|

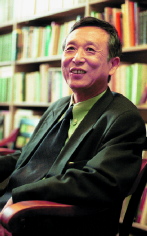

| Nobel laureate Gao Xingjian emphasized the literary qualities of his work, not the political conditions that make him an exile from his native land. |

| Justin Ide/Harvard News Office |

Harvard-Yenching professor of Chinese history and philosophy Tu Weiming, director of the institute, who introduced Gao, noted that he was the first Chinese writer to receive the Nobel Prize--a sure sign that his work has supranational significance, given the absence of Chinese from the Nobel committee. The mosaic of ethnicities in the audience also testified to Gao's worldwide impact and appeal. Soul Mountain is still banned in the People's Republic of China, where Gao's work has not been published since 1986. (He has lived in Paris since 1987.) But it appeared in Taiwan in 1990, in a French translation in 1995, and in English last December, and through its efforts to explore the inner landscape of the soul, Tu said, the novel "developed a new genre."

Lauded for its innovative use of language, Soul Mountain explores a writer's journey through China. The narrative is modeled on Gao's own five-month, 9,000-mile trek through remote areas of Sichuan Province and along the Yangtze River, undertaken in 1983 after learning that he had been incorrectly diagnosed with lung cancer and was also in danger of being jailed. But as the Swedish Academy noted upon awarding Gao the literature prize, Soul Mountain is only part of "an oeuvre of universal validity, bitter insights and linguistic ingenuity, which has opened new paths for the Chinese novel and drama."

In his address, Gao focused on the relationship between freedom and literary creation. All writers face pressures of some type, he argued--censorship in a totalitarian society, market pressures in a capitalist society. Speaking through translator Eileen Chow, assistant professor of Chinese literary and cultural studies, Gao challenged writers to stand up to these pressures. Literature, which holds forth the possibility for creation of a world through one person, independent of outside forces, is the only way to "achieve limitless freedom within oneself," he said. "Therefore, people need literature."

Gao stressed that the way for the writer to achieve this freedom was not to effect social change by attempting to speak for the masses, but to speak for himself. "A writer should not be a judge or a critic," he said. "The writer's task is to observe the world and leave a record."

Gao called on writers to pursue freedom by testing the outer limits of language. "The language we use is one that's been passed down from our predecessors and used many times," he said. "But within its outer limits are limitless possibilities." In his Nobel lecture, Gao called language "the ultimate crystallization of human civilization." Through its use of the pronouns I, you, he, and she in reference to the protagonist, Soul Mountain explores human consciousness and the process by which it crystallizes into language, he told his Harvard listeners.

But what if that process is confusing to the reader? In response to a question, Gao stressed the auditory elements of the text. "When I write," he said, "I must listen to music. My first drafts are most often written by speaking into a tape recorder. In many ways, my writing is much more about its auditory quality than its linguistic."

Yet the text does have a structure. Mabel Lee, who translated Soul Mountain into English and came to Cambridge for Gao's talk, said in a subsequent interview that she found the novel similar to "one big poem, with different rhythms and different beats," which she did her best to preserve. Each chapter within the novel had "an internal spirit, an essential feel that held it together," said Lee, who is honorary associate professor in Chinese studies at the University of Sydney.

The playfulness of Gao's work truly sets him apart, and guarantees that his style will never stagnate, Lee said. "It's got to continue to be fun for him," she added. "There's always another mountain to climb."

~ Elizabeth Gudrais