Abbott Lawrence Lowell, the University’s president from 1909 to 1933, looms large in Harvard history, repeatedly championing academic freedom and helping to create the undergraduate House system. “Less heroic was Lowell’s role in two disputes that became public in 1922,” wrote John Bethell, former editor of Harvard Magazine, in Harvard Observed, his history of the institution during the twentieth century. “One arose from the discovery that black students had been barred from the freshman residence halls. The other stemmed from Lowell’s attempt to impose a quota for Jewish applicants to the College.” Even as the first Jewish Overseer was elected in 1919, and the first Roman Catholic member joined the Corporation in 1920, “That Lowell would countenance exclusionary policies angered many alumni and friends.”

Facing an application for a black student to reside in the freshman facilities, Lowell himself wrote, “In the Freshman Halls, where residence is compulsory, we have felt from the beginning the necessity of not including colored men.” As for Jewish applicants, he wrote in 1922 that “anti-Semitic feeling among students is increasing, and it grows in proportion to the increase in the number of Jews,” so he proposed, “in the interest of the Jews as well as of everyone else,” to reduce Jewish enrollment to 15 percent of the total (down from 20 percent or more)—a measure he subsequently effected. And during 1920, an ad hoc disciplinary tribunal, made up of administrators, expelled eight students and a lecturer for homosexuality.

It is in this context that Goldman professor of economics David I. Laibson and Faculty of Arts and Sciences dean for faculty affairs and planning Nina Zipser, who become faculty deans of the Lowell family’s eponymous House on July 1, recently advised students that when they move into the renovated facility in the fall semester, they will find different art hung in the dining hall: “While maintaining many portraits of eminent Lowells from the old dhall makes sense to us, we plan not to reinstall at least two particular Lowell family members from the old dhall: Anna Parker Lowell (1856-1930) and her spouse,” the president. After noting his educational importance to the University, Laibson and Zipser continue:

[I]n other important ways, he was a person behind his times. As president of Harvard, he was responsible for intensifying racism, anti-Semitism, and homophobia at Harvard. He actively pursued policies that animated and institutionalized these prejudices despite contemporaneous resistance from other members of the Harvard community, including the Board of Overseers.

They do not propose to expunge Lowell’s memory. The House name is not changing (a different circumstance from, say, Yale’s decision to rename its Calhoun College, named in the 1930s for the alumnus who was the foremost Southern champion of slavery; or Princeton’s debate about whether to retain Woodrow Wilson’s name for its public-policy school, despite his deep racism). Indeed, the faculty-deans-to-be continue:

Not returning Abbott Lawrence Lowell to our dhall does not mean that we want to erase him from our history. Such an erasure is not possible and, in our view, is not desirable. We should not ignore or hide our history. We need to keep talking about Abbott Lawrence Lowell with each new cohort of Lowell residents (discussing both the good and the bad that he contributed) whether or not he is hanging over us while we’re eating Cheerios.

We also want to emphasize that there is another portrait of Abbott Lawrence Lowell at Harvard, which is currently hanging in University Hall in the Faculty Room. We will arrange visits to the Faculty Room for Lowell residents (and any other interested members of the Harvard community) to see that portrait and discuss Abbott Lawrence Lowell’s fraught legacy.

Through in-House discussions as well as trips to University Hall (or wherever his portraits are hung or stored in the years ahead), we want to remember and learn from the legacy of Abbott Lawrence Lowell. We will do this without having him join us for all of our meals. We will remember him without eating with him in our home. Lately, we’ve heard that some Lowell students and tutors have independently come to similar conclusions about how we should remember him.

And they plan to begin that conversation, in part, by inviting the community to weigh in on the question of whether the bust of Abbott Lawrence Lowell, on display in a House courtyard before renovation, should be returned to the site:

This is a slightly less imposing and oppressive location than our dhall, but the courtyard location is still in our communal home. For the same reasons we wrote about above—Lowell House is a home and not a museum or an historical archive—we believe that this bust should not be returned to Lowell House. However, we want to hear from you about this.

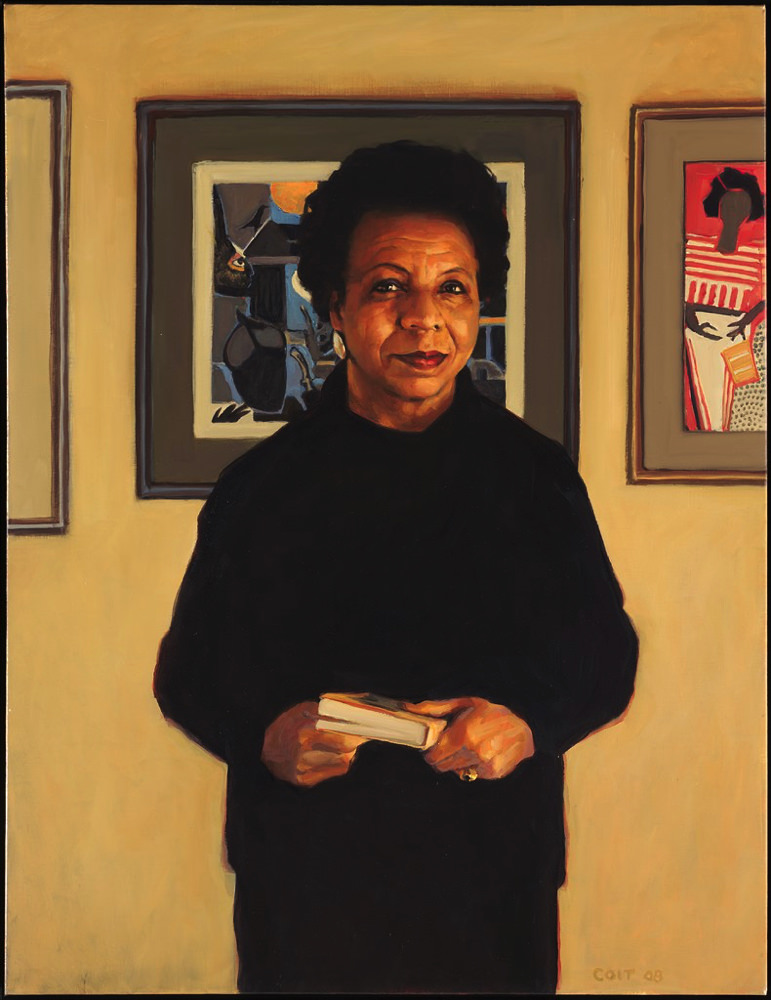

Stephen Coit, Florence Ladd, 2008. Oil on canvas.

Photograph Courtesy Harvard Art Museums Harvard University Portrait Collection, Commissioned by the Harvard Foundation, 2008, H847

In the most important respect, of course, Lowell House has already moved beyond the president’s discriminatory record: the current masters (as they were known when they were appointed 20 years ago), Wertham professor of law and psychiatry in society Diana L. Eck and Dorothy A. Austin (formerly associate minister at Memorial Church), were the first same-sex couple chosen to lead an undergraduate residence.

Continuing their symbolic makeover of Lowell House’s iconography, Laibson and Zipser also announced that the dining hall will feature portraits of Eck and Austin, and of Florence Ladd, director of the Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute at Radcliffe College from 1989 to 1997, a member of the House’s senior common room (and of this magazine’s Board of Incorporators). Both were created by Steve Coit ’71, also a member of the Lowell senior common room.

The changes afoot in Lowell House may be just the first of their kind on campus. In February, as part of plan to implement the recommendations of the University’s task force on inclusion and belonging, the College organized a Working Group on Symbols and Spaces of Engagement at Harvard College. Its charge reads:

To examine how our campus spaces, symbols, and programming advance an inclusive learning environment. The group will deliver a guiding document that explores how Harvard’s history, current spaces, and symbols impact the experiences of our diverse student body; evaluates current programming and training that enable students to engage with difference; and identifies opportunities to create new programs and spaces for programming that promote engagement and dialogue among and across our diverse student body.

Its chair, professor of Indo-Muslim and Islamic religion and cultures Ali Asani, discussed its work in this interview.

Stay tuned for the working group’s findings about the impacts on students of Harvard’s portrait collection and other symbols of its history, and its recommendations for change.