The prototype of the silver-spoon baby, Paul Joseph Sachs was born in November 1878 in New York City, the eldest son of Samuel Sachs (a partner in the international banking firm of Goldman, Sachs & Company) and Louisa Goldman Sachs (the daughter of partner Marcus Goldman). His happy childhood included trips to Europe with his father that featured frequent visits to the great art museums. He attended his Uncle Julius Sachs's School for Boys and Collegiate Institution, whose graduates included the scions of New York's most prominent Jewish families.

|

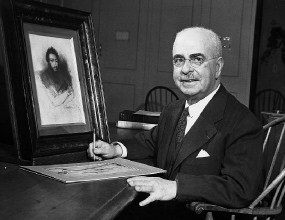

| Collector, connoisseur, hands-on teacher, Paul J. Sachs blended appreciation for art objects with the practicalities of museumship. |

| Photograph courtesy of the Harvard University Archives |

There could be no possible choice of college for him but Harvard. But in 1895, in "a humiliation that rankled him for years" (according to art historian Sally Anne Duncan), he failed his entrance exams, passing German, French, and history, but flunking Latin, Greek, math, and science. After being tutored intensively for a year and studying diligently in front of a poster that read "I must, I will, I can," he was finally accepted. At Harvard, not surprisingly, he focused on French and other modern languages, philosophy, and particularly the fine arts. One of his principal influences was Charles Eliot Norton, whose course, "The History of the Fine Arts as Connected with Literature," was the first of its kind in the United States. (Sachs later purchased Norton's home, Shady Hill, for his own family.)

During the summers, Sachs worked at the family firm. After graduating in 1900, he joined the business, becoming partner a year later. One of his Harvard professors, Charles Herbert Moore, had offered him an assistantship, but it paid only $750, and his father had refused to supplement the salary. "But...," he wrote in his memoirs, "I vowed never to give up the thought of an ultimate professional career in art."

In 1909, Edward Waldo Forbes became director of the Fogg Museum, and in 1911, he asked Sachs to join the Fogg's visiting committee. "This invitation is an opening wedge," Sachs excitedly told his wife. "My foot is in the door." In 1913, he was appointed chairman of the visiting committee, and within a year, Forbes offered him the assistant directorship of the Fogg. Sachs lost no time in accepting, and soon retired from business. "A great many people on 'the Street' thought I was a damn fool and couldn't understand it," he later recalled. One letter, from an English colleague, said, "I always knew you were fond of 'queer things,' but never guessed you would hide away in a musty museum and hobnob with Egyptian mummies."

At first he did not receive a salary, but even so, as Forbes observes in his memoirs, "these days," someone with Sachs's lack of academic credentials "wouldn't have a snowball's chance in hell" of getting such an appointment. As Duncan explains it, "Forbes saw money in Paul Sachs," a link to successful Jewish alumni and art patrons, to the banking community, and not least, to potential contributions from Sachs himself. To Sachs, writes Duncan, the move represented a kind of continuum: he called it "a short leap from the hallowed atmosphere of the banking house to the construction of a correspondingly rarified space in the museum, a space which established a well-ordered universe for the presentation of capital of a different sort...."

During World War I, the five-foot, two-inch Sachs, who was too short for the armed forces, served as an ambulance driver and administrator in Paris for the American Red Cross. When he returned to Harvard, he was appointed assistant professor of fine arts. He moved steadily up the academic ladder, eventually becoming department chairman; in 1932, he was appointed a visiting professor at the Sorbonne and lectured at other leading European universitiesa major coup that introduced the Old World to American achievements in art research and museum management. In 1942 Harvard awarded him an honorary doctorate as a "lover of the fine arts, who deserted a business career to become an accomplished teacher."

As chairman of the committee on personnel of the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas during World War II, Sachs recruited many of his former students to hunt down looted artworks and oversee their return to their owners; more than 15 million items were located. He and Forbes retired from the Fogg in 1944, but Sachs continued to teach the museum course through the 1947-48 academic year as an emeritus professor and honorary curator of drawings. He died peacefully in his library, surrounded by his books, prints, and art, in February 1965.