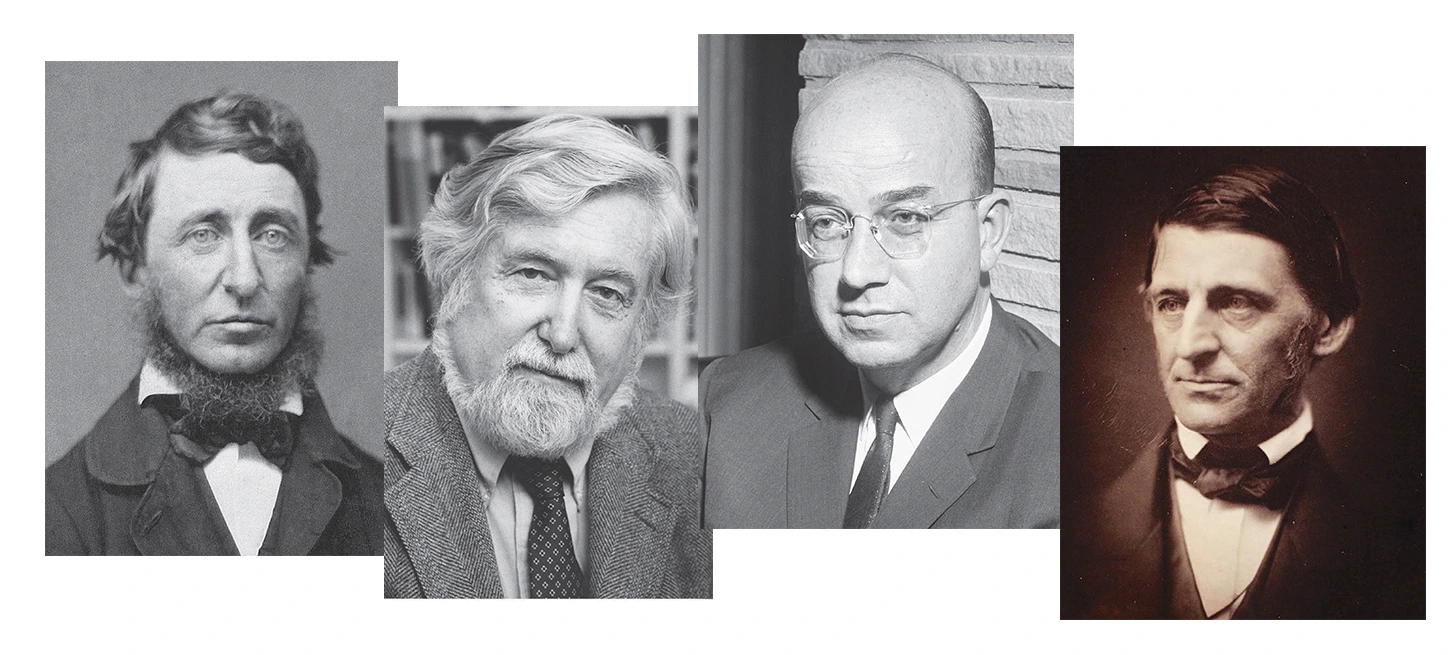

Universities and colleges have several purposes, including promoting the idea that learning has the capacity to enlighten individuals and to free them to live examined and fulfilling lives of thought and action. Henry Thoreau (who deplored his undergraduate years at Harvard) hoped that mankind would aspire to be “Awake”—open to experience and capable of responding to it fully. [Ralph Waldo] Emerson wanted his “American Scholar” to be the embodiment of creative “Man Thinking.” Henry James (who inexplicably attended but then quickly dropped out of Harvard Law School) valued people who were so alert that “nothing would be lost upon them.” These three figures were of course radically different from one another in their personal journeys, talents, preoccupations, and actions. But they shared one significant value: their conviction that the individual…has the capacity to discover significant truths in the face of unfolding experience.

Thoreau sought (in Walden) to track down and corner “nature” in order to discover whether it is at bottom “mean” or not. Emerson’s American Scholar would be courageous and if need be alone, determined to discover truth by following his own perceptions and convictions above and beyond inherited doctrine, religious sectarianism, or established scholarly tradition. And it was James who confessed that he had “wriggled” and “foundered and failed” until he found at last “a general lucid consciousness which I clutched with a sense of its absolute value.” Consciousness could lead to a form of receptiveness and responsiveness in persons “upon whom nothing would be lost” as they encountered reality. So each of the three turned to the individual: to the single being “awake” or “thinking” or “conscious,” committed to discovering truth itself in order to live a life worth living.

Such journeys—such quests for meaning and knowledge that do not necessarily lead to tangible…results useful to society—have always been rare, but they are more so today because of three main pressures. First, we are obviously a much more organized, structured society—with many defined pathways for individuals to follow as they mature. Next…there is a desire on the part of today’s students to pursue professional opportunities, intensifying the phenomenon of careerism among university undergraduates (and their parents). Finally, there has been a steadily growing expectation that our universities will devote themselves more and more to the solution of practical problems useful to society….In short, the modern American university has become more “instrumental”—more pragmatic at all levels—than it was in the decades immediately following World War II….The student or scholar who studies primarily to gain more knowledge about a subject that may seem impractical is rather less in evidence. In retrospect, it seems ironic that the 1950s and early 1960s should have been so persistently criticized for being “silent” and politically quiescent, because that was a moment when the search for knowledge that had meaning—but not necessarily any immediate use—seemed a rewarding and worthwhile pursuit.

In a 1991 talk given by Bernard Bailyn of Harvard’s history department, he wondered what—in the “pragmatic” world that seemed dominant—could be the “value of studying the early Greek epic” or “Byzantine iconography”? Why bother with “the transformation of politics in ancient Rome”?

Bailyn answered his own questions in the following way:

Because these are significant passages in the development of our civilization, because they are achievements of the human mind, because they stretch one’s imagination and intellect, enlarge one’s views of the world, extricate one from parochial environments, and lead one to think about the character and meaning of human experience.

In effect, Bailyn was speaking on behalf of the liberal arts and sciences—especially but not only the humanities—and their decline, and he made the point that those who pursued such subjects now often felt “marginalization and above all ambiguity.” Such subjects in the American university “remain respectable, and they are honored in abstract ways, for their contribution to civilization. But as the calls for action grow louder, these efforts seem increasingly old-fashioned.” Those who call for more university commitment to solving present-day problems often disparage any different conception as being “ivory tower” in nature, but that is a major misinterpretation. The most searching universities have long been committed to studying the “liberal” arts and sciences for reasons that Bailyn described—sometimes to solve pressing problems, but often to enlarge and help sharpen the mind in pursuit of many different forms of knowledge.

Bailyn’s analysis seems a reasonable summary of the situation today….Indeed, as the world continues to be turbulent…beyond any immediate remedy, as the environment becomes swiftly more endangered, as technology becomes more pervasive and our politics more adversarial and importunate, the future of humane “liberal” learning seems clearly to be far less bright, and the need for practical “instrumental” solutions more urgent. It is difficult to imagine many leading figures in our present society echoing words that might resemble those spoken more than a century ago (in 1902) by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in a speech when he was dedicating the new law school building at Northwestern University. In response to hypothetical questions about the purpose of the building, Holmes acknowledged that students might come in the hope of ultimately having a successful business career (or even a career in law!), but he insisted that the building…had much more to offer. It offered the chance to think philosophically about all of one’s studies, in a way that enabled one to consider problems and issues far more deeply and imaginatively than would otherwise be the case. A university, Holmes said, is “open to all idealizing tendencies” and is “above other institutions the conservator of vestal fire.” It inspires some students not simply to study their “subjects,” but also to advance their understanding of life—even to paint works of art or to write poetry. In these and other ways, “those who come to the university want to press philosophy to the uttermost edge of the articulate, and to try forever after some spiritual ray outside the spectrum that will bring a message to them from behind phenomena. They love the gallant adventure which yields no visible return. I think it the glory of that university which I know best, that under whatsoever reserves of manner they may hide it, its graduates have the romantic passion in their hearts.”

Perhaps no one was more insistent and even vehement than Robert Hutchins—president of the University of Chicago—in continuing to defend (during the 1930s and 1940s) the liberal arts, and his chosen foe was the “vocational-informational philosophy of education that is coming to prevail” as a result of the apparent advances in Italy (and Germany) where efficiency and “useful” science had apparently created modern “successful” nations with tangible, pragmatic results:

The trains, we are told, ran on time. The beggars had disappeared. There was less crime than there is in the United States. Italy had gained power and prestige....[But] the Italian state is not a state at all. It is an organization of force....It denies the proper end of the person.

As an antidote, Hutchins proposed “the communication of our intellectual tradition and training in the intellectual disciplines”:

This means understanding the great thinkers of the past and present. It means a grasp of the disciplines of grammar, rhetoric, logic, and mathematics; reading, writing, and figuring.

Hutchins was both extraordinary and fiercely headstrong—one of the (young) “giants” whose ultimate legacy was certainly ambiguous. Nevertheless, he had a conception of the liberal arts that was emphatically rational, ordered, and disciplined (rather different from Holmes’s more romantic notion). It eventually expressed itself in Chicago’s general education program and was also—in a somewhat different form—a view that prevailed when I was an undergraduate at Princeton. I and most of my colleagues tended to study quite broadly across the liberal arts and sciences, relatively free from the pressure of preparing for a career. We were in no sense superior to today’s students—indeed, I think that the best of today’s students are more intellectually capable, more sophisticated, and more aware of political and international affairs than most of us were. And it is impossible to criticize current undergraduates for being the product of family, social, economic, and other circumstances that bear on them to be “professional” or career-minded at a much younger age than we were. But the fact remains that we live in a new reality, and it affects not simply undergraduate majors but also the nature of research, professional education, problem-solving, and the very disposition of the university itself.

Some research, for example, can and should be directed toward the solution of identifiable practical problems (such as the cure of diseases, or the effort to improve certain technological processes, or the remedy of particular social ills); but it can and should also be aimed at the understanding of far more basic problems that are important but have no immediate uses. And here the change has clearly been in the former direction—toward “instrumentalism.”…Basic research now represents only about one-sixth of the nation’s spending on research and development (R&D). Indeed, two-thirds of all federal spending is on the “development” of products.

This diminishment of basic research in many sciences has been “invisibly” expensive to the nation because many of the most crucial discoveries—with the most consequential implications—have historically resulted from basic research that had no useful end immediately in sight. The discovery of the structure of DNA by Crick and Watson is one such example. They knew that the discovery would be enormously significant and would lead to a myriad of applications, but they did not undertake the effort to solve a specific practical application—all that came soon enough.…

Ideally, the university should be constituted in a way that enables it to engage with the practical problems and challenges of the present while it also avails itself of, and makes vitally available to its students, the apparently “useless” knowledge and insights of the past and present. The university must in this sense be multifaceted.…[T]he best institutions attempt to remain so. But much of what has happened in recent decades—whether in terms of new courses, new programs and departments, and even new professional schools—has been motivated by the effort to find solutions to immediate problems. In this sense, many universities are simply less concerned with truth—in all its different manifestations—than in some earlier eras.

Nor does this movement show any signs of reverting to a time when higher education maintained a reasonable distance from the world of current affairs, just as it simultaneously engaged—in other respects—with the pragmatic world of “action.” Indeed, nearly 60 years ago, Clark Kerr observed that “knowledge is now central to society. It is wanted, even demanded, by more people and more institutions than ever before. The university as producer, wholesaler, and retailer of knowledge cannot escape service.” This was uttered partly as something admirable, and partly as a lament. Of course, Kerr’s university was publicly funded, so its service function was in certain respects intrinsic to it, but even Kerr was concerned about “slavishly” fulfilling so many tasks. Private institutions…clearly have had a somewhat different—and broader—mission which, for many reasons, has simply been attenuated.…

In his book Troubled Times for American Higher Education: The 1990s and Beyond, Clark Kerr quoted John Gardner discussing other changes in higher education:

The historical trends have been toward larger scale organizations—and this puts more emphasis on “leadership teams”; toward fractionalization of constituencies.

Meanwhile, other offices—vice-presidents, directors, provosts, and vice-provosts—have grown in number and authority. Kerr singled out the provostship for special comment:

within the administration, the role of provost has grown greatly in importance—presidents were once their own provosts. The creation of the provostship (or academic vice-presidency) and the rise of provosts or the new persons of power on campus is one of the least recognized but most significant changes of all. Presidents seldom teach anymore…and administrative staffs have grown much faster than academic, often twice or three times as fast.

Not all institutions have by any means followed a similar pattern—and provosts have proved to be a blessing!—but the overriding tendency has been in the direction that Bailyn, Kerr, Gardner, and others have charted, beginning 30 or 40 years ago and then accelerating after the turn of the century. I was provost at Princeton from 1977–88, and introduced the provost’s office at Harvard in the early 1990s. My only defense is that there was only one vice-provost throughout my Princeton and Harvard years.…

[O]ther important changes have also had an impact on the functioning of many private colleges and universities….[T]heir slow but steady increases in size (often as a result of fund-raising campaigns) have led to the creation of more quasi-independent programs, institutes, centers, professional schools, and other units. The addition of more discrete parts…means less institutional unity and coherence, and more institutional dispersion. Individual units tend to operate as relatively autonomous units on their own, cultivating their own donors and “friends groups,” while determining their own strategic directions. This can lead to exciting results and substantial successes—but also to unexpected waywardness and unmonitored or unchecked excesses of various kinds.…

…[A]t the graduate-student level, the situation has become dire. Even much-reduced numbers of enrolled students have proven to be too many for the extremely small number of jobs available—especially but not only in the humanities.

We have…noted that “tenure-track” and tenured positions have steadily declined in colleges and universities, whereas part-time “adjunct” faculty positions have greatly increased in number: They now represent about half of all academic posts. The academic profession has simply become a less and less desirable (or feasible) career since the boom days from the late 1940s to about 1970. And adjunct faculty are now beginning to unionize at many institutions.

When Clifford Geertz [Ph.D. ’56, in anthropology, LL.D. ’74, ultimately professor at the Institute for Advanced Study] delivered his Haskins Lecture [sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies] in 1999, for instance, he described his own experience studying the liberal arts at Antioch College in the 1950s (my own era at Princeton). He wrote:

I simply took just about every course that in any way looked as if it might interest me, come in handy, or do my character some good, which is the definition, I suppose—certainly it was Antioch’s—of a liberal education.…The result of all this searching, sampling, and staying loose…was that, when I came to graduate, I had no more sense of what I might do to get on in the world than I had when I had entered.

What one was supposed to obtain there, and what I certainly did obtain, was a feeling for what Gerard Manley Hopkins called “all things counter, original, spare, strange”….One might be lost or helpless, or racked with ontological anxiety, but one could try, at least, not to be obtuse.

Geertz became…an academic and—rather later, in the 1990s—he found himself wondering whether his own undergraduate experience, and his own kind of academic career, was feasible any longer. He noted that there was “a fair amount of malaise about, a sense that things are tight and growing tighter”—that it was no longer “wise just now to take unnecessary chances, strike new directions, or offend the powers”:

The question is: Is such a life and such a career [as mine] available now? In the Age of Adjuncts? When graduate students refer to themselves as “the preunemployed”? Has the bubble burst? The wave run out?…

[Until] a few years ago, I used blithely, and perhaps a bit fatuously, to tell students and younger colleagues who asked how to get ahead in our odd occupation that they should stay loose, take risks, resist the cleared path, avoid careerism, go their own way, and that if they did so, if they kept at it and remained alert, optimistic, and loyal to the truth, my experience was that they could get away with murder, could do as they wish, have a valuable life, and nonetheless prosper. I don’t do that anymore.