Grenville Lindall Winthrop, A.B. 1886, LL.B. '89, had a passion for beauty. He had financial resources, leisure, and eclectic tastes, and indulged his passion hugely. Yet, from what one may know of him, he seems in certain aspects of his life a pathetic figure.

When Winthrop died in 1943, he left his art collection to Harvard. It was vast: about 4,000 objects. By the middle of the 1920s, his treasures had grown so numerous that his capacious house in the Murray Hill neighborhood of Manhattan could no longer accommodate them, and so he built them a new home, on a double lot at 15 East 81st Street, near the Metropolitan Museum. He put the Winthrop crest above the door, for he was proud of his ancestry. (Born in 1864, he was the second son in the ninth generation of an unbroken line of Winthrop men stretching back to John Winthrop, first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.) Inside his new quarters, a veritable museum, he had a bedroom for himself, one guest room, and chamber after chamber full of obsessively arranged objects: early Wedgwood, Pre-Raphaelite paintings, Mesoamerican masks, gold-ground Italian paintings, French drawings, clocks, Korean Buddhas.

Winthrop had amassed "one of the most important, yet least well known, collections ever assembled in the United States," says Stephan S. Wolohojian, Ph.D. '94, associate curator of paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts at Harvard's Fogg Art Museum. It was encyclopedic in scope, yet had focused strengths. Winthrop had gathered in more works by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres than any other private collector. He had a room full of more than 50 works by the painter-poet William Blake. "To this day," according to Wolohojian, "no other collector has been able to assemble a comparable collection of ancient Chinese jades and bronzes." Winthrop's bequest remains the largest single gift of its kind to any university. It had a transformative effect on the Fogg and on teaching and learning about art at Harvard.

Extremely protective of his beauties, Winthrop never loaned them; the University Art Museums have maintained that policy. Harvard has never exhibited the collection as a whole; thus, its depth has continued to be hidden, except from specialists. While many Winthrop objects have been published, and may even have the look of familiarity, the public has not been able heretofore to stand face to face with these masterworks en masse.

Now, an exhibition, A Private Passion, featuring nineteenth-century Western paintings and drawings from the Winthrop collection, organized by Harvard and curated by Wolohojian, opens at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon, in March; at the National Gallery, London, in June; at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, in October; and at the National Gallery, Washington, D.C., in February 2004. It includes works by Blake, Burne-Jones, Daumier, David, van Gogh, Homer, Ingres, Renoir, Rodin, Sargent, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Whistlera dazzling sample of Winthrop's collections in this area. A second Winthrop exhibition, of ancient Chinese art, will rendezvous with the first at the National Gallery in February 2004 and go on to tour internationally.

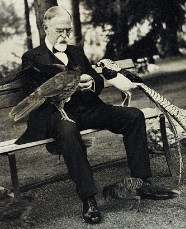

|

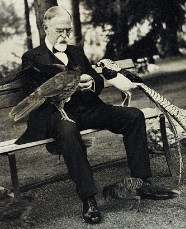

| Grenville Winthrop feeding his pheasants at Groton Place, his summer home in Lenox, Massachusetts. |

Shy, reclusive, solitary, straitlaced, reserved, puritanical, fastidious, aloof, grave, stubborn, stiff, disaffected, "He shielded himself behind a screen of perfect manners." These are some of the adjectives Wolohojian employs in a biographical essay about Winthrop in the exhibition catalog. "He had nice tastes, certainly," Edith Wharton, a close friend of Winthrop's mother, wrote of him, "but he seems to me to want digging out & airing...."

At Harvard, Winthrop studied geology and art history and was a member of the Porcellian Club. He stayed on in Cambridge to get a law degree, and then returned home to New York City and set up a law practice with two others. In 1892, at 28, he married Mary Tallmadge Trevor. They had two girls, Emily and Kate. "Winthrop was ill suited to being a lawyer," writes Wolohojian, "and his practice soon failed. Having limited interest in pursuing another profession, and perhaps even work itself, he retired completely in 1896...."

His marriage was less than successful. Perhaps suffering from postpartum depression, in the spring of 1900 Mary left New York City for her family home in Yonkers; she died suddenly in December. Suicide was speculated. The girls, seven and not quite one, were left in Winthrop's care. Determined to keep them from their mother's emotional fate, he sought expert advice, put them (and himself) on a vegetarian diet, and, to keep them from being overstimulated, had them taught at home. Later, when they were young adults and vacationed at his siblings' houses, he insisted on knowing in advance the names of all the people they would meet. Winthrop had a summer house on 150 acres in Lenox, Massachusetts, where he bought large tracts of nearby Bald Head Mountain to protect his vistas and where, it was said, he had 40 men to mow the lawns and kept 500 peacocks and pheasants to provide a kaleidoscope of color as they roamed the property. Winthrop spent his days either there or in his Manhattan house. In September 1924, when he left Lenox for an overnight trip to New York, both daughters eloped: Emily, 31, with her chauffeur; Kate, 24, with her father's electrician. The New York Times put the story on its front page. Shocked, abandoned, alone, Winthrop turned entirely to collecting art.

He had no love for the hunt andexcept in the case of his Asian art, which he acquired largely on his own, relying on his own discernmenthe depended on trusted agents, with consultation, to discover, buy, and send his treasures to him. One such person, who became a friend, was Martin Birnbaum. "A lawyer by training, an art dealer by vocation, and a violinist at heart," writes Wolohojian, "Birnbaum was as colorful as Winthrop was drab." In his 1960 autobiography, Birnbaum imagined the elderly Winthrop at home: "After a lonely dinner, chiefly of fruit and vegetables, he would read some favorite book, or work on a card catalogue of his treasures....Proust could have done the scene justice. The quiet cork-lined rooms [were] disturbed only by the chimes of the fine collection of grandfather clocks that stood in the rooms, hallways and on most of the landings. They were carefully adjusted so that their mellow bells reverberated successively without interfering with one another, and while their delicate peals vibrated through the house the master would move about the shadows hanging his drawings or cataloguing them, or rearranging the Chinese jades and gilt bronzes."

The following images appear

courtesy of the Fogg Art Museum,

Harvard University Art Museums,

Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop.

©President and Fellows of Harvard College

|

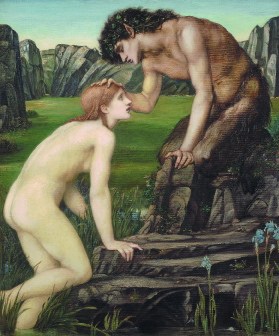

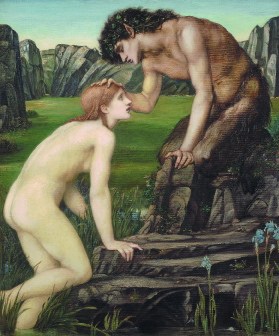

| Pan and Psyche, 1872-1874, by Edward Burne-Jones |

|

| Spring Bouquet, 1866, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir |

|

| The Sirens, 1882, by Gustave Moreau |

|

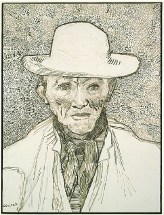

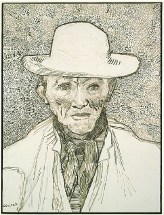

| Peasant of the Camargue, 1888, Vincent Van Gogh |

|

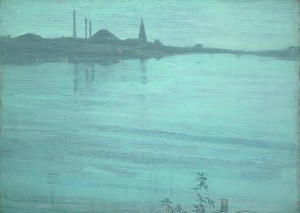

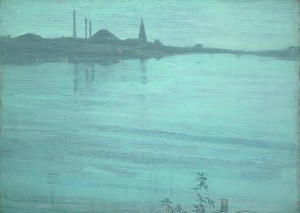

| Nocturne in Blue and Silver, c. 1871-1872, by James McNeill Whistler |

|

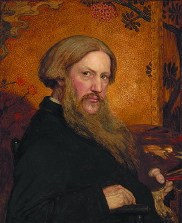

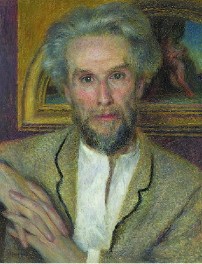

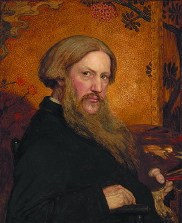

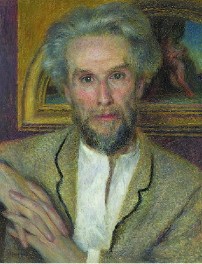

| Self-Portrait, 1877, by Ford Madox Brown |

|

| Eternal Spring, 1884, by Auguste Rodin |

|

| Cain Fleeing from the Wrath of God (The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve), c. 1805-1809, by William Blake |

|

| The Bather, 1808, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres |

|

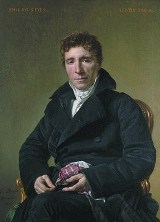

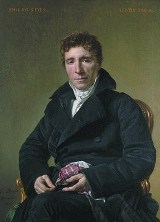

| Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes, 1817, by Jacques-Louis David |

|

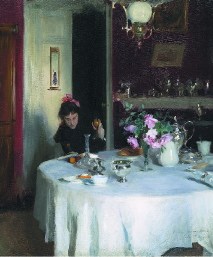

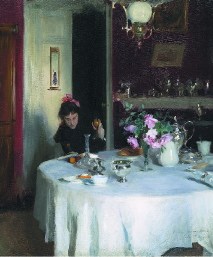

| The Breakfast Table, 1883-1884, by John Singer Sargent |

|

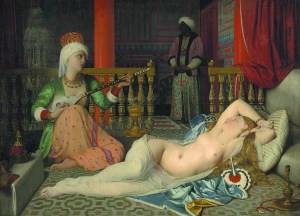

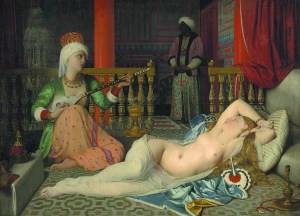

| Odalisque with a Slave, 1839-1840, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres |

|

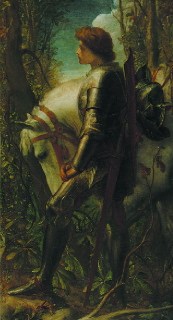

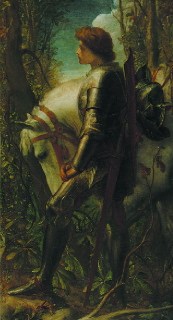

| Galahad, 1862, by George Frederick Watts |

|

| La Donna della Finestra, 1879, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

|

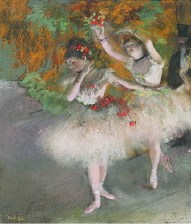

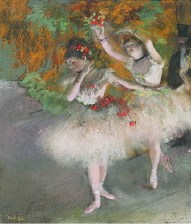

| Two Dancers Entering the Stage, c. 1877-1878, by Edgar Degas |

|

| Road toward the Farm, Saint-Simeon, Honfleur, c. 1867, by Claude Monet |

|

| Victor Choquet, c. 1875, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir |

|

| The White Horse Tavern, 1821-1822, by Theodore Gericault |

|

| Il Ramoscello (The Twig), 1865, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti |

Images courtesy of the Fogg Art Museum,

Harvard University Art Museums,

Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop.

©President and Fellows of Harvard College