On Saturdays, the Science Center comes alive with nearly 150 excited kids playing with LEGO bricks, setting up dominoes, and laying out tape on the floor. They’re participating in math enrichment—on the weekend, no less—but it’s neither rote memorization nor intense competition.

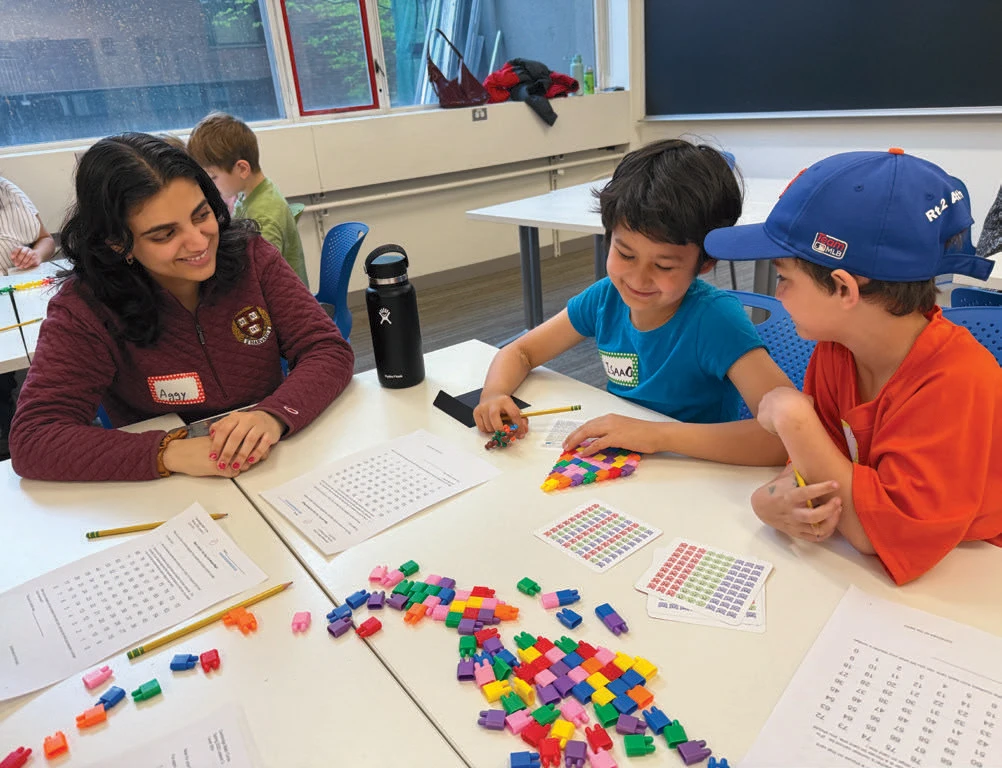

Instead, it’s an activity called Math Circle. The younger kids, from first to third grade, might be using toys to explore basic spatial imagination, or tape to make a sorting network. The older students, from fourth to eighth grade, might be placing dominoes to learn about the Fibonacci sequence or listening to a mini lecture from a member of the Harvard math faculty.

The program, offered by the nonprofit Cambridge Math Circle (CMC), pulls many of its teachers from among Harvard professors, alumni, and students—all drawn to a math education that, they say, is deep and joyous in equal measure.

The concept of extracurricular math circles originated in the Soviet Union and Bulgaria more than a century ago. Mathematicians might come to school and teach advanced math concepts, or groups might convene to discuss applications or deeper research questions. Mira Bernstein, Ph.D. ’99, a graduate of the Harvard math department, and Nataliya Yufa, who co-founded CMC in 2018, agreed that this type of creative math pedagogy needed better representation in American schools.

“The more I learned about it, the more I saw that math education was particularly regimented for schools with many low-income children,” says Yufa, who holds degrees in math, physics, and math education. She participated in a math circle as a youngster in Ukraine and later ran a math circle in Texas. “We realized that we needed to create a brand-new kind of program, a different kind of math circle, which would be welcoming to every student.”

Yufa spoke to parents she knew from the Cambridge school district, including Harvard faculty and alumni. Jacob Barandes, Ph.D. ’11, a senior preceptor in physics, says he quickly grew excited about how the program used “lots of puzzles, lots of riddles, lots of discussion, lots of building.”

“Mathematics is more creative than most things that people do. It’s as creative as the best art or music.”

“I have very strong opinions about the way that we introduce children to mathematics. Generally, my feeling is we do it incredibly badly,” he says, citing Paul Lockhart’s A Mathematician’s Lament, a 2009 book that critiques the state of K-12 math education. “Mathematics is more creative than most things that people do. It’s as creative as the best art or music. And that’s surprising to people. They think mathematics is a set of procedures and rules to be memorized and practiced.”

Barandes, who serves on CMC’s advisory board, is one of several members of the Harvard math department who have taught in the program and enrolled their own children. Professor of mathematics Laura DeMarco, another advisory board member, helped Yufa reserve classroom space in the Science Center. DeMarco has also taught CMC students about her work in fractals and encourages Harvard math students—particularly undergraduates—to become teaching assistants.

“Students are being exposed to things that we consider so important. It’s mathematics,” she says, “but it’s also the joy of mathematics. This is what I live for.”

The program also gives faculty who work in the theoretical realm a chance to talk about math in more concrete terms. Robinson professor of mathematics Lauren Williams, another advisory board member who was awarded a MacArthur “genius grant” in 2025 for her work in algebraic combinatorics, says she spoke to curious children earlier this year about triangulations of polygons and how they applied to shallow water waves.

“Pure math research often doesn’t have any immediate or obvious practical applications,” Williams says, “so supporting the education of young children—where I can see the impact and excitement on their faces right away—is a nice counterpart to that.”

Amrita Ahuja, Ph.D. ’09, whose two children participate in CMC, says the program serves students who might not be interested in competitions or more traditional math extracurriculars.

“The kids are taking the approach of a researcher in math, or an explorer in math, rather than of a student who’s coming to learn specific curricular skills,” she notes. “It’s really creative exploration in the way that research can be: driven by love of subject and interest in the material.”

The CMC curriculum includes machine learning, combinatorics, graph theory, probability theory, number theory, set theory, infinity, and basic calculus. Students who already excel in math get value from CMC, instructors say, but so do students who don’t love traditional math curricula.

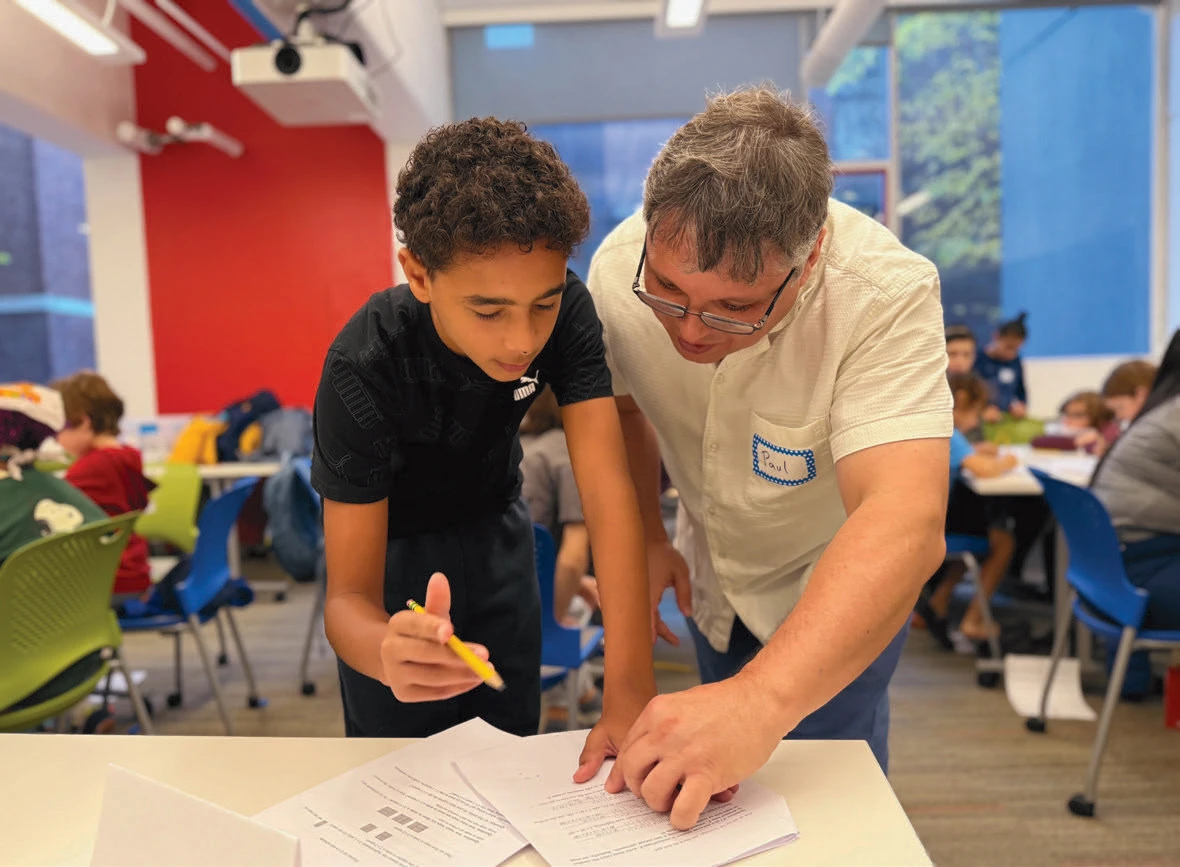

“Everybody’s going to use a little bit of math later in life,” says MIT mathematics professor Paul Seidel, R.D.I. ’15, who brought LEGO sets and dominoes to the Science Center as a guest lecturer one recent fall morning. “It’s not going to be extremely complicated math, but it would really help you if you had an attitude of, ‘Yeah, this can actually be okay. I can do this.’”

CMC also offers Zoom classes, a summer camp program, and math circles at local schools. Overall, the program serves more than 1,000 students per year; half of them receive financial aid. Due to the program’s growth, Yufa says, she’s in the early stages of fundraising so she can continue offering aid.

Amazir B., a seventh-grader, has been attending CMC since he was in third grade. He’s always seen himself as a “math person,” but says the program has helped him grow.

“At school, it’s more structured—they give you a specific way to do a problem. Here, they explain to you the problem so you can fully understand how it works,” he says. “It shows me the beauty and the fun in math: you’re working very hard to understand something, and then it’s that joy when you find the answer.”