Ahhng...ahhng...that strange sound somewhere between a ring and a buzzer announces a fire drill at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School. Lines of students slowly pour out onto the grounds of the large, comprehensive high school. It's a warm, sunny October day and students stand in clumps, most of them happy to be outside.

Among the students and teachers, security guards and guidance counselors, assistant principals and school aides, Pedro Antonio Noguera is in his element. A tall, broad-shouldered figure with a warm manner, Noguera chats with a security guard about a student who approached each of them to hit them up for a quarter; engages with the assistant principal about a forum held at Harvard's Graduate School of Education the night before; and talks with another student who has recognized him from a previous visit.

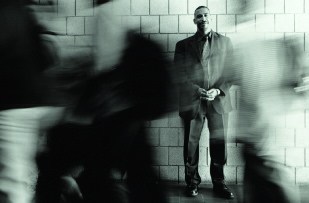

|

| Noguera, at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School, wants to know "where kids get motivation and resilience." |

| Photograph by Flint Born |

None of this is particularly remarkable, except for the fact that Noguera is a researcher, a sociologist who studies urban education. Unlike many social scientists and social-policy experts, who examine an institution as if it were a fruit fly, picking it up with tweezers to put it under the microscope, Noguera walks comfortably through the halls, attuned to the rhythm of the place, talking easily with those he encounters, while absorbing the nuances of the school's culture.

Noguera, who was lured from the University of California-Berkeley last year to become the Dimon professor of communities and schools at the school of education, has been studying urban education for 20 years. But his knowledge is an insider's. He has been a high-school and middle-school teacher (often in the same schools he is studying), and a member and president of the Berkeley school board. He was founder and director of the Diversity Project, a four-year, in-depth study of the achievement gap between white students and students of color at Berkeley High School, which involved parents and teachers in the process and has helped guide change. More than an activist-academic, he is what he calls a "critical supporter" of or a "pragmatic optimist" about urban schools--someone who has great hope for what schools can do, but who can cut through the veils of rationalization and defeat and push participants to reconsider what they are doing.

Urban schools--read schools serving the poor, the working class, immigrants, mainly students of color--need pragmatic optimists now. Although the "crisis" in education was first broadcast 20 years ago, the clarion call has changed to white noise behind the national discourse over education, which in the last election primarily revolved around how many national tests to mandate. There was almost no talk about what to do with those scores, how to remake those schools, how to make them responsive to the students they had long failed. Across the political spectrum, ingrained throughout very different school systems, says Noguera, is a pervasive and passive acceptance of the "fact" that students from low-income backgrounds cannot achieve at the levels of students from privileged backgrounds. In schools in big and small cities across the country, "there is a culture that allows failure to be accepted over a long period of time," he says. "People are no longer troubled by it."

Which explains why he is at Rindge this morning. The Cambridge school and seven other high schools in Boston are at the center of a year-long study of student achievement. Like Berkeley High, Rindge is integrated racially and socioeconomically. Yet students of color and those from poor families are more likely to drop out, to take non-college-prep courses, to do poorly in the classes they take. "We're looking at school reform from the perspective of the students," is how Noguera puts it. "Where do kids get motivation and resilience? What kinds of relationships lead to higher outcomes? How do kids navigate problems that happen outside of the school? What could schools do to help them with those problems?" He raises questions that the year-long study will attempt to answer--with the results shared and discussed with the practitioners themselves.

Noguera has been to the school several times before. His daughter, Amaya, is a junior there. (Noguera's children learn to live with having their father a continual presence at school. His son, Joaquin, was at Berkeley High when Noguera was working on the Diversity Project.) He also spoke to Cambridge administrators and then to Cambridge teachers at the end of August as part of their professional development. His speech to the teachers brought down the house. "Right when he was coming to the end of his time to speak, two teachers approached me and said, 'Don't let him stop--he's the best person we've had speak to us in 20 years,'" remembers Caroline Hunter, the assistant principal. She sent a note up, giving him more time. When he did finish, there was a long ovation.

"He was very impressive," says Hunter. "It's what we say about people who understand what we do and understand the importance of giving new information and motivation." Often that means telling educators about people in other parts of the country who, with the same population of students, have done something that worked--have established a program involving families directly in the school, or have eliminated tracking successfully--all of which have helped failing students to succeed.

On this October visit, Noguera makes several stops. One is to talk to Deb Socia, the director of School 2, one of five small schools being created out of the large Rindge and Latin. Small schools are seen as more nurturing, as a potential way to break down the segregation of tracking. But Noguera says, "Small schools are necessary, but not sufficient, to help all students to achieve at high standards." There has to be much more. "So much of school reform has been about changing the structure of the schools," he says. "They've missed the whole aspect of the culture of the schools--the expectations they have of the students, the student-teacher relationships, the purposefulness of the whole school."

Socia welcomes him to her office because she is familiar with his work--and she knows Amaya. "The focus on equity is a difficult conversation," she says. The faculty is predominantly white and on average they have been teaching for 28 years. Rindge and Latin educates many upper-middle-class white students and sends them on to prestigious colleges, but 40 percent of its student body lives in housing projects and is predominantly of color. In general, the school has not been as successful with them.

The conversation moves back and forth. The issue has never been lack of ideas or lack of money. "We haven't found the right way to connect with the kids," she says.

"You're right, it's not a question of resources," he answers. He sits with elbows on knees, listening. He doesn't take notes; he doesn't barrage her with questions. He both listens and talks.

Socia talks about how they set up an afterschool tutoring program, but few students have taken advantage of it. Why? She has some ideas but says she thinks his research will tell her more: "We really want the data to help guide our change."

Later, wandering through the halls, Noguera stops to chat with another teacher. Her room is pleasant to walk into, full of light, with student papers hung all around. She has been teaching for exactly 28 years. The discussion, with the two seated at student desks, weaves around to the achievement gap, shorthand for talking about the differences in test scores, grades, and other measures between affluent white students and low-income students of color.

"What I see is not so much race as class," says the teacher. "If students have been read to, talked to, taken on field trips, they'll do well. If they haven't been, then that student is at a disadvantage. How do you make up for it?"

"Are kids pushed enough about academics?" asks Noguera. There is no edge to the question; it is part of their larger conversation.

"It's hard to say...The group helps to motivate. Peers...it's not individual action. If I tell them the assignment is important and if I'm not getting any back-up..." her voice wanders off. "It all comes back to the individual student. Each kid has a story. If they have parents who talk to them, read to them, they tend to do well. If they have parents who are too busy..."

Noguera listens and takes it all in. He is familiar with the song...teachers, even those with the reputation for doing creative things in class, who say that everything is predetermined by the home students come from. "It comes back to what difference you make," he says later, walking back to his office from the school. "What value have you added? What is the school doing? It's easy to teach kids with two parents, who speak English at home. But what about the kids who don't have that?"

That in essence is what Noguera's work has been all about. How can schools serve those students better, instead of seeing their backgrounds as the issue, the thing that immediately explains failure? "Locating the problem in the student," he says, "instead of considering what adults can do to engage kids more in their educational experiences, is exactly what the problem is about."

In a paper he ironically entitled "The Trouble with Black Boys," Noguera discusses the ways in which schools tend to marginalize black boys--by labeling them as behavior problems and less intelligent, punishing them more severely, and excluding them from more rigorous classes. But he deals as well with the notion that many black boys construct their actions and their identities in a way that works against trying to achieve in school, which they identify as "acting white."

"Schools have to carefully examine their own practice, especially in terms of the way they treat and sort black male children," he says in discussing the paper. "When they discipline them, do they punish them or help them? Do they push them into remedial classes or into intellectually challenging ones? Schools also need to work out supportive relationships with community-based organizations and parents to have increased influence on the way kids act." And as he often does, he mentions a program that does just that--the Omega Boys' Club based at the Portero Hills Housing project in San Francisco, which both mentors and tutors boys and takes them on visits to historically black colleges. Boys who know no one who has gone to college, or even graduated from high school, can begin to see other options for themselves as they meet young men from neighborhoods like their own who are navigating successfully as undergraduates.

The paper begins with a personal anecdote. He found himself driving across the Bay Bridge with two other successful, professional black men. Ever the sociologist, Noguera raised the question, "Why are we doing so well when so many other brothers are not?" Each had been raised in working-class families and in tough neighborhoods; each while still young had had close friends and family members killed--and knew others who were serving time in jail. Yes, each had been raised by both parents, but none had regular contact with his father. Noguera goes down a check list, pro and con, back and forth, and ultimately decides that some measure of their success comes down to luck. What can be done to change the "luck," the chance connections and the accidental support mechanisms the three encountered that enabled them to succeed? This is where he sees the powerful role that schools can have.

This is one of the few personal notes in Noguera's writings, but he draws often on what he sees in schools, teachers he has observed, students he has spoken to. He was born in Brooklyn, son of a Venezuelan-Trinidadian housing authority policeman, who had once been a communist and Paul Robeson's bodyguard, and a Jamaican mother, who is a devout Jehovah's Witness. It was arguing with his uncles, he says, who were conservative cops and taxi drivers, that drove him into sociology. He graduated from Brown University and went to Berkeley for graduate school, where his wrote his dissertation on political change in Grenada (which he studied right before the U.S. invasion overthrew the socialist government there).

But it was a job as assistant to the mayor of Berkeley that moved him permanently into the study of education. He was approached by the principal of Berkeley's East Campus Continuation School, a school for students who have failed in other schools, who were coming out of the criminal-justice system--who were in many ways the most difficult kids in the school system. The principal asked him to speak to a young man whom he wanted to run for student-body president. "The kid was clearly a drug dealer," recalls Noguera. "I was taken aback. Why did he want a drug dealer to be student-body president? But then I thought about it--he was smart, articulate, and charming. I was intrigued with what the principal was trying to do."

Noguera taught at and later studied the continuation school for 10 years. "It came naturally," he says now. "My heart was there, my interest was there." His experiences there form one chapter of his forthcoming book, Confronting the Urban: The Limits and Possibilities for Change in America's Inner City Schools, which uses a variety of case studies from schools with similar populations that he has observed, researched, and advised in San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, and Richmond, California. Schools that succeed do so not by ignoring the realities of their students' lives, or using those realities as rationales for why the students can't achieve, but by adapting themselves to deal head-on with the issues while providing pupils with the rigorous intellectual life which is at the heart of any really good school.

Because he knows school culture so well, Noguera has an incisive eye for the ways in which a school helps to foster the problems it claims to be remedying. He points out, for example, that it is those schools that have metal detectors, excessive security, and high numbers of suspensions and expulsions of "problem students" that are the least safe. "The phrase 'fighting violence' might seem to be an oxymoron," he notes dryly. "For those concerned with finding ways to prevent or reduce violence, 'fighting' it might seem the wrong way to describe or engage in the effort to address the problem."

Noguera acknowledges that a feeling of safety and order is necessary for teaching and learning to take place in a school, but at a workshop on student discipline that he ran at one middle school, he diagnosed that many of the teachers' fears of their students came from not really knowing them, or where they came from. When he asked audience members what information they would need if they were invited to teach in a foreign country, they generated a long list of topics: politics, culture, economy, history, geography. But the same situation held true in their own classrooms, he pointed out: they were looking at their students--who came from situations very different from their own--across a chasm of race, ethnicity, class, and life histories. Then he took the teachers on a four-hour tour of the neighborhood in his van, pointing out not only the junkies and the winos on some corners, but also the owner-occupied houses and a thriving business district--aspects of a viable neighborhood. One teacher bridled at the tour, announcing, "I don't need to become an anthropologist to teach." Noguera replied, "Is it possible to be an effective teacher if you don't know your students?"

Even in the schools with the most notorious reputations, he points out, he can always find one class where teachers are inspiring their students and where fear of violence doesn't exist. "Many of these 'exceptional' teachers have to 'cross borders' and negotiate differences of race, class, and experience in order to establish rapport with their students," he writes. "When I have asked students in interviews what makes a particular teacher 'special' and worthy of respect, the students consistently cite three characteristics: firmness, compassion, and an interesting, engaging, and challenging teaching style." It's clearly not the metal detector that makes the difference in student behavior, but the humane environment in that class, and the way in which the teacher really knows and understands her or his students.

Noguera highlights Lowell Middle School in West Oakland, which hired a local grandmother rather than security guards: she greeted students with hugs and admonitions to behave themselves. At Berkeley's East Campus Continuation School, the principal was able to "close" the school at lunchtime, not by putting up a fence but by offering alternatives. The students now operate a campus store that both their peers and their teachers patronize.

Examples like these, which pepper both his writing and his speaking, make Noguera a powerful spokesman for what is possible in schools. "A lot of the work I'm doing with educators is trying to get them to see beyond--see the things we take for granted," he says, talking in his office at Harvard. "Sometimes [audiences] see the folly of what they are doing, sometimes not. I talked to a group of superintendents about discipline: how so many of their policies are ineffective, but they keep them anyway--for example, suspending kids who don't come to school. Sometimes when I say something that makes sense, they say they don't have the power to change it."

|

| A familiar presence, Noguera walks comfortably through the halls in the schools he studies. |

| Photograph by Flint Born |

But because he offers alternatives that have worked at other schools, Noguera often gets his audiences to at least consider possibilities other than the lock-step, lock-down approach. "Rather than depriving kids who are already behind of in-school time," he says, "we can require them to spend more time at school on Saturdays or after school. Community service and service to their school can also be an effective form of punishment. The goal of discipline should be to help kids learn to behave differently. Most administrators agree with that, and the brave ones are willing to try new methods."

During some weeks last fall Noguera gave four or five speeches a week: at a conference of youth workers in Cambridge, at a meeting of community-based organizations in New York City, before principals in Chicago, at the Coalition of Essential Schools conference in Seattle--during which time he fit in a debate with conservative Chester Finn in a teleconference from Boston. In other weeks, he spoke only once or twice. (To do all this and his teaching and research, he gets up at 4 a.m. to write and works with a team of graduate students on his research at the Boston and Cambridge schools.) The requests for him to speak in such different venues suggests there is a hunger to hear someone who can talk thoughtfully about schools in the language of his audiences.

Gloria Ladson-Billings, professor of education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, considers Noguera one of the few people in education who has "melded the community with his scholarship." "Typically a scholar does 'community service' that is like an add-on to his research," she says. "Pedro does the community service not just as an addition to his C.V.; he's intellectually engaging with the community."

For Noguera, the complexity of the education field, the fact that "there is no silver bullet, no single thing that can be fixed," is what makes it interesting. "Our schools reflect all of the promise and the problems of society. And if you change the schools, in a small way you change society--because the results are so tangible in the lives of people...That's why I saw it as such a powerful field to work in."

Jessica Siegel, a freelance writer based in New York City, often writes about education. She taught at a large New York public high school for 10 years.