Donald Trump’s name was never spoken during Tuesday morning’s Phi Beta Kappa Literary Exercises, but you could still hear it loud and clear. It was perhaps loudest during a standing ovation for President Alan M. Garber. At the top of his oration, Rakesh Khurana, the Danoff dean of Harvard College, turned to Garber, who was seated silently on stage—a part of the ceremony but not one of the speakers. “I couldn’t be prouder,” Khurana said, “to stand here today with President Garber, who has modeled what it means to stand for principle over expedience in the face of these threats. His steady leadership has reminded us that the legitimacy of our institutions depends not just on what we know, but how we act and commit to veritas.” The audience clapped, then cheered, then rose to its feet—and kept applauding until Garber, looking abashed, stood up and waved everyone back into their seats.

But Trump, and the onslaught his administration has launched against Harvard—which continued Tuesday with a new declaration that the government would cancel $100 million in federal contracts with the University—remained the subtext of the entire event. It was there in the opening invocation of Matthew Potts, the Pusey minister in the Memorial Church, who quoted Ralph Waldo Emerson’s call in 1837—standing before another Phi Beta Kappa (PBK) audience—for bravery in academia: “He said, in dangerous times, the true scholar does not turn away from vexed questions or contentious politics,” Potts recited. And it seemed to be there, too, in the anthem sung by members of the University Choir and the Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum. The song was a Langston Hughes poem, “To You,” set to music: “Outside our world of here and now, / Our problem world.” The melody was full of blue notes.

Trump was there in PBK Alpha Iota chapter president Karen Thornber’s references to the attacks on Harvard and higher education, and to the backlash and division that “sometimes seem insurmountable.” One of the day’s three teaching prizes was awarded to political scientist Steven Levitsky, coauthor of How Democracies Die (2018) and a leading scholar of democratic backsliding and authoritarianism. Levitsky is a professor of government and the Rockefeller professor of Latin American studies. And before handing him the award, PBK chapter treasurer Logan McCarty read from one of the student nominations, which recalled a class in which, “showing pictures of South Korean protests over the recent declaration of martial law, [Levitsky] nearly shouted, ‘That's how you defend democracy!’”

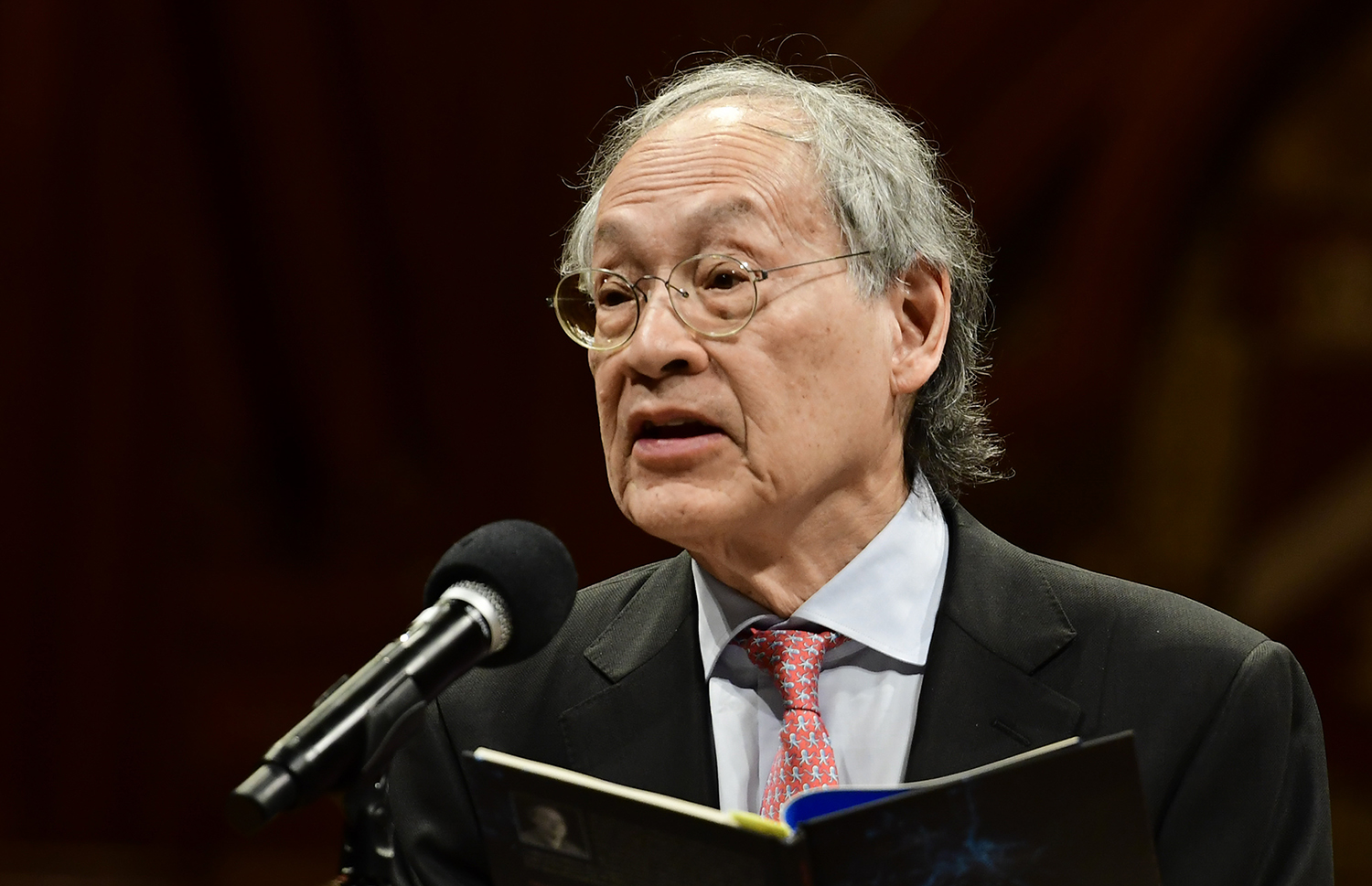

The ceremony’s two main speakers are both children of immigrants. Poet Arthur Sze was born in New York City after his parents arrived from China. He is a professor emeritus at the Institute of American Indian Arts, a public tribal land grant college in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and he won a National Book Award for Sight Lines (2019) and was named a Pulitzer finalist for Compass Rose (2014). His poems, Thornber said in her introduction, “gather and connect the fragments of the world….It’s a way of seeing and a way of being at a time when our world feels increasingly fragmented.”

The other speaker was Khurana, who was born in India and moved to the United States with his parents as a child. He recalled how, in his immigrant home, “Education was sacred…. Universities were a symbol of possibility, of knowledge, of belonging in a world that might otherwise only see the color of our skin. They urged us to excel in school, not out of vanity, to make ourselves legible to a society that might otherwise overlook us.”

But he also reflected at length not only on how Harvard finds itself under threat from the Trump administration but also on the deeper question of higher education’s “legitimacy crisis” and the real problems that give rise to it. “As we stand up for our principles, we also need to stop and take stock of what we owe to society,” Khurana said. In recent decades, he noted, higher education has become more stratified and inaccessible, more expensive, more focused on prestige than on the public good.

“The university’s mission needs to be understood not only as intellectual, or producing research—it is moral,” he said, reiterating a long-held conviction. “This is why criticisms of higher education carry such force. When we’re critiqued, we are not accused merely of inefficiency; we’re accused of hypocrisy. And when we are praised, it’s not just for producing graduates, but for embodying ideas.”

Those hypocrisies matter, he added: “Even when we teach the values of fairness and inclusion, universities like Harvard are also deeply entangled in systems of distinction.” He praised the work of the College’s Intellectual Vitality initiative, which tries to foster genuine, if difficult, conversations on campus among people who disagree, sometimes deeply. But he pushed the graduates in front of him to do more, not to “move fast and break things”—a motto originally coined by Mark Zuckerberg ’06—but “to move thoughtfully and repair what is broken.”

“We live in a time when confidence often substitutes for understanding, when conviction is mistaken for credibility, and when complexity is flattened by outrage,” Khurana said. “But truth, veritas—real, tested, enduring truth—emerges slowly, and must be uncovered, and recovered. It demands humility, evidence, skepticism, and the willingness to revise one’s view in the face of erudition and better arguments.”

That sentiment seemed to recall the closing lines of a poem that Sze had read a few moments earlier, titled “Anvil”:

when in our bodies we sway and flood,

when you bloody your hands,

when the mind like this Earth is struck and tilts its axis,

when, under summer stars, you have built a cabin in the wilderness,

when you gaze at Aldebaran and sense a first frost on the grass,

when in our bodies we ride the waves of our Earth,

here is the anvil on which to hammer your days—