One hundred years ago, the Macmillan Company published The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains, a novel about an unnamed Wyoming cattleman. The book became one of the first mass-market bestsellers and stands as the defining text for America's most durable herothe cowboy. Its author, Owen Wister, A.B. 1882, LL.B.-A.M. '88, was the unlikeliest of creators for his celebrated book. A cowboy he wasn't.

|

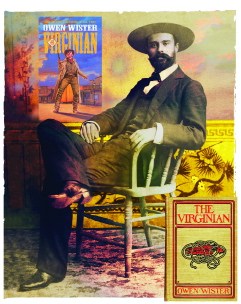

| Covers of a first edition and a 1998 version of The Virginian frame a photograph of Wister taken during a visit to Yellowstone about 1890. |

| Photomontage by Bartek Malysa. Photograph courtesy of American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming (Number 5739). Book cover at lower right courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library. Book cover at upper left courtesy of Forge Publishing. |

Wister was born in Philadelphia, into a gifted family of comfortable means and impeccable social standing: his father was a physician, his mothera daughter of the famous English actress Fanny Kemblea respected magazine writer. Their only child was sent to boarding schools in New England and Switzerland before he entered Harvard in 1878. There he had a brilliant career, earning stellar grades and discovering a talent for musical composition and dramatic writing: in his senior year he supplied both music and libretto for the Hasty Pudding Club's comic opera Dido and Aeneas, which toured professionally in New York and beyond.

Determined to try for a career as a composer, Wister spent the next year studying music in Paris, supported by his dubious father, who disapproved of so unconventional a choice. By 1883, Wister himself had given up. He returned home and eventually took a junior position in a Philadelphia law firm.

If Wister seemed reconciled to legal work, he was also bored and restless. He renewed his interest in fiction, collaborating on a novel with a Harvard friend, and made plans to enter Harvard Law School. Instead he suffered a mysterious breakdown that included vertigo, blinding headaches, and hallucinations. On the advice of his doctor, he traveled west to restore his health. By July 1885, he found himself a guest at the VR Ranch near present-day Douglas, Wyoming. Wister's real life was about to begin.

Wyoming enchanted the polished, cosmopolitan Wister with the stark beauty of its arid plains, its raw, half-civilized newness, and especially its population of profane, whiskey-soaked, pistol-wearing ranch hands, gamblers, stage drivers, and cavalry troopers. In 1891 he began to write stories and sketches of western life and for the next 15 years spent nearly every summer living on ranches, in cow camps, and at cavalry outposts, gathering material. What Wister wrote was fiction, but he didn't make much up, sticking close to events he had heard of or seen. Soon his stories began to be published in Harper's Weekly. Throughout the nineties, the magazine gave him a growing audience and an ambition to write at greater length. He began work on The Virginian in 1901.

The famous novel is a curious book. Wister built it up out of several of his cowboy stories, loosely linked together and inserted into a new narrative of his hero's courtship of the Vermont girl Molly Wood, who has come to Wyoming as a schoolteacher. The love story is of the predictable, sentimental kind his readers expected, but the episodes of ranch and trail life are unique. These passages are essentially elaborate anecdotes in which the Virginian demonstrates his superior skill, wit, and character in feats of horsemanship, practical joking, gunplay, and, most famously, in facing down an enemy ("When you call me that, smile!"). They have a clarity, a realism, that is authoritative from the opening paragraph, and they made The Virginian an immediate sensation. It sold nearly 200,000 copies its first year, and was soon adapted successfully for Broadway by Wister himself. Five movies and at least one TV series have been made since, and the book has never been out of print. In fact, his novel is the template on which every western since has been cut. All the essential characters are to be found there: not only the noble, nameless hero, but also the eastern tenderfoot narrator, the high-spirited, virginal schoolmarm, hostile Indians, cattle rustlers, the shrewd camp cook, the callow kid, the devious, doomed villain. The most remarkable point about The Virginian's influence is how thoroughgoing it has been.

Within six months of the book's publication, its author was one of the best-known writers in the land. The fastidious Wister distrusted his new fame, however. His idea of a novelist was his friend Henry James. The unintelligent approval of the autograph-seeking, semiliterate public was repugnant to him.

Ambivalence about his success was linked to Wister's personal disillusionment with the West. He had believed a new kind of American would be produced by the simplicity and rigor of life there: an honorable, chivalrous, high-minded natural aristocrat not unlike the Virginian. Instead he found his beloved Wyoming increasingly overrun with what he disdainfully regarded as the rabble of an excessive democracy: populist politicians, traveling salesmen, rebellious workers, unassimilated immigrants, and tourists.

Apart from a few late stories, Wister's writing about the West ended with The Virginian. He lived in Philadelphia, writing nonfiction, traveling, even dabbling unsuccessfully in politics, becoming as he grew old less and less tolerant of the crass, egalitarian society around him. Not without rue, he understood that his life's monument was one of that society's cultural foundations. In a way, after The Virginian, there need never have been another western. In a way, there wasn't.

Castle Freeman Jr. is a writer with an interest in American history.